In 1999, for the first time, the Surgeon General issued a Call To Action To Prevent Suicide, defining it as a "public health hazard." In public interviews he noted how in 1998 for every two homicides in the U.S. there were three suicides. Since 1952, the incidence for adolescents and young adults has nearly tripled, and 90% of these cases were due to guns. Each day 86 Americans take their own lives and another 1,500 attempt to do so.

Two years later, President Bush's new Surgeon General, Dr. David Satcher, repeated the alarm and unveiled a national blueprint to challenge "a preventable problem.

No one really knows why people commit suicide and perhaps the

person least aware is the victim at the moment of the decision. An

estimated 2.9%

of the adult population attempts suicide. In efforts

to explain this 8th-leading

cause of death (third for Americans 15-24), scientists have located the cause of

self-destructive behavior both within and without the individual. Physiologists,

for instance, have found those with low serotonin (5-hydroxyindoleacetic

acid) levels to be as much as ten times more likely to be victims than

those with higher amounts. Psychologists talk of precipitators in terms

of personality disorders, feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, and alienation,

and uncontrollable urges to shed an unwanted self (see,

for example, Pierre Tremblay's "The Homosexuality Factor in the Youth

Suicide Problem").

The very field of sociology was in part founded on the discovery that suicide rates are as much a sociological phenomenon as they are psychological. Around the turn of the century, French sociologist Emile Durkheim found that single people were more likely to be victims than married individuals, Protestants more likely than Catholics, urban residents more likely than rural folks. Arguing that suicide was related to the nature of the bonds between self and society, Durkheim argued that either excessive or deficient levels of integration and regulation lead to four "ideal types" of suicide:

To see this social variability of suicide, click here to see the 2001 state rates. Across the United States there is a four-fold difference in rates, ranging from New Mexico (19.8 suicides per 100,000 population) and Montana (19.3) to New York (6.6) and Massachusetts (6.7). Among the major predictors: 1998 divorce rates (r=.75), the percent of the population having no religious affiliation (r=.41), 1995 fatal accident rates (.59), and the percent of the state comprised of Catholics (r=-.40).

Turning to international rates, consider the following table from The Statistical Abstract of the United States 1982-83 (for more recent rates see WHO's country reports), where rates are broken down by age and sex:

| MALE RATES (per 100K) | FEMALE RATES (per 100K) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COUNTRY | 15-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 65+ | 15-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 65+ | TOTAL | |||

| Austria | 28.8 | 40.0 | 58.1 | 77.2 | 6.7 | 12.7 | 21.8 | 31.1 | 35.5 | |||

| Switzerland | 31.0 | 39.2 | 50.6 | 59.4 | 13.2 | 16.3 | 24.3 | 22.2 | 32.5 | |||

| Denmark | 16.3 | 51.4 | 71.2 | 67.7 | 7.7 | 25.5 | 41.1 | 32.4 | 29.9 | |||

| W.Germany | 19.0 | 30.1 | 40.8 | 60.4 | 5.6 | 12.1 | 22.0 | 26.6 | 27.8 | |||

| Sweden | 16.9 | 35.3 | 39.4 | 42.7 | 5.8 | 13.6 | 19.6 | 13.2 | 27.7 | |||

| France | 14.0 | 25.5 | 36.2 | 62.3 | 5.2 | 9.1 | 14.9 | 21.3 | 22.9 | |||

| Japan | 16.6 | 26.8 | 32.9 | 51.3 | 8.2 | 11.9 | 16.3 | 44.4 | 21.4 | |||

| Poland | 19.5 | 31.8 | 34.9 | 24.7 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 19.3 | |||

| USA | 20.0 | 24.0 | 25.3 | 38.0 | 4.7 | 8.9 | 10.5 | 7.4 | 18.9 | |||

| Canada | 27.8 | 30.3 | 30.2 | 28.6 | 5.7 | 10.1 | 12.8 | 8.7 | 17.2 | |||

| Australia | 17.6 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 25.3 | 4.5 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 15.2 | |||

| Norway | 20.4 | 19.2 | 30.3 | 25.0 | 3.3 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 7.5 | 14.2 | |||

| Netherlands | 6.2 | 13.4 | 20.7 | 27.8 | 2.7 | 9.8 | 17.7 | 18.0 | 10.8 | |||

| Israel | 10.8 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 23.4 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 15.9 | 9.6 | |||

| UK | 6.4 | 14.1 | 16.6 | 19.3 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 11.4 | 12.3 | 9.1 | |||

| Ireland | 6.2 | 11.1 | 12.1 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 8.4 | 3.6 | 6.6 | |||

In this sample of basically European countries, observe in the right-most column that there is a five-fold difference in suicide rates between Austria and Ireland. For all age categories, male rates exceed female rates. In eleven of our sixteen countries male rates are highest in old age, while such is the case for females in only seven.

Any analyses of such data must be taken with extreme caution. Undoubtedly there are national differences in the reporting and classification of deaths as suicide and these differences, in turn, probably vary by the sex and age of the deceased. In the United States, for example, suicides of older individuals are more frequently recorded as being due to "natural causes" than is the case for other age groups. With this qualification in mind, let's see what stories might be revealed in this data. First, let us divide female rates by males for each age category. Observe, for instance, that young Austrian women commit suicide at a rate that is 23% that of young Austrian males and that this ratio nearly doubles among Austrians 65 years of age and older:

NATIONAL RATIOS BY AGE OF FEMALE/MALE SUICIDE RATES

| COUNTRY | 15-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 65+ |

| Austria | .23 | .32 | .38 | .40 |

| Switzerland | .43 | .42 | .48 | .37 |

| Denmark | .47 | .36 | .58 | .48 |

| W. Germany | .29 | .40 | .54 | .44 |

| Sweden | .34 | .39 | .50 | .31 |

| France | .37 | .36 | .41 | .34 |

| Japan | .49 | .44 | .50 | .87 |

| Poland | .22 | .14 | .18 | .23 |

| USA | .23 | .37 | .42 | .19 |

| Canada | .21 | .33 | .42 | .30 |

| Australia | .26 | .35 | .37 | .31 |

| Norway | .16 | .42 | .43 | .30 |

| Netherlands | .43 | .73 | .86 | .65 |

| Israel | .11 | .46 | .51 | .68 |

| UK | .47 | .43 | .69 | .64 |

| Ireland | .40 | .43 | .69 | .84 |

So what inferences are you willing to make about gender differences in the challenges of the life course? In Israel, that Durkheimian bond between self and society certainly appears to be more challenging for young males than for young females, where the ratio of female to male suicide rates is but one-quarter that of Japan and Denmark. And, relative to females, old age appears to be considerably more satisfying to elderly Japanese and Irish males than it is in the United States.

Another way to consider the relative challenges of the life

course is to standardize the rates for male and female suicides for those

15-24, 25-44, and 45-64 in terms of their suicide rates in old age. In

the table below we find, for instance, that the suicide rate of young Austrian

males is 37% that of elderly Austrian males while the suicide rate of young

Austrian females is but 22% that of elderly Austrian females:

| MALE STD. RATES | FEMALE STD. RATES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COUNTRY | 15-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 15-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | |

| Austria | .37 | .52 | .75 | .22 | .41 | .70 | |

| Switzerland | .52 | .66 | .85 | .59 | .73 | 1.09 | |

| Denmark | .24 | .76 | 1.05 | .24 | .79 | 1.27 | |

| W.Germany | .31 | .50 | .68 | .21 | .45 | .83 | |

| Sweden | .40 | .83 | .92 | .44 | 1.03 | 1.48 | |

| France | .22 | .41 | .58 | .24 | .43 | .70 | |

| Japan | .32 | .52 | .64 | .18 | .27 | .37 | |

| Poland | .79 | 1.29 | 1.41 | .74 | .79 | 1.09 | |

| USA | .53 | .63 | .67 | .64 | 1.20 | 1.42 | |

| Canada | .97 | 1.06 | 1.06 | .66 | 1.16 | 1.47 | |

| Australia | .70 | .91 | .91 | .57 | 1.03 | 1.09 | |

| Norway | .82 | .77 | 1.21 | .44 | 1.07 | 1.73 | |

| Netherlands | .22 | .48 | .74 | .15 | .54 | .98 | |

| Israel | .46 | .40 | .55 | .07 | .27 | .42 | |

| UK | .33 | .73 | .86 | .24 | .48 | .93 | |

| Ireland | 1.44 | 2.58 | 2.81 | .69 | 1.33 | 2.33 | |

In what countries would you find the challenges of midlife to be considerably greater than those of early adulthood and old age--if you are a male? a female?

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services ("Suicide

Among Older Persons, United States, 1980-92, MMWR

[Jan. 12, 1996]), age-specific rates of Americans suicides have consistently

been highest among older

persons. Though accounting for 13% of the populations,

older Americans commit nearly one-fifth of all suicides. Though the overall

suicide rate for persons 65 and older had been declining from the 1940s

through the 1980s, it increased in the late 1980s before once again declining

throughout the 1990s. Why the suicide rate of elderly black Americans is

but a fraction of that of their white counterparts has intrigued workers.

According to a 2002 study by Joan Cook and her colleagues (in the August

special suicide issue of The

American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry), the answer may lie in the

strong religious faith and social support of African Americans.

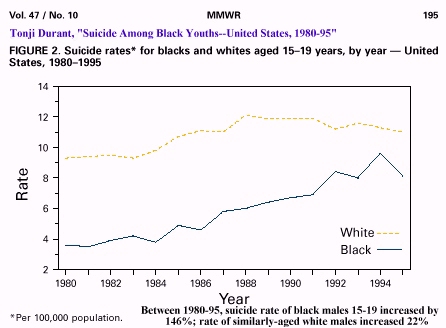

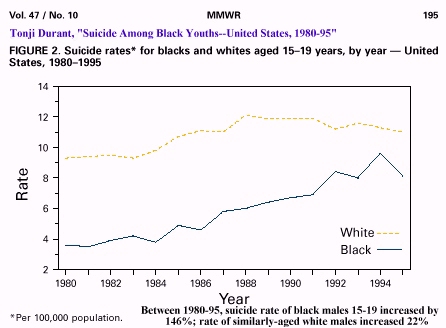

Concurrently, the rate of suicide

among young adolescents increased 120% from 1980 to 1992. Once extremely

rare among teenagers, suicide has become the third-ranking cause of their

deaths, after accidents and homicides.

Click here to see

In the United States, in the wake of stories of the right-to-die, Jack Kevorkian, and suicide pacts of elderly couples, the morality of the terminally ill to take their own lives has become a matter of considerable discourse. Since 1977, the National Opinion Research Center has included the following question in its General Social Surveys: "Do you think a person has the right to end his or her own life if this person has an incurable disease?" In 1994, 61% of American adults agreed with this statement compared to 38% seventeen years earlier.

Click to see

This chart is worth considering

in light of the actual suicide rates of these groups:

AGE-ADJUSTED

SUICIDE RATES (PER 100,000)

BY RACE AND SEX IN 1991

| MALE | FEMALE | |

| WHITES | 19.9 | 4.8 |

| BLACKS | 12.5 | 1.9 |

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1993. Monthly Vital Statistics, vol. 42(2), Tables 10-11 (Aug. 31):38-41.

So what is the bottom line in understanding why people take their own lives? The 1996 suicide (due to overdose of sedatives) of Margaux Hemingway brought the memories of her grandfather, who committed suicide, as did his brother, sister and father. Is the answer genetic? Do, for instance, people inherit a proclivity toward profound depression which, in turn, predisposes them to be more likely to commit suicide? Or does the Hemingway family story rather indicate an intergenerational socialization pattern where committing suicide when depressed is an acceptable "family way" of addressing the problem? Is the answer purely psychological? Let's say for sake of argument that certain personality types are significantly more predisposed. However, historical and anthropological studies show how different cultures seem to produce distinctive spectrums of personality types and that modal types can change over time. In other words, the proportion of suicide-prone persons in a population is socio-culturally determined. Further, changing social conditions can either trigger or suppress the suicidal urge of these types of selves:

Bottom line: suicide is a highly complex phenomenon that involves the interactions between genetic, biochemical, psychological, societal, and cultural factors.

Suicide Resources on the Web

![]()