POLITICS OF AGING:

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND THE AGING NETWORK

The new class war between the young and the old will manifest itself

in several ways. First, there will be heavy pension taxes that may eventually

absorb more than one-fourth of the income of both workers and employers.

This new class war may progress so far that we will see workers and employers

standing shoulder to shoulder against the hard- driven politicians who

promise our senior citizens impossible pensions and encourage the older

worker to exploit the younger worker, the older farmer to exploit the younger

farmer, the older businessman ..., the older professional man ... Let us

remember that these pension leaders will soon have the votes. Karl Marx

and others have taught us that mass movements are rarely rational: they

spring from broad social changes. These basic changes in the population

pattern started recently and slowly; the resulting mass movement has not

yet matured. Townsendism may be as

important in the next fifty years as

were the doctrines of Karl Marx during the last half century.

--F.G. Dickinson, in report to the

First Annual Southern

Conference on Gerontology, 1951

Has Dickinson's prophecy come to be? In Jagadeesh Gokhale and Laurence Kotlikoff's

"Is War Between

Generations Inevitable" they note how in 2001 a 65-year-old female can expect to receive $163,000 more in

government transfer payments (e.g., Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other state and federal welfare

entitlements) than she will pay in taxes. A 20-year-old female, on the other hand, can expect

to pay $92,000 more in taxes. Further, these two practitioners of the new

discipline of "generational accounting" observe that while "an

American born today can expect to pay 17.7 percent of his or her income over and

above any transfer benefits he will receive," tomorrow's newborn can expect

to pay 35.8%.

Former British Minister of Health, Ian Macleod, wrote that "in

the capitalist democracies, the ageing of the population has raised new

difficulties. It is the `Mount Everest' of the present day social problems."

"Not only are there many more aged people than there were," wrote

Simone de Beauvoir in The Coming of Age, "but they no longer spontaneously integrate with

the community: society is compelled to decide upon their status, and the

decision can only be taken at the government level. Old age has become

the object of policy."

Former British Minister of Health, Ian Macleod, wrote that "in

the capitalist democracies, the ageing of the population has raised new

difficulties. It is the `Mount Everest' of the present day social problems."

"Not only are there many more aged people than there were," wrote

Simone de Beauvoir in The Coming of Age, "but they no longer spontaneously integrate with

the community: society is compelled to decide upon their status, and the

decision can only be taken at the government level. Old age has become

the object of policy."

Consider what is, in effect, the Bill of Rights for the Old, Title

I of the 1965 Older

Americans Act:

- An adequate income in retirement in accordance with the American

standard of living.

- The best possible physical and mental health which science can make

available and without regard to economic status.

- Suitable housing, independently selected, designed and located with

reference to special needs and available at costs which older citizens

can afford.

- Full restorative services for those who require institutional care.

- Opportunity for employment with no discriminatory personnel practices

because of age.

- Retirement in health, honor, and dignity--after years of contribution

to the economy.

- Pursuit of meaningful activity within the widest range of civic,

cultural, and recreational opportunities.

- Efficient community services which provide social assistance in

a coordinated manner and which are readily available when needed.

- Immediate benefit from proven research knowledge which can sustain

and improve health and happiness.

- Freedom, independence, and the free exercise of individual initiative

in planning, and managing their own lives.

(U.S. Annotated Code, Title 42)

Do you know of any other age groups with such entitlements?! Whereas

in 1992 some 46% of all federal domestic spending went to the elderly,

only 11% went to children. Click here to examine this

share of federal expenditures going to older Americans in 1995. In

2001, 6.7% of America's GDP went to Social Security and Medicare (at a time when

government spending was about 20%); projections are that in 2030 this will rise

to 11.1%. Among the

consequences of

this legislation was the creation of the "aging network," including

state agencies on aging and

area agencies on aging, the abolition of most

mandatory retirement age limits, meals-on-wheels, and numerous oversight and referral

services. Click here for the 2006 Amendments to the Older Americans Act.

Over the past quarter century, as the proportion of older persons

living in poverty has declined, that of children has increased. Click here

to see longitudinal poverty rates of the young and

old. See also "Living Younger

Longer" from the 2005 White House Conference on Aging (Oct. 1, 2004).

- Robert

Hudson's "Political Science Perspectives on Aging Policy"

THE VOTING CLOUT OF OLDER

AMERICANS

Americans over 60 years of age vote with a vengeance and constitute a formidable

bloc (see Casey Mulligan & Xavier Sali-i-Martin's "Gerontocracy,

Retirement, and Social Security" [pdf format]). They have a vested

interest in the political allocations: in 2002, Social Security and Medicare had

roughly 40 million beneficiaries. According to the New York Times's "Portrait of the 1996 Electorate," those sixty and older

cast 24 percent of the total vote. This political clout will only increase as more educated

cohorts enter into their sixties and seventies. In 1986, according to the Census Bureau, for the

first time since 18-year-olds won the right to vote in 1972, America's youngest voters (those

18-24) were outnumbered by the elderly. Ten years later, those 18 to 29 cast but 17 percent of

the total vote.

PERCENT HAVING VOTED (IF WAS ELIGIBLE TO DO SO)

IN LAST PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

BY AGE AND EDUCATION (COMBINED 1973-94 NORC GSS)

|

0-11 YRS |

HS GRAD |

SOME POST-

SECONDARY |

4+ YEARS

COLLEGE |

TOTAL |

| 18-29 |

22 |

42 |

62 |

74 |

51% |

| 30-39 |

38 |

61 |

73 |

85 |

66% |

| 40-49 |

53 |

74 |

82 |

91 |

75% |

| 50-59 |

64 |

83 |

89 |

94 |

80% |

| 60-69 |

69 |

87 |

90 |

95 |

81% |

| 70-79 |

74 |

88 |

91 |

93 |

81% |

| 80+ |

70 |

83 |

87 |

95 |

77% |

| TOTAL |

58% |

68% |

76% |

86% |

|

So can older voters really be perceived as a voting bloc? Only if matters directly

affect them. You will note from the New York

Times's "Portrait of the 1996 Electorate" that older persons' votes generally have

over the past seven Presidential elections been distributed among candidates in about the same

proportions as have those of middle-aged and younger persons. The notable exceptions were in

1988, when they were significantly more likely than others to go for Dukakis, and in 1992,

when they were significantly less likely to vote for Perot.

Will age- or generationally-based politics ultimately replace in the 21st

century the race- and ethnically-based politics of the 20th? Given the

immigration wave of the 1980s and 1990s, it may well be the case that

age-dynamics will only amplify the politics of the past, especially as the old

will be disproportionately Anglo and the young will be disproportionately

comprised of Hispanic and Asian Americans. For one prognostication of the

forthcoming impacts of aging Boomers on the political order see Peter Keating's

"Wake-Up

Call" (AARP: The Magazine, September & October, 2004).

FEDERAL SERVICES AND RESOURCES

- Administration on

Aging

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging

- The National Aging Information

Center

- National Association of Area Agencies on Aging

- National Institute on Aging

- FirstGov for Seniors

- Jacob Siegel's

"Aging Into the 21st Century" (AoA Report, 1996)

- Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

Home Page

- Final Report

of the 1995 White House Conference on Aging

SOCIAL SECURITY

There can be little doubt, in light of the President's State of the Union

Address and the debate that it has generated, that Social Security will be one

of the hot political issues of 2005. One decade earlier, Social Security constituted 22 percent of federal spending,

about 46 percent of all of its domestic spending. This program takes more

money out of Americans' paychecks than does the federal income tax for

nearly four out of ten American taxpayers (Click here to see how maximum

taxable earnings and tax rates have changed since 1937). It is a regressive tax. (Made

over $200,000 last year? Lucky you! You only have have to pay Social Security

taxes on $87,900.) As will be developed below, built into the program is a system of

"generational inequity,"

which has been likened to a huge Ponzi or pyramid scheme with

payoffs proportional to how early individuals entered the game. It also has built-in class and

racial inequities: life expectancy of the black male is barely more than the "magic

age" of 65 at which time males can now retire with full benefits.

The first national social security program was implemented in 1883

by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who, we should note, established

that "magic age" of 65 at a time when life expectancy at birth

was about 37 years. Bismarck's motivations were not so much humanitarian

but politically motivated: the masses had to be weaned away from socialism,

just as was the case sixty years later when FDR penned this country's program

into law (see the SSA's version of

its own history here). When Social Security began, only 54% of all men

and 62% of all woman lived until 65; those who did make it that far could

expect to live another 12.8 years. By 1990, 72% of all men and 84% of all

women could expect to live until 65, and those who live that age in 1982

could expect to live more than 16 years.

Of all federal programs, Social Security has had an undeniable effect

on the poverty rate of the oldest segment of the population. The poverty

rate for those sixty-five and older fell from 35 percent in 1959 to 25

percent in 1970 to a 1989 low point of 11 percent. Demographics contributed to the success of

this program that redistributes income from younger to older generations--and will contribute to

its demise: in 1950, there were 16.5 workers per each beneficiary; by 1990, this ratio had

declined to 3.3. By 2020, when most boomers will have entered into their seventies and eights,

this ratio has been projected to be about 2.4.

Indeed, for early cohorts of older Americans, Social Security proved to be a great

deal. Take, for instance, the case of Ms. Ida Fuller, recipient of the nation's first Social

Security check, numbered 00-000-001, in 1940. She lived to the ripe old age of 100 and, for

her $24.75 contribution in employee taxes, collected for than $20,000 in benefits. In

Borrowed Time, Peter G. Peterson and Neil Howe describe how a man born in

1916, who began working at age 21, and who earned the average wages in Social Security-

covered employment throughout his career. He retires in 1981 at age 65, and with his 65-year-

old nonworking wife will receive, assuming average life-expectancy, some $178,000 in Social

Security and Health Insurance. Still not a bad return on the $39,000 he paid in payroll taxes!

The authors go on to note how this couple would have been reimbursed for all their Social

Security payments plus interest within their first three and one-half years of retirement, and

how, after six and one-half years, they would have been reimbursed for all of their federal

income taxes as well. But such returns are not in the cards for the post-war generations. In the

mid-nineties, an often-reported statistic was how

more young Americans believed in UFOs than

in the likelihood of their receiving Social Security when they retire.

According to George Church and Richard Lacayo ("Social

(In)Security,"

Time, March 20, 1995:24-32):

- In 1995, a time when those numerous Boomers were hitting their earnings peak,

SSA ended up with a surplus of $58 billion.

- This surplus goes into a trust fund (contrary to what 15%

of Americans believe, it doesn't go into personal accounts) where it is

"invested" in Treasury bonds.

- This "investment" is actually an IOU of the federal government,

which spent this $58 billion on such things as military weapons and welfare

checks.

- Check out the bookkeeping: "The government gets to report a

deficit of $193 billion, rather than the $251 billion it would have to

confess to if it did not have the use of that Social Security money. At

the same time, the Social Security trust fund shows an increase of $58

billion in the money it supposedly has stashed away to pay future pensions."

- When the crunch comes and money paid out exceeds that which is taken

in, the Treasury bonds must be converted to cover payments. To do this

the federal government has several grim choices: raise federal taxes, raise

Social Security taxes (which have already been raised ten-fold over the

past 45 years), slash pensions, or just print more currency (how do you

spell I-N-F-L-A-T-I-O-N?)

And how do Americans view this program and its effect on aged poverty?

According to The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard

University Survey Project's "Why Don't Americans Trust the Government?"

survey of late 1995 (n=1,514 adults 18 and older), when asked "Compared

with 20 years ago, do you think the share of Americans over 65 who live

in poverty has increased, decreased or stayed about the same?" some 59%

believed that it had increased (and only 15% saw a decrease). And when asked about

"what effect, if any, do you think the federal government's [old age] programs have had

on the share of Americans over 65 who live in poverty", only 23 percent thought that

they have "helped make things better" while 32 percent thought they have

"made things worse" and 39 percent seeing not "much effect either

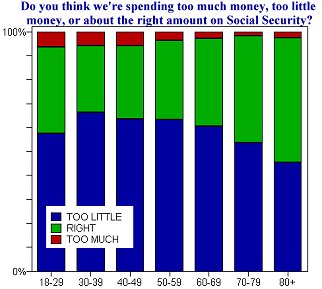

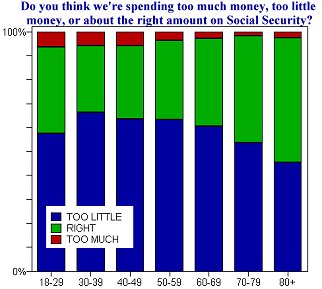

way." According to the combined 2000-2002 NORC General Social Surveys of American adults

(n=5,297), as can be seen in the graph on the right, belief that we're spending too little on Social

Security generally decreases with age, from 66% of those in their thirties to

45% of those eighty and older.

And how do Americans view this program and its effect on aged poverty?

According to The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard

University Survey Project's "Why Don't Americans Trust the Government?"

survey of late 1995 (n=1,514 adults 18 and older), when asked "Compared

with 20 years ago, do you think the share of Americans over 65 who live

in poverty has increased, decreased or stayed about the same?" some 59%

believed that it had increased (and only 15% saw a decrease). And when asked about

"what effect, if any, do you think the federal government's [old age] programs have had

on the share of Americans over 65 who live in poverty", only 23 percent thought that

they have "helped make things better" while 32 percent thought they have

"made things worse" and 39 percent seeing not "much effect either

way." According to the combined 2000-2002 NORC General Social Surveys of American adults

(n=5,297), as can be seen in the graph on the right, belief that we're spending too little on Social

Security generally decreases with age, from 66% of those in their thirties to

45% of those eighty and older.

With this level of pluralistic ignorance (which may well have kept a number of

generationally-based social movements from sprouting), reform will be difficult as time begins

running out. According to the Cato

Institute, sometime between 2006 and 2012 Social Security will begin paying out more

than it takes in. In fact, the event transpired in 2010 in the midst of the Great Recession. Among the options being considered is the privatization of the program, with

the Chilean pension system often pointed

to as a model to be emulated. There all but the poorest tenth of workers are required to

put 12% of their salaries into one of twenty-four government-regulated investment funds. With

national savings rate up to 29% (compared to 3% in the United States), that nation's economy

is prospering as are its citizens, whose average net worth is roughly four times their average

salary (compared to a ratio of one in the U.S.). Be sure to check out the positions

favoring and opposing privatization among the groups below.

- "Social Security 75th Anniversary Survey Report: Public Opinion Trends" (2010)

- SSA Home Page, including the

2004 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal

Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds, which claims the trust fund will remain solvent until 2038

- Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities' "How Would Various Social Security Reform Plans Affect Social Security

Benefits? An Analysis of the Congressional Research Service Report"

- Century Foundation's Social Security Network

- Public Agenda's Social Security Study Guide

- Christiane

Roehler's "The Social Security Page"

- Walter M. Cadette, "Social Security Privatization: A Bad Idea" (Policy Notes from the Jerome Levy Economics Institute)

- Christian E.

Weller, "Raising the Retirement Age: The Wrong Direction

for Social Security" (Fall, 2000)

- PizzaEconomics claims that

"privatizers are feeding the American public a lot of misinformation about Social

Security"

- C. Eugene Steurele's

(Urban Institute) "The Simple Arithmetic Driving Social Security Reform"

INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL SECURITY PROGRAMS AND

INITIATIVES

- Social Security

Programs Throughout the World-1997 (pdf format)

- Japan's

Social Security Initiatives (from Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

- International Labour

Organization's Cost of Social Security--Basic International Tables, 1990-93

MEDICARE/MEDICAID

Throughout the 1990s, escalating medical costs for older persons sent political

shockwaves throughout Washington. Between 1990 and 1997, Medicare spending had

increased an average of 10% a year. Any threats of spending curtailments

quickly produced powerful opposing social movements. The

Spring of 1993, for instance, saw a group of 20 organizations representing the aged, hospitals and physicians

launch an attack on rumored Senate cuts of as much as $35 billion in Medicare and Medicaid

spending. The House had approved $55 billion in cuts in future Medicare and Medicaid spendings, which over the following five years was projected to be $1.1 trillion just for

Medicare. By the conclusion of the fiscal year ending September 30, 1998, annual

Medicare spending had reached $212 billion. Six years later it was almost

$300 billion.

Throughout the 1990s, escalating medical costs for older persons sent political

shockwaves throughout Washington. Between 1990 and 1997, Medicare spending had

increased an average of 10% a year. Any threats of spending curtailments

quickly produced powerful opposing social movements. The

Spring of 1993, for instance, saw a group of 20 organizations representing the aged, hospitals and physicians

launch an attack on rumored Senate cuts of as much as $35 billion in Medicare and Medicaid

spending. The House had approved $55 billion in cuts in future Medicare and Medicaid spendings, which over the following five years was projected to be $1.1 trillion just for

Medicare. By the conclusion of the fiscal year ending September 30, 1998, annual

Medicare spending had reached $212 billion. Six years later it was almost

$300 billion.

Not surprisingly, such sums triggered considerable greed. During the 1980s there were reports of

Medicare and Medicaid being billed for patients never seen, for excessive tests, and for

prescriptions never filled. In 1989, a government study by

Richard Kusserow, the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services,

found that physicians who own or invest in laboratories prescribed 45% more clinical services

for Medicare patients than did other physicians. Also that year the GAO concluded that over

$10 billion in Medicare funds had been misspent over the previous six years, with Medicare

picking up the tab for payments for which private health plans actually were

liable. In 1997, federal investigators for the Department of Health and Human Services

reported that the government overpaid hospitals, doctors and other health care providers last

year by $23 billion, or 14% of all the money spent in the standard Medicare

program.

Not surprisingly, such sums triggered considerable greed. During the 1980s there were reports of

Medicare and Medicaid being billed for patients never seen, for excessive tests, and for

prescriptions never filled. In 1989, a government study by

Richard Kusserow, the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services,

found that physicians who own or invest in laboratories prescribed 45% more clinical services

for Medicare patients than did other physicians. Also that year the GAO concluded that over

$10 billion in Medicare funds had been misspent over the previous six years, with Medicare

picking up the tab for payments for which private health plans actually were

liable. In 1997, federal investigators for the Department of Health and Human Services

reported that the government overpaid hospitals, doctors and other health care providers last

year by $23 billion, or 14% of all the money spent in the standard Medicare

program.

As the 2000 Presidential election heated up the high cost of prescription drugs

and the extent to which Medicare should cover their purchase emerged as key

issues for older persons. Click

here for story of how pharmaceutical companies are battling against

government interventions in their industry.

Fact from the Files: Some 28% of Medicare expenditures are used by 5.9% ultimately

deceased older population. In other words, between one-quarter and one-third

of Medicare monies go to those in their last few months of life.

- Robert B. Helms, "The Origins of Medicare"

- Charlotte Twight, "Medicare's Origin: The Economics and Politics of Dependency"

- Health Care Finance Administration

- Official U.S. Government

Site for Medicare

- Texas Medicaid Reform

Web Server

STATE

AGENCIES

ON AGING

- State of Florida:

Department of Elder Affairs

- Bureau of Maine's

Elder & Adult Services Resource Directory

- North

Central-Flint

Hills Area Agency on Aging; page 1

- Texas Department on

Aging

- Texas Dept.

of Protective and Regulatory Services: Preventing abuse

ADVOCACY

Lobbying groups on behalf of older persons have proliferated in the past two

decades, profoundly shaping federal social policy. The Leadership Council of Aging Organizations

now lists 40 such groups, up from 29 in 1988. They are the latest stage in the history of the

senior movement, which, according to Armond Mauss in Social Problems as Social

Movements, can be typified thusly:

- Incipiency: (1920-49) old-age pension movements, Townsend Movement, Social

Security, founding of National Retired Teachers Association (1947);

- Coalescence: (1950-69) National Council On the Aging founded (1950),

American Association of Retired Persons founded, 1961 White House Conference on Aging,

Senate Special Committee on Aging (1961), NCSC founded in 1961, Medicare, Older

Americans Act (1965), establishment of Administration on Aging;

- Institutionalization: Gray Panthers founded (1970), 1971 White House

Conference on Aging, 1972 Social Security Amendments, House Select Committee on Aging

(1974), National Institution on Aging (1974);

- Fragmentation

- Demise: abolition of Congressional select committees on aging?

The Townsend Movement is a fascinating chapter in this history. In the early

thirties amidst the Great

Depression, Francis Townsend, a California physician, had an economic model for

getting America out of its plight involving the velocity of money: the government would give

$200 a month (or, according to my calculations, $2,339 in 1997

dollars) to all individuals over the age of 60, who, in turn, would be required to spend it.

Needless to say, with over one-half of the nation's old living in poverty, the popularity of this

idea was considerable. Over five million older persons joined Townsend clubs around the

country. The number of these clubs varied considerable across

the states, ranging from nearly 38 clubs per 100,000 people in Oregon to .58 club in

South Carolina. What state level indicators predictors were associated with the popularity of

this movement? Interestingly, not the percentage of the population over 65. Among the factors

we found were (with Pearsons r): 1924 membership in the International Workers of the World

(.53), high male/female sex ratio in 1940 (.69), high rates of home ownership (.62) and the

proportion of workers in the professions (.66), and sizable Scandinavian populations (e.g.,

%Swedish=.46).

-

FirstGov for Seniors--a government portal just for older Americans

- Alliance for Aging Research--non-profit advocacy

group promoting the acceleration of geriatric research

- The

National Council on the Aging

- Elder

Abuse Prevention

GERONTOCRACIES

If there were no old men, there would

be no civilized states at all.

--Cicero

Give me a staff of honour for mine age. But not a sceptre to control the world.

--Shakespeare

Gerontocracies, or rule by the old, have received mixed

reviews throughout history.

In 44 B.C., Cicero argued how "Old men...as they

become less capable of physical exertion, should redouble their intellectual

activity, and their principal occupation should be to assist the young, their

friends, and above all their country with their wisdom and sagacity."

But with industrialization and modernization, elder

veneration decayed as did the notion of elder wisdom. In the final

quarter of the 20th century, the aging of the "founding fathers" of

Russia and China (who seemed reluctant to entrust power to younger generations

who did not know life before the revolution) came to be viewed as obstacles to

change. In the United States, there were stories of President Reagan

dozing during cabinet meetings and in his meeting with the Pope. At

century's turn, there were less

than flattering stories of nonagenarian Strom Thurmond and octogenarians

Henry Hyde, Jesse Helms and Robert Byrd. One wonders what the relationship

is between the age structure of Congress and the number of long-term goals it

establishes. For a particularly harsh indictment against older rulers see

"Conditions

Affecting the Sway of Custom" in Edward A. Ross's 1919 Social

Psychology.

THE OLD AS MINERS' CANARIES--BIOLOGICALLY, POLITICALLY AND SOCIOLOGICALLY

With their diminished biological resources, changes in the mortality rate

of elderly persons are often used as gauges of environmental change. How

hot was it? Over twenty of the city's older population died of

heat-related maladies. Flu season was harsh this year. Thirty-three

elderly members of the community have succumbed to the epidemic since New Years.

This indicator status of older persons also is a measure of societal "well-being."

Neighborhood victimization of elderly residents by young punks is a diagnosis of

sociological cancer--as those who should be accorded esteem for their years of

social contribution (and because they are most likely to know their attackers by

virtue of the correlation between length of residency and the number of one's

social contacts: "Officer, I believe one of them was Lillian's

grandson") are, because of their greater vulnerability, victimized.

Another measure of social

rot, one employed by Amnesty

International: the "humiliation of elderly people."

Return

to Social Gerontology Index

Return

to Social Gerontology Index

Former British Minister of Health, Ian Macleod, wrote that "in

the capitalist democracies, the ageing of the population has raised new

difficulties. It is the `Mount Everest' of the present day social problems."

"Not only are there many more aged people than there were," wrote

Simone de Beauvoir in The Coming of Age, "but they no longer spontaneously integrate with

the community: society is compelled to decide upon their status, and the

decision can only be taken at the government level. Old age has become

the object of policy."

Former British Minister of Health, Ian Macleod, wrote that "in

the capitalist democracies, the ageing of the population has raised new

difficulties. It is the `Mount Everest' of the present day social problems."

"Not only are there many more aged people than there were," wrote

Simone de Beauvoir in The Coming of Age, "but they no longer spontaneously integrate with

the community: society is compelled to decide upon their status, and the

decision can only be taken at the government level. Old age has become

the object of policy."

And how do Americans view this program and its effect on aged poverty?

According to The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard

University Survey Project's "Why Don't Americans Trust the Government?"

survey of late 1995 (n=1,514 adults 18 and older), when asked "Compared

with 20 years ago, do you think the share of Americans over 65 who live

in poverty has increased, decreased or stayed about the same?" some 59%

believed that it had increased (and only 15% saw a decrease). And when asked about

"what effect, if any, do you think the federal government's [old age] programs have had

on the share of Americans over 65 who live in poverty", only 23 percent thought that

they have "helped make things better" while 32 percent thought they have

"made things worse" and 39 percent seeing not "much effect either

way." According to the combined 2000-2002 NORC General Social Surveys of American adults

(n=5,297), as can be seen in the graph on the right, belief that we're spending too little on Social

Security generally decreases with age, from 66% of those in their thirties to

45% of those eighty and older.

And how do Americans view this program and its effect on aged poverty?

According to The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation/Harvard

University Survey Project's "Why Don't Americans Trust the Government?"

survey of late 1995 (n=1,514 adults 18 and older), when asked "Compared

with 20 years ago, do you think the share of Americans over 65 who live

in poverty has increased, decreased or stayed about the same?" some 59%

believed that it had increased (and only 15% saw a decrease). And when asked about

"what effect, if any, do you think the federal government's [old age] programs have had

on the share of Americans over 65 who live in poverty", only 23 percent thought that

they have "helped make things better" while 32 percent thought they have

"made things worse" and 39 percent seeing not "much effect either

way." According to the combined 2000-2002 NORC General Social Surveys of American adults

(n=5,297), as can be seen in the graph on the right, belief that we're spending too little on Social

Security generally decreases with age, from 66% of those in their thirties to

45% of those eighty and older.