Whoever controls the past controls the future. Whoever controls the present controls the past.

We used to do things for posterity; now we do things for ourselves and leave the bill to posterity.

Since the 1980s, it seems that increasingly historical matters have become issues of considerable political significance. Japan received international criticism over historical reconstructions of World War II in its textbooks and, in 2000, for hosting a conference entitled "The Verification of the Rape of Nanking: The Biggest Lie of the 20th Century." In the former Soviet Union (where the past is so routinely rewritten that the old line was "In Russia it is impossible to predict the past"), Gorbachev's glasnost resurrected dangerous memories of Stalinist purge victims and forgotten Bolsheviks. In West Germany prior to reunification, the president of parliament was forced to resign after remarking, on the eve of 50th anniversary observances of Kristallnacht, "Didn't Hitler bring to reality what (Kaiser) Wilhelm II had only promised, that is to lead the Germans to glorious times? Wasn't he chosen by Providence, a Fuhrer such as is given to a people only once in a thousand years?" (Deutsche Presse Agentur, 1988). (A decade later, Hitler apologists continue to deny the Holocaust occurred. For a particularly frightening case study in historical revisionism see Dr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr.) In the United States, controversy surrounded the memories triggered by Oliver Stone's "J.F.K.", the ritual observances given to the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the 500th anniversary of Columbus' first voyage to the New World, and the way the Vietnam War was to be remembered architecturally (see Carla Armstrong and Karen Nelson's "Ritual and Monument") and the National Park Service's The National Mall). Suspicions that there are things that business and the government want us to forget has given rise to such websites as The Memory Hole.

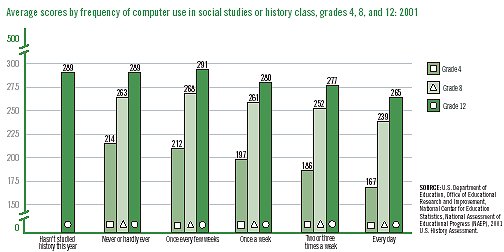

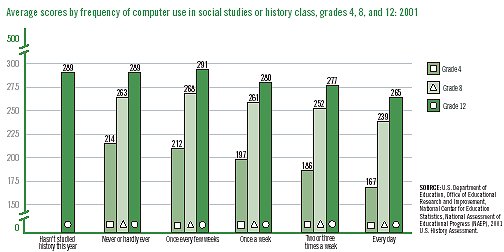

Concurrently, several studies were conducted that revealed a profound ignorance of historical matters among American students. According to "The Nation's Report Card 2001: U.S. History" (click here for the test's framework), more than one-half of high school seniors failed to demonstrate a "basic" understanding of their nation's history. As can be seen in the graph below, use of that supposed educational godsend, the computer, did not improve matters--in fact, scores generally declined with increasing use! In Diane Ravitch and Chester Finn's 1987 report "What Do Our 17-Year Olds Know?: A Report on the First National Assessment of History and Literature," it was found that the answer was little: One out of five students thought Watergate occurred before 1900 and only one-third could place the Civil War within the correct half-century. A 1993 Roper survey of American high school students (n=506) and adults (n=992) found that 38 percent of adults and 53 percent of high school students did not even know the meaning of the term Holocaust. Instances of collective amnesia appear not to be confined to this country: A 1977 study of over 2,000 West Germans aged 14 to 16 revealed that nearly half knew little about the activities of the Third Reich.

Such historical ignorance is not solely due to the progression of generations (which is, in part, why political orders observe rituals of collective remembering at 25-year intervals). For events occurring within the lifetimes of society's oldest members to become either forgotten or never learned indicates other forces at work. George Lipsitz observed:

The crisis in historical thinking is certainly real. The dislocations of the past two centuries, the propaganda apparatuses of totalitarian powers, disillusionment with the paradigms of the Enlightenment, and popular culture itself have all served to make the search for a precious and communicable past one of the most pressing problems of our time (1990:36).Add to these the dissolutive effects of post-modernism's deconstructionism and relativism and one has the contemporary cultural context for historical obliviousness. Here flourishes revisionism, whose historical narratives feature a denial of the fixity of the past, of the reality of the past apart from what the historian chooses to make of it, and thus of any objective truth about the past (Himmelfarb, 1993).

Nevertheless, despite their own deteriorations and mutations of the past, it is interesting to note how the right to remember was to permeate this century's ideological contests, with democratic regimes denouncing the "social amnesia" (Jacoby, 1975) induced by totalitarian systems. Why did the Communists hate the Jews? It was because the Jews carried their memories with them (Moyers 1986). As Paul Johnson noted, "No people has ever insisted more firmly than the Jews that history has a purpose and humanity a destiny" (1987:2).

Given such trends, the question arises: Precisely what are the implications of such nescience and/or fluidity? Common wisdom holds that historic knowledge is essential. In The American Memory, for instance, Lynne Cheney writes "By reaching into the past, we affirm our humanity. And we inevitably come to the essence of it" (1987:6). During the twentieth century, the necessity of history became understood in terms of remembering and thereby avoiding the mistakes of the past: "Never forget. Never Again," remains the pledge of Holocaust survivors who now face historical revisionists claiming that Hitler's Final Solution never occurred. Further, without such stories we become unable to appreciate the the lessons of how those of previous eras coped with life's predictable and inevitable crises. See "We Are Only What We Remember."

On the other hand, strong

cases

can be made for the need for socially structured forgetting, or structured

amnesia (the words amnesia and amnesty derive from the same

root, whose meaning is to forget [Budiansky, 1993]), in order to disregard

past generations' injustices and vendettas. Success of the 1993 Israel-PLO

accord, for instance, will require considerable forgetting. Protestants'

annual celebration of the 1690 the victory of King William of Orange over

Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne River serves little to

promote peace in Northern Ireland. And identifying World War II atrocities

as being distinctively German or Japanese serve little purpose nowadays

for American political or corporate interests. It has been argued (e.g.,

Kammen, 1991) that the consensus story binding American immigrants is not

their varied pasts (which often they were escaping) but rather their shared

future.

Such matters of collective remembering and forgetting have not gone unnoticed by sociologists, who have created numerous conceptualizations of the processes (see Middleton & Edwards, 1990) and case studies in the social construction and reconstruction of particular historical events (e.g., Schudson, 1992) and personalities (e.g., Schwartz, 1987,1990). Common to these endeavors is the appreciation human memory can only occur within collective contexts and that its contents are mutable (albeit with limitations) social constructions that serve various social interests.

Those believing that social systems have the need for some consensus story to link the historical bonds of their members and thereby provide a sense of collective identity have found affinity with the works of Durkheim (1912). From this tradition, the focus is on how social solidarity is obtained through cultural transmissions of central stories in religious observances (e.g., Zerubavel, 1982), political commemorative rituals (e.g., Kearl & Rinaldi, 1982), tradition1 (Shils, 1981), and school history texts (e.g., Ellison, 1964). Typically, these stories feature remembrance of ancestors who epitomize social ideals, legitimate contemporary causes, or who provide benchmarks against which we understand ourselves and our shared endeavors. Thus political regimes require that their histories be taught as part of their socialization of national identities just as members of the Church of the Latter Day Saints are led to focus on their family genealogies and baptismal histories in order to internalize their Mormon identities. Further, by acknowledging the sacrifices of past generations, created is a sense of one's own obligations to generations yet born.2 Sociologists of the Marxist tradition (e.g., Coser & Coser, 1963) approach false temporal consciousness as being one of the most powerful tools of oppression. Their methodology, in part, is designed to unmask the elites' uses of the past to legitimate their dominance and to create in the minds of the exploited erroneous senses of historical progress in the quality of life and social justice. From this perspective, the emergence of Black History Month and Women's History Month are viewed as reactions against dominant white male history, serving to give shape and definition to their own collective identities while uncovering discrediting memories of regime injustices.

Mannheim's (1928) approach to the past was framed in his analyses of generations and the ways in which personal biographies intersect with historical watershed events to produce historically-conscious agents of social change. Dominant generations control the reigning conceptions of history (producing "generation gaps"; with those from other historical vantage points) only to die off with their cohort-centric historical paradigm. In Germany, for instance, the 40th commemoration of Germany's capitulation at Bitburg in 1985 revealed a deep generational divide between young Germans (over half the population was born after 1945), who saw such a "gesture of reconciliation"; as unnecessary, and older cohorts who bore the guilt of supporting (or not opposing) the Third Reich. And those inspired by Mead's (1929, 1932) discussion of continuity and discontinuity investigate how novel or unpredicted events acquire their own past as new rationalities become required to account for why these phenomena have entered the present (see Maines et al., 1983). Just as people can accept false autobiographical memories that are consistent with their present self theories, the memories of social orders are not reproductions of the past but rather revisionist constructions of how they are likely to act given current ideology. This is not to imply that the reconstruction of the past is pure fantasy; it is the meaning given to its irrevocable evidence that changes. The defining events that we think are important are the incidents that will be remembered and these form a kind of coagulant around which other events are recalled, organized and given meaning (Bellah, 1986). Intriguing as these (and other) sociological traditions have been, few empirical investigations have been devised to ascertain precisely what difference it makes if individuals, indeed, have a sense of historical consciousness. This is ironic given the centrality to the discipline of C. Wright Mills' "sociological imagination," to make us

aware of the intricate connection between the patterns of their own lives and the course of world history, [as] ordinary men do not usually know what this connection means for the kinds of men they are becoming and for the kinds of history-making in which they might take part. They do not possess the quality of mind essential to grasp the interplay of man and society, of biography and history, of self and world (1959:4).To address this void, what follows are two short studies to illustrate new methodological strategies for approaching what has heretofore been either a highly philosophical or qualitative line of inquiry.

In 1993, the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) included the following open-ended question in its General Social Survey of random samples of non-institutionalized Americans aged eighteen years and older:

There have been a lot of national and world events and changes over the past 60 years --- say, from about 1930 right up until today. Would you mention one or two such events.Sixteen percent of the 1606 respondents either didn't know or couldn't think of any such event. The remainder identified at least four. The most frequently mentioned incidents included: the fall of Communism (mentioned by 32% of the respondents), World War II (by 19%), the space program (15%), civil rights (12%), and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (11%). Memories of the painful 1930s failed to surface: only 3.8% of the respondents mentioned the Great Depression and but .9% mentioned Franklin D. Roosevelt or his administration.

Less than one out of five respondents mentioned World War II or any of its associated events (e.g., Pearl Harbor or the atomic blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki). Such absence of reference to what was the defining event of the past sixty years is not because the war's participants have died out with its memories. As of 1992, there were nearly eight and one-half million American soldiers alive who served at the time (and 65,000 who served during World War I). And it is not because American society has failed to bring recollections of the war to public attention. Over the past decade American culture has been saturated with its memories, from the fortieth anniversary observances of the landing at Normandy in 1984, to the fiftieth anniversary observances of Pearl Harbor (this author counted no fewer than 14 television shows about the event on December 7, 1991), and stories surrounding the opening of the American Holocaust Museum being cover stories of the nation's major news magazines. With the collapse of the USSR and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the media was filled with hitherto secret memories of complicities and atrocities committed during the conflict. The syndicated Hearst newspapers have featured daily "50 Years Ago Today"; recollections. And between 1991 and 195, the U.S. Post Office issued annual 10-stamp sets with 50-year-old images of the America's involvement in the war.

Across the social landscape, where does this particular collective memory find its most fertile ground? Not surprisingly, there are clear correlations involving age and education. Those 65 years of age and older were three times as likely to mention the Second World War as were those 41 years of age or younger. Among the latter, those with four or more years of college education were three-and-one-half times more likely to mention the war than those with a high school degree or less.

Click here to see

Let's follow Mead's logic of how unique events of the present acquire a past. In the two figures below are diagramed the statistically significant correlations. Among older Americans, for instance, those who mentioned the Presidency of FDR were significantly more likely to mention the Great Depression than those who did not mention FDR. But notice the consequences of how the biographies of various cohorts differently intersect Mannheim's watershed events. Sixty percent of our sample of adult Americans was born after 1945; those who were ten years of age or older when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor comprise but one out of five of our respondents. Figures 3a and 3b illustrate the consequences. For Americans 18 to 35 years of age (Figure 3a) there seem to be three defining events producing Bellah's memory coagulants: civil rights (connecting memories of the feminist movement and the welfare state), the Nixon administration (prompting memories of Kennedy, Reagan and the Persian Gulf War), and World War II (which links memories of the Depression and the Vietnam War). The general absence of connections between historical events made by young adult Americans, especially when compared to those made by individuals sixty and older), brings to mind the contentions of post- modernists. These individuals, such as Lawrence Grossberg, argue that "change increasingly appears to be all that there is," that "there is no sense of progress which can provide meaning or depth and a sense of inheritance," and "both the future and the past appear increasingly irrelevant; history has collapsed into the present" (cited in Lipsitz 1990:22). As forgetting is often due to piecemeal impressions (Halbwachs 1950), many memories of the middle third of the century appear destined for oblivion.

And what difference does

even acknowledging

the second world war make? Interestingly, when controlling for age and

education, those mentioning this conflict are significantly more likely

than non-mentioners to endorse the civil rights of atheists, racists, communists

and those advocating doing away with elections and letting the military

run the country. Those not mentioning World War II were 74 percent more

likely to believe that the United States would be engaged in another world

war within ten years, a correlation that held within all age groups with

the exception of those in their fifties.

In C.S. "The Screwtape Letters," the devil, Screwtape, advises his nephew and disciple to corrupt men by cultivating in them disdain for the past. "[I]t is most important thus to cut every generation off from all others," Screwtape says, "for where learning makes a free commerce between the ages there is always the danger that the characteristic errors of one may be corrected by the characteristic truths of another" (1943:140). What better way for the devil to dissolve the commerce of intergenerational lessons than to promote disrespect for the old?

This historical perspective is the special knowledge possessed by the old, as noted by Daniel Callahan:

The unique capacity of the elderly to see the way the past, present, and future interact provides the foundation for the contribution they can make to the young and to future generations. ...[The Old] should know that they have their own debt to the past and that from that debt springs their own obligation to the future. ...If we value our own life at all, then we should value and feel some obligation toward those who made that life possible, our own families and the past societies which supported them. We owe to those coming after us at least what we were given by those who came before us, the possibility of life and survival (1987:47).Such impartings of historical perspective from older to younger generations typically occurs within family systems, wherein grandparents "serve as a link between the child and the preceding generation, bringing continuity to the family and knowledge of previous eras" (Linder, 1978:14). Maurice Halbwachs goes so far as to speculate that this temporal outlook is at least partially the essence of the grandparent-grandchild bond:

The child is provided access to an even more distant past by his grandparents. Perhaps grandparents and grandchildren become close because both are, for different reasons, uninterested in the contemporary events that engross the parents. ... [The child] is aware that, for his grandparents, he somewhat replaces his parents, who should have remained children and not become totally involved in contemporary life and society. Their stories, oblivious of the times and linking the past and future together across the present, could not help but intrigue him, just as stories about himself might. What becomes fixed in his memory are not just facts, but attitudes and ways of thinking from the past. ...the personage of an aged relative seems to grow in our memory as we are told of a past time and society (pp. 63-4)._ With these thoughts in mind, let us explore the connection between historical knowledge, ideological orientations toward the present and future, and respect for the insights of the old.

Methods

In 1988 this researcher administered two hundred questionnaires to south Texas undergraduate students at both an undergraduate liberal arts institution and a city university.

To gauge their degree of historical knowledge, results of their placing events on a time line (see Appendix I) were analyzed. First, two scores were computed: a rho score to measure the ordering of events and a scale that tallied the total number of decades respondents were off in their event placements. Second, given the high correlation between these raw scores (r=- .86), these two scores were recoded into quintiles, which, in turn, were multiplied and recoded into quintiles.

The corresponding mindsets assumed to be associated historical ignorance were derived from arguments from numerous popular and academic sources, ranging from various conspiracy theories of history to measures of alienation to beliefs that America's Golden Age has either passed or is yet to come.

Findings

The degree of historical ignorance was considerable. Even at the elitist private university we found: the Russian Revolution occurring in 1970, the first atomic device detonated in 1915, manumission of American slaves occurring as early as 1830 and as late as 1910, the Peoples Republic of China coming into existence in 1790 and 1880 and Israel in 1810, the Napoleonic war preceding the French Revolution and occurring as recently as the 1880s, Darwin writing in the 18th century, and American women receiving the right to vote as early as 1810. The mean rho score of the order of events was .56 with a standard deviation of .316. The mean of the total number of decades individuals were off in their placements of events (with the maximum being capped at 100) was 46.9 with a standard deviation of 25.2 decades.

Among the measures of mindsets supposedly associated with ahistoricity it found that:

- one-half of the respondents think that ultimate political power is held by special interest groups such as the military industrial complex;

- only one-third believe that the American political system attracts talented individuals;

- fifty-eight percent thinking that America's Golden Age has passed;

- nearly one-quarter believing that the U.S. suffers when developing nations prosper;

- and that four out of ten acknowledging that divisive elements must be located and eliminated or else our nation is in danger of disintegrating.

The degree of historical knowledge possessed produces significant correlations with five of our mindset measures. The greater the degree of historical ignorance the more likely one is to believe that:

- America suffers when the Third World Prospers;

- divisive elements need to be located and eliminated or our society risks disintegration;

- those with power attempt to take advantage of less powerful others;

- contrary to what experts say, there are simple solutions to many of the nation's problems.

Historical ignorance was significantly related to the beliefs that America's Golden Years have yet to come and that evil political figures have been working to destroy the morality and freedoms of this country suggest how the absence of historical perspective is bound-up with the authoritarian personality. This brings to mind the social psychological chemistry of the Weimar Republic that spawned National Socialism, how rising expectations were to be dashed and the dynamics of witchhunts and scapegoating were then to be unleashed.

Historical ignorance also significantly correlated with the idea that the elderly have little of relevance to teach the young. In fact, of all of the measures considered, it was this variable that produced the greatest number of significant correlations. For instance, when compared with those who strongly disagreed that the old have little of relevance to teach the young:

- those who disagreed somewhat were 44 percent more likely and those who agreed were over twice as likely to believe that there once was an era in American politics when there was relatively no disagreement on major issues;

- those who disagreed somewhat were 2.4 times more likely and those who agreed were 2.9 times more likely to agree that the U.S. is weakened with the Third World prospers;

- those who disagreed somewhat were 39 percent more likely and those who agreed were 84 percent more likely to believe that America's Golden Years have yet to come;

- those who agreed were more than one-third more likely to believe that divisive elements need to be located and eliminated or our society risks disintegration;

- those who disagreed somewhat were 26 percent more likely and those who agreed were 86 percent more likely to believe that the American political system attracts as talented individuals as ever for public office.

Discussion and Conclusion

Unlike many of their cultures of origin, Americans do not normally have as strong ties to their heritage; they perceive their biographies to be generally independent of history and the deeds of their ancestors. Further, there are few institutional imperatives requiring a historical sense: native-born Americans, after all, can still vote even if they think that George Washington was a horse; and unlike the Nuer, who can generally recall nine to eleven generations of their ancestors (Evans- Pritchard, 1940), Americans don't have to know relatives connected at the fifth generation to lay claim to their wedding gifts. In addition, the significance of the past has dissolved owing to the destructive forces of individualism (which leads to generational solipsism), capitalism (which yields a cultural orientation toward future profits), and democracy (which, as John Adams observed, makes us forget our ancestors). For these reasons, the line "do that and you're history!" no longer means that such actions will be remembered for posterity but rather that one's existence will be forgotten.

And yet the fact that the late-1970s "Roots" series remains the record-holder as the proportionately most-watched television show in history (despite 28 increasingly-hyped Superbowls) can be taken as evidence that, if properly triggered, this sense of intergenerational connectedness addresses some primal need dating back to our tribal heritage. Religions know this well, which is why representations of continuity are deeply woven within their symbolism. Within religious temporal frames of reference, individuals come to understand that their biographies are not separate volumes on that bookshelf of existence, but rather are chapters of far grander stories that integrate the fates and responsibilities of generations long dead with those now alive and those yet to be born. It is for this reason that strongly religious people were the first great historians (Innis, 1951:67- 68).

Despite this presumed importance of historical knowledge, there is a peculiar absence of empirical demonstration of this common wisdom. In the two studies presented is evidence suggesting that such insight perhaps does make a difference. Why should those remembering World War II be more supportive of the civil liberties of unpopular groups? No significant connections were made between memories of World War II and the social movements of African Americans and women (though those over age 60 did make connections between Roosevelt and the feminist movement and the welfare state). Perhaps the memory is associated with some of the meanings of that war, namely the rights of minority groups against state censorship or prejudice.

Having greater control over the questions of the second study allowed us to see how historical ignorance is interwoven with authoritarianism and utopian thinking. Given America's absorption into the world system, can we afford too many individuals believing that America suffers when developing nat ions prosper? Given the moral relativism and multiculturalist ethos of our times, can we cope with too many individuals believing that their society will disintegrate unless its divisive elements are located and eliminated--the same folks who surmise that there really are simple solutions to many of our problems? Such are the features the worldview of those failing to understand the order and timing of historical events.

References

Bellah, R. (1986) Public Lecture on the Sesquicentennial of the Fall of the Alamo. Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas (Feb. 28).

Budiansky, S. (1993) "The Place Where the Past Is Never Dead." U.S. News & World Report (March 29):6-7.

Callahan, D. (1987) Setting Limits: Medical Goals in An Aging Society. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Cheney, L. (1987) American Memory: A Report on the Humanities in the Nation's Public Schools. Washington, D.C.: National Endowment for the Humanities.

Coontz, S. (1992) The Way We Never Were: American Families & the Nostalgia Trap. Basic Books.

Coser, L., and Coser, R. (1963) "Time Perspective and Social Structure," in A. Gouldner and H. Gouldner (eds.), Modern Sociology, pp. 638-50. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Davis, F. (1979) Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York: The Free Press.

Deutsche Presse Agentur (1988) "Official calls Hitler era `glorious.'" Reported in San Antonio Express-News (Nov. 11):3A.

Ellison, R. (1964) Guardians of Tradition: American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Evans-Pritchard, E. (1940) The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Halbwachs, M. (1980 [1950]) The Collective Memory (F. Ditter, Jr. and V. Ditter, trans.). New York: Harper Colophon Books.

Himmelfarb, G. (1994) On Looking Into the Abyss: Untimely Thoughts on Culture and Society. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Innis, H. (1951) The Bias of Communication. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Jacoby, R. (1975) Social Amnesia. Boston: Beacon Press.

Johnson, P. (1987) A History of the Jews. New York: Harper & Row.

Kammen, M. (1991) Mystic Chords of Memory. New York: Knopf.

Kearl, M., and Rinaldi, A. (1983) "The Political Uses of the Dead as Symbols in Contemporary Civil Religions." Social Forces 61(3):693-708.

Lewis, C. 1943. The Screwtape Letters. New York: Macmillan.

Linder, B. (1978) How to Trace Your Family History. New York: Everest House.

Lipsitz, G. (1990) Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Maines, D., Sugrue, N., and Katovich, M. (1983) "The Sociological Import of G.H. Mead's Theory of the Past." American Sociological Review 48:161-173.

Mannheim, Karl. (1952 [1928]) "The Problem of Generations," in K. Mannheim, Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, pp. 276-322. London: Routledge and Kegal Paul.

Marx, K., and Engels, F. (1930) The Communist Manifesto. New York: International Publishers.

Mead, G. (1929) "The Nature of the Past," in J. Coss (ed.), Essays in Honor of John Dewey, pp.235-42. New York: Henry Holt.

(1932) The Philosophy of the Present. LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing.

Middleton, D., and Edwards, D. (eds.) (1990) Collective Remembering. London and Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mills, C. (1959) The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moore, W. (1963)Man, Time, and Society. New York: Wiley.

Moyers, B. (1986) Public presentation at Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas (Sept.30).

Ravitch, D., and C. Finn, Jr. (1987) What Do Our 17-Year- Olds Know? A Report on the First National Assessment of History and Literature. New York: Harper & Row.

Schwartz, B. (1990) "The Reconstruction of Abraham Lincoln, 1865- 1920," in D. Middleton and D. Edwards (eds.), Collective Remembering, pp. 81-107. London: Sage.

(1987) George Washington: The Making of an American Symbol. New York: The Free Press.

Schudson, M. (1992) Watergate in American Memory: How We Remember, Forget, and Reconstruct the Past. New York: Basic.

Shils, E. (1981) Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zerubavel, E. (1982) "Easter and Passover: On Calendars and Group Identity." American Sociological Review 47:284-89.

![]()