"A reality can hardly seem self-evident

if a person is simultaneously aware of a counter reality."

--Joan Emerson

Having considered matters of self, motivation, and affect, as well as how they interact with with setting, let's explore their bearing on behavior. For an example of what kind of theoretical model these processes entail, see Broadbent's "Personality, motivation, and performance."

![]() The range of our social interactions produces a wide

spectrum of connections with others, from the anonymous relations with

total strangers to the communal ties with certain others whose identities

become thoroughly intertwined with our own. Connecting with others is a

central biographical theme for all of us. According to James Q. Wilson

in The Moral Sense, "Just as Labradors are born to fetch, we

are born to bond." To appreciate the potency of these connections,

all that one needs to see is what happens when these ties are severed:

a spouse dies, one is fired or retired from

work, a close friend moves to another state, or one's

parents divorce.

The range of our social interactions produces a wide

spectrum of connections with others, from the anonymous relations with

total strangers to the communal ties with certain others whose identities

become thoroughly intertwined with our own. Connecting with others is a

central biographical theme for all of us. According to James Q. Wilson

in The Moral Sense, "Just as Labradors are born to fetch, we

are born to bond." To appreciate the potency of these connections,

all that one needs to see is what happens when these ties are severed:

a spouse dies, one is fired or retired from

work, a close friend moves to another state, or one's

parents divorce.

In Intimate Environment, Arlie Skolnick observes:

Paradoxically, individualism seems to foster not only a preoccupation with the self, but also an emphasis on close personal relationships. As Murray Davis (1973) observes, a preoccupation with friendship and love emerged during every period of urbanization in Western culture: in ancient Greece, in the Roman empire, during the Renaissance, and, most recently and extensively, since the eighteenth century. Without the traditional bonds of kinship and community, the urban individual must construct a more consciously chosen social life to replace the world that was lost (1992:239).

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE INITIAL BOND

The social sciences, particularly psychology's

attachment theorists, have long postulated on the significance of the

first bond. The child's attachment with its mother has long been suspected

of being the bond upon which all eventual social bonds are based. Kennell

and Klaus (1972) showed that as few as 16 hours of close contact between

mother and infant immediately after birth produced better results on child

development scales as late as five years after. Investigations into the

drives of society's most deviant members invariably include stories of

dysfunctional families and abuse at the hands of those they, as children,

should have been able to count on most: the parents.

The social sciences, particularly psychology's

attachment theorists, have long postulated on the significance of the

first bond. The child's attachment with its mother has long been suspected

of being the bond upon which all eventual social bonds are based. Kennell

and Klaus (1972) showed that as few as 16 hours of close contact between

mother and infant immediately after birth produced better results on child

development scales as late as five years after. Investigations into the

drives of society's most deviant members invariably include stories of

dysfunctional families and abuse at the hands of those they, as children,

should have been able to count on most: the parents.

FRIENDSHIPS

WHEN BONDS DISSOLVE

![]()

To be considered here is how individuals--these self-conscious creatures

of symbols who, among other things, seek meaningfulness, connections with

others, and esteem--interact, and how out of their interactions emerge

both personal and social order. Like the act of

driving, behaving in everyday life follows specified pathways (society

is, after all, but networks of patterned social activity) replete with

rules that are both written and unwritten. These rules, in part, require

a definition of self vis-à-vis other types of selves: are one's self performances

to directed toward a social superior or subordinate, a store clerk or a

friend, an intimate or a total stranger?

These rules assist interactants to anticipate others' behaviors and to

know how to respond accordingly. Hence we get upset with drivers who suddenly

and without warning switch into one's lane: they are in their own little

world, oblivious to their social surroundings, and fail to signal their

intents. Commonalities among "good drivers" (as measured by number

of accidents) involve both their giving appropriate signals to others and

their ability to correctly read (or assume) the intentions/motivations

of other actors.

To be considered here is how individuals--these self-conscious creatures

of symbols who, among other things, seek meaningfulness, connections with

others, and esteem--interact, and how out of their interactions emerge

both personal and social order. Like the act of

driving, behaving in everyday life follows specified pathways (society

is, after all, but networks of patterned social activity) replete with

rules that are both written and unwritten. These rules, in part, require

a definition of self vis-à-vis other types of selves: are one's self performances

to directed toward a social superior or subordinate, a store clerk or a

friend, an intimate or a total stranger?

These rules assist interactants to anticipate others' behaviors and to

know how to respond accordingly. Hence we get upset with drivers who suddenly

and without warning switch into one's lane: they are in their own little

world, oblivious to their social surroundings, and fail to signal their

intents. Commonalities among "good drivers" (as measured by number

of accidents) involve both their giving appropriate signals to others and

their ability to correctly read (or assume) the intentions/motivations

of other actors.

Social situations vary, of course. Our driver may find himself on

the roads of a foreign country with traffic going in directions opposite

to that in the United State, with unintelligible signs and customs. Such

are the experiences of immigrants and foreign travelers in everyday life.

Or one may be in competition on the Indianapolis 500 race track, where

the goal is not going from point A to B but rather to reach a waving checkered

flag first. In addition to requiring definitions of self, the rules which

channel social behavior require interactants to have a shared definition

of the situation.

Social situations vary, of course. Our driver may find himself on

the roads of a foreign country with traffic going in directions opposite

to that in the United State, with unintelligible signs and customs. Such

are the experiences of immigrants and foreign travelers in everyday life.

Or one may be in competition on the Indianapolis 500 race track, where

the goal is not going from point A to B but rather to reach a waving checkered

flag first. In addition to requiring definitions of self, the rules which

channel social behavior require interactants to have a shared definition

of the situation.

As complicated as all of this sounds, most of the time we basically

run on automatic, like mindlessless

traversing the same roads at the same time day in and day out. In some

social settings, however, individuals become conscious of these frameworks

that define their interactions with other people: there might be defining

props, such as stained glass windows conveying religious messages, or environmental

constraints, such as the zig-zagging roped-in waiting lines at Disneyland.

In other settings, individuals can become increasingly self-conscious of

themselves, as when

one has an audience evaluating one's performance such as when our driver

is a 16-year-old taking a driving test with a state examiner sitting in

the passenger seat.

DEVIANCE & SOCIAL CONTROL

Crime in the

According to at least one 1990s survey, more than 9 in 10 Americans say that they lie regularly. While some social critics interpret this as a symptom of living in a culture of lives, all evidence points to the universality of the activity.

Some sociobiologists argue that the human brain evolved with the complexity that it did, in part, because this primate had to deceive and to detect deception in order to survive and pass on its genetic code in its elaborate social environment. In other words, the absence of trust requires individuals to become skilled lie detectors. However, research by Paul Ekman indicates that we are quite inept.

Marc A. Smith and others at Microsoft are engaged in some fascinating analyses of our electronic

interactions and the new social structures being formed. At the 2001 annual meeting of the ASA, he presented

"Data Mining Social Cyberspaces" using information derived from his newsgroup

tracker.

Marc A. Smith and others at Microsoft are engaged in some fascinating analyses of our electronic

interactions and the new social structures being formed. At the 2001 annual meeting of the ASA, he presented

"Data Mining Social Cyberspaces" using information derived from his newsgroup

tracker.

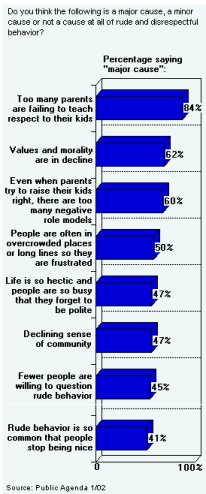

Each semester Trinity's Social Psychology class breaks into several groups to research a particular phenomenon and to produce collective projects. During the Fall of 2002 we focused on the supposed rise of the American culture of rudeness.

Within weeks of the national unity and shared civilities experienced immediately after 9-11, there appeared media claims of growing rudeness in American society. In April 2002, a poll by Public Agenda was released reporting how nearly 8 in 10 Americans believe that the lack of respect and courtesy is a serious problem, with 6 in 10 perceiving the problem is getting worse and 4 in 10 confessing that they themselves were sometimes part of the problem.

Examples:

So what accounts for such phenomena: different type of personalities or different types of

social settings? For instance, do modern

self-systems no longer come with the checks on personal

incivility that earlier models had? Do people find themselves thoughtlessly acting rudely even if they

did not intend to? Might the rudeness impulse be historically constant and what

we’re witnessing nowadays is the failure of traditional social checks (i.e., public embarrassments inflicted on those who act rude) on such behavior?

Or perhaps might the degree of rudeness be historically constant and

people nowadays are simply more sensitive to snubs and disses? Or, because of the

speed of technological change, the human primate (who shares 98+% of its genes

with chimps) now finds himself in novel contexts for which he has not been

genetically hardwired to cope with. How

well does a chimp cope with rush hour in LA? Let's line up the (usual) suspects:

Unlike the good

old days of the cold war when we feared the Reds, now we fear each other. We lock ourselves into gated communities in

homes filled with alarms and motion detectors (Joan Ryan, “Too panicked to live,” But have things

really changed? How do we know? In fact, there may not have been any real

Golden Age of etiquette, according to Mark Caldwell’s A Short History of

Rudeness and C. Dallett Hemphill’s Bowing to Necessities: A History of

Manners in The group studies:

"If men define situations as real, they

are real in their consequences." Interpersonally, defining

the situation is the matter of whose perspective frames the way in which social

phenomena are collectively perceived (or ignored) and understood (both

cognitively and emotionally). In terms of gestalt,

involved in framing is determining which social elements (which may be material

objects, individuals, values, or beliefs) are to be conceptualized as being

related and how: e.g., kin vs. non-kin, ally vs. foe, good vs. evil, just vs.

unjust, sacred vs. profane, and mine/ours vs. others. Framing

involves both differentiating figure

from ground (which, according to Maurice Merleau-Ponty, is how meaning is assigned) and thesis from antithesis. Experimentally, for instance, say a researcher gives two

groups 15 objects and tells each group to create 3 or 4 categories by which

these objects can be sorted. Each group, however, is given a different

sorting principle (i.e., sort in terms of their composition [e.g., metal, wood,

..], their use, meaning, etc. Then have the audience try to guess and

employ the classification's organizing principle.

Given the significance of controlling the dominant

gestalt- ordering frameworks of social life, it is not surprising that

groups routinely compete to dominate these definitions of situations.

Political regimes, for instance, may attempt to impose a frame through disinformation

campaigns, propaganda, music (which can create desired collective emotions), and

the substance of school curriculums. In

fact, a label has emerged for those whose work is to reframe possibly damaging

political occurrences: spin doctors. George Zito notes in The Death of Meaning (Praeger, 1993):

Ideologies are attempts to impose definitions favorable

to the group or camp espousing them. Once such definitions are imposed

they need not convince anyone of their "truth" or "reliability."

They have consequences by virtue of their mere expression and latent appeal

to the frustrated individual. Indeed, only the "true believers"

believe these definitions are "true" and are taken for granted.

(pp. 117- 8) For instance, consider the following illustrations:

These issues of framing and defining situations brings

up the matters of social power and influence. Shared "realities"

exist because some groups have more power than others, meaning that they

are able to impose their belief systems and behavioral scripts over the

less influential. Related resources: Mental

Health Net's "How dependent are we? What makes us so dependent?"--an

overview of compliance and obedience with focus on individual-level predispositions

"Nobodies don't get booed." Many individuals are a tad uneasy in this era of video and movie

cameras. Perhaps your father is continually pointing the camera at you

and telling you to do something for the family anthology. You do something

stupid, and for years afterward you cringe in embarrassment every time

the tape is shown. In fact, the spectators of that captured moment may

eventually include people you did not know at the time, such as new friends,

one's future spouse, and perhaps even your children. Why does one often feel awkwardness when one knows that one is being

videotaped? Aren't other people always watching us and remembering what

they see and hear? This is so, but the "video clips" that others

have of you might be recorded over by subsequent events. In any case, the

tapes are edited by perception and memory and are easily distorted. Unlike the traditional photograph, the recorded self is accountable

not only visually but auditorily, and over considerable periods as opposed

to a fraction of a second. (This has had an interesting effect on the political

process. Candidates, realizing that every utterance may be captured and

available for replay if their actions veer from what they promise, have

become more self-conscious, more guarded, and perhaps less willing to take

chances.) We take on faith that what we see on television is fact, not

some memory and interpretation by an eyewitness. So when we see and hear

ourselves as others do--without the thoughts and feelings that, for us,

were also part of the recorded situation--an uncomfortable detachment occurs.

We see, for instance, how little of ourselves really "gets through,"

how little of the self-image that we thought we were transmitting was really

being conveyed. By watching ourselves on television, we see the normally

invisible qualities of ourselves: We did not appreciate how many "uhs"

and "ums" had infected our speech; we did not know that we made

so many goofy gestures and facial expressions when we talked; we did not

know that this was the self that we were presenting to others.

More significantly, impression management is a function of social

setting. Erving

Goffman portrays everyday interactions as strategic encounters in which

one is attempting to "sell" a particular self-image--and,

accordingly, a particular definition of the situation. He refers to these

activities as "face-work." Beginning by taking the perspective

of one of the interactants, and he interprets the impact of that person's

performances on the others and on the situation itself. He considers being

in wrong

face, out of face, and losing face through lack of tact,

as well as savoir-faire (diplomacy or social skill), the ways

a person can attempt to save face in order to maintain self-respect,

and various ways in which the person may harm the "face" of others

through faux pas such as gaffes or insults. These conditions occur

because of the existence of self presentational rules. These rules, in

turn, are determined by how situations are defined. For instance, there

is greater latitude in social situations than in task-oriented situations.

Situations also dictate available roles and how much self-importance people

can sustain. In our post-industrial context, increasingly the work we do involves

not only the manipulation of information but strategic interactions with

others. With the expansion of the service sector has emerged a self-marketing

industry. By the mid-1980s, the 1970's Winning by Intimidation had been

replaced by winning through common courtesy, evidenced by the rise of etiquette

consultants for corporate executives. Not surprisingly, increased self-consciousness

has resulted, leading to greater caution and lesser spontaneity in everyday

interactions. Also emerging on the social landscape are increasing numbers

of a new social creature: social chameleons who strive to make the best

impression they can in every situation (see Mark Snyder's Public Appearances,

Private Reality and The Many Me's of the Self-Monitor). Clothes make the man. Naked people have

little

or no influence in society. As developed in our discussions of the body self, clothes make the person.

Here, in the context of presentations of self, we consider how clothing

communicates individuals' positions within status hierarchies and their claims

to social power and the deference of others. Clothing also can carry

political messages, such as when Gandhi

pushed the production of unrefined

cloth, or khadi,

to symbolize the idea of Indian swadeshi, or self-reliance

The notion of reputation

sheds further light on both how situations are framed and the social bases of identity. A

reputation involves others' shared image of an individual and its associated esteem.

Reputations, whether good or bad or deserved or not, filter how others interpret one's self

presentations. Acts of kindness of a reputed SOB are, for instance, interpreted differently than

are the same acts performed by a religious missionary. Enter matters of

sincerity and deception, whether others "buy" one's performance. And from the

perspective of one who knows his or her reputation, we can see how reputations can determine

the range of selves that our actor can present to others, such as the presentations one must give

to preserve one's "good name" or to restore a positive

reputation that previously had been "lost."

It is certainly in the interest of universities to increase the bonds

between their students. Consider the ways in which your college or university

attempts to amplify the interpersonal attractions of its undergraduate

population. Here at Trinity University we find: Thus far in these pages we have considered how social behavior develops

through the processes of cognition and motivation; how perhaps the deepest

human motivations are the needs for attention and respect; how symbolic

systems shape cognition, anticipation, and history; and how individuals

manage their presentations of self to make their claims on the distribution

of attention and power between individuals. However, these personal processes are interwoven with processes that

are more collective in nature. Think, for instance, about the proportion

of your activities that are determined by groups. Your presence in this

very course was made possible because of a group we call an organization.

It is this group determines your role and that of your instructor, as well

as the vast proportion of our activities during the academic year. In addition,

the time you spend writing a letter home is a product of your membership

in another group we call a family. Observe that even when you are not physically

within a group how you can still carry your membership within your head--often

our behavior is oriented toward our reference groups. In sum, it can be

argued that most of our activities are group-based. We are linked to groups

through the roles that we play and the essence of these roles is not so

much determined by personality attributes of the role occupant but rather

by the nature of the group. Further, definitions of situations are typically

made by groups, as are personal motivations (whereas much of the adult

population is pecuniarily motivated, students work for a letter of the

alphabet!).

DEFINING THE SITUATION

--W. I. Thomas ![]() Enter matters of social power, such as

the gift of imposing: how authority is obtained over how a situation is

to be defined. Unless agreed upon, performances cannot unfold. (I recall

several weekend days when my young sons would throw tantrums unless a friend

could come over and then, when the much awaited-for friend arrived, spending

entire afternoons debating what they should do.) In sum, how things are

"framed" (defined by Erving Goffman in Frame Analysis

as "schemata of interpretation" that enables individuals "to

locate, perceive, identify, and label occurrences within their life space

and the world at large" [1974:21] ) determines how they are to be

interpreted. Once a situation is defined and perceived as real,

as W. I. Thomas observed, it becomes real in its consequences: it becomes

a "self-fulfilling prophecy."

Enter matters of social power, such as

the gift of imposing: how authority is obtained over how a situation is

to be defined. Unless agreed upon, performances cannot unfold. (I recall

several weekend days when my young sons would throw tantrums unless a friend

could come over and then, when the much awaited-for friend arrived, spending

entire afternoons debating what they should do.) In sum, how things are

"framed" (defined by Erving Goffman in Frame Analysis

as "schemata of interpretation" that enables individuals "to

locate, perceive, identify, and label occurrences within their life space

and the world at large" [1974:21] ) determines how they are to be

interpreted. Once a situation is defined and perceived as real,

as W. I. Thomas observed, it becomes real in its consequences: it becomes

a "self-fulfilling prophecy."

"REALITY" AS A SOCIALLY-CONSTRUCTED

PHENOMENON

MATTERS OF SOCIAL

INFLUENCE

CLASSIC EXPERIMENTS IN OBEDIENCE

AND THE POWER

OF SITUATIONS

PRESENTATIONS OF

SELF

--Reggie's Observation  People continually attempt to manage their self-image. (It's worth

noting how the word person derives from the Latin persona, meaning

mask.) Teenage girls

and boys, for instance, spend considerable time fixing their image so as

to be appealing to others-- perhaps assuming others will give them the

attention that they give themselves. Through designer jeans, serious expressions,

gestures, joking behavior, and other devices, we present images of ourselves

that we wish others to accept and to respect. With cosmetics, veils, sunglasses,

and beards, we mask all or part of ourselves either to disguise ourselves

or to compensate for feelings of powerlessness.

People continually attempt to manage their self-image. (It's worth

noting how the word person derives from the Latin persona, meaning

mask.) Teenage girls

and boys, for instance, spend considerable time fixing their image so as

to be appealing to others-- perhaps assuming others will give them the

attention that they give themselves. Through designer jeans, serious expressions,

gestures, joking behavior, and other devices, we present images of ourselves

that we wish others to accept and to respect. With cosmetics, veils, sunglasses,

and beards, we mask all or part of ourselves either to disguise ourselves

or to compensate for feelings of powerlessness. YOU ARE WHAT YOU WEAR

--Mark Twain

REPUTATIONS

![]()

CREATING COLLECTIVE

BONDS:

THE CASE OF SCHOOL SOLIDARITIES

Avoiding Columbines

![]()

GROUP DYNAMICS

Hatred toward members of perceived out-groups is a powerful source

of in-group solidarities. Times of economic and political uncertainty spawn

various hate groups, attracting individuals, often young adults, who feel

left out of the mainstream and who feel to be in possession of some absolute

truth. While other countries may have their Fundamentalist religious zealots,

in the United States such extremism is more often bred by economics and

politics. Here potential targets for dehumanization--African-Americans,

Asian-Americans, Jews, Catholics--are more numerous because of the heterogeneity

of the American Melting Pot. Click here to see state

lynching rates 1882- 1927.

Hatred toward members of perceived out-groups is a powerful source

of in-group solidarities. Times of economic and political uncertainty spawn

various hate groups, attracting individuals, often young adults, who feel

left out of the mainstream and who feel to be in possession of some absolute

truth. While other countries may have their Fundamentalist religious zealots,

in the United States such extremism is more often bred by economics and

politics. Here potential targets for dehumanization--African-Americans,

Asian-Americans, Jews, Catholics--are more numerous because of the heterogeneity

of the American Melting Pot. Click here to see state

lynching rates 1882- 1927.

![]()