SOCIAL RHYTHMS,

CYCLES, and

CLOCKS

Although the concept of a group often brings to mind spatial connotations,

such as the different neighborhoods of a city or the "turfs"

of street gangs, groups can also be understood as temporal systems. Members

of work groups, for instance, cross the temporal boundary between family

and work when they "punch in" at the company time clock. They

are reminded of the pressures of group existence through such exhortations

as "don't waste time" and "time is money." Mothers

attempting to get all family members to the dinner table for a shared meal

are attempting to reaffirm family solidarity through establishing the centrality

of family time boundaries. It is the group that creates "time to get

serious," "born-again experiences," the pressures of deadlines,

and the daily, weekly, monthly, and seasonal flows of activities. As Emile

Durkheim observed in The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life,

it "is the rhythm of social life which is at the basis of the category

of time."

|

FACTOID

The Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. has 365 steps, representing

every day of the year. |

Pitirim Sorokin (Sociocultural Causality, Space, Time, 1943)

noted how human life is an persistent competition for time by various social

activities and their often conflicting motives and objectives. With Robert

Merton, he illustrated the significance of associating a group activity

or event with a temporal setting, thereby reaffirming the centrality of

the group to the individuals who observe its temporal demands as well as

coordinating activities that promote group solidarity and/or productivity.

"They arise from the round of group life, are largely determined by

the routine of religious activity and the occupational order of the day,

are essentially a product of social interaction" ("Social Time:

A Methodological and Functional Analysis," The American Journal

of Sociology, 1937:621).

And what conceptual scheme is to be used for analyzing these temporal

patternings of social life? Consider the following elements that Robert

Lauer (Temporal Man) and others have focused on:

- temporal patterning, whose elements include periodicity, tempo,

timing, duration, and sequence. For instance, consider the extent to which

group times specify daily, weekly, monthly, and annual cycles of activities.

- temporal orientation: the group's rank-ordering of the primacy of

the past, present, and future;

- and temporal perspective: the positive or negative value placed

on the past, present, or future by the group.

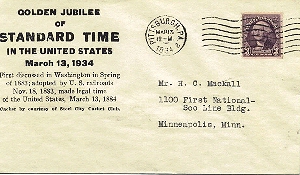

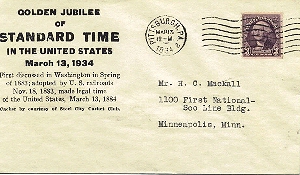

STANDARD TIMES

It's hard to believe that only about a century ago most towns in

this country had their own time. The hands of the clock in the town square

would be synchronized with cosmos, "high noon" being established

when the sun being at its highest point for the day. But owing to technological

innovations (particularly the railroads, whose schedules of arrival and

departure times required greater temporal uniformity) and enhanced interdependencies

between social members, "standard time" emerged. This replacement

of local time- reckoning with supralocal standards of time marked a fundamental

change in our relationship to time: human activity was to be increasingly

oriented to social as opposed to natural times. Take a look at WebExhibits

Calendars Through the Ages

for "the fascinating history of the human endeavor to organize our

lives in accordance with the sun and stars," and Simon K. Chung's

Chronology

for an illustrated history of the clock in the West.

It's hard to believe that only about a century ago most towns in

this country had their own time. The hands of the clock in the town square

would be synchronized with cosmos, "high noon" being established

when the sun being at its highest point for the day. But owing to technological

innovations (particularly the railroads, whose schedules of arrival and

departure times required greater temporal uniformity) and enhanced interdependencies

between social members, "standard time" emerged. This replacement

of local time- reckoning with supralocal standards of time marked a fundamental

change in our relationship to time: human activity was to be increasingly

oriented to social as opposed to natural times. Take a look at WebExhibits

Calendars Through the Ages

for "the fascinating history of the human endeavor to organize our

lives in accordance with the sun and stars," and Simon K. Chung's

Chronology

for an illustrated history of the clock in the West.

THE DAILY CYCLE

The day that starts bad, ends bad.

--Old Mexican saying

Even though human activities have become increasingly divorced from

the natural rhythm of day and night, society still often specifies that

certain things should be done during certain times of the day. Consider,

for instance, our temporal socializations during the school day. Students

are taught that certain subject matters are to be studied during specific

times of the day. "Johnny, put away those crayons! Art time is over

and math time has begun." Querie: Are there certain times of the day

when we are best able to do math, social studies, music or art? Consider

looking at the mean grades given to students who take the same course with

the same instructor but at different times of the day.

Individuals vary considerably in terms of their preferred times of

the day. During the Fall and Spring terms of the 1986-87 academic year,

Trinity University undergraduates (n=166) were asked: "In general,

do you consider yourself to be a `morning person' (11% so identified themselves),

an `afternoon person' (17%), an `evening person' (41%) or a `night owl'

(41%). Majors in the arts, humanities and social sciences were significantly

more likely to be "night people" than those majoring in business,

economics, and the natural sciences.

For your "Trivial Pursuit" files: Why is midday called

"noon"? Fasting Christians were permitted centuries ago a snack

at the ninth hour after sunrise, a time called "Nones," usually

occurred around 3 p.m. But the most devout got hungry and had an early

snack. In the 12th century, such fudging stabilized at midday and became

"noon."

NIGHT TIME

In "Night as Frontier" (American Sociological

Review,43,1979:3-22),

Murray Melbin developed the parallels between the colonization of space

and the colonialization of time, night-time that is. "Many of the

factors that stimulated expansion into the dark are the same as those that

led to expansion across the land. ...Demand push operates when over-population

and crowding begin to impel people toward new areas. That push is complemented

by supply pull, the lure of the untapped resources in areas beyond

established areas."

DAYLIGHT SAVINGS TIME

Do you know why it's hotter in the summer than in the winter? Because

in the summer we have an extra hour of daylight, which we take away in

the winter.

--Anonymous

Debates over daylight savings time continue around the world. Widespread

opposition in Mexico, for instance, postponed its nation-wide implementation

until 1996. Many viewed such alteration of their time as a exercise of

centralized power. When Colorado first experimented with Daylight Savings

Time newspapers were filled with hostile letters to the editor. One person

complained that the government had no business fiddling with "God's

time" and hinted that the principle of separation of church and state

had been violated. Another griped how the extra hour of sunlight was burning

up her yard (Chance, Paul. 1988. "Got a Minute?" Psychology

Today Nov.:59-60).

Blame our "Spring forward, Fall back" ritual on the Brits.

Although Benjamin Franklin toyed with the idea in a 1784 essay, credit

is generally given to William Willett, a British builder and astronomer,

who campaigned in 1907. Willet suggested that the clock be moved ahead

by 80 minutes in four 20-minute increments during the spring and summer

months. The benefits, he reasoned, would be extra time for recreation,

less crime, and higher energy savings as people would use less fuel for

lighting. But it took world war to finally put the time change into practice,

and even then it didn't stick. Congress adopted year-round daylight-saving

time for a two-year trial period that began Jan. 6, 1974. But it only lasted

one season, once again a victim of public complaints. From 1975,the number

of months falling to daylight-saving time was reduced until 1987, when

Congress passed an amendment to the Uniform Time Act that made daylight-saving

time run a full seven months.

THE SEVEN-DAY WEEK

In his The Seven Day Circle: The History and the Meaning of the

Week, Eviatar Zerubavel develops how the history

of the week is a story involving religion, holy numbers, planets, and

astrology--hence our shortened labels for Saturn Day, Sun Day, and Moon

Day (see the story of the origin of the seven-day week from

Bill

Hollon and from the National Institute of Standards and

Technology). Some numbers are

considered desirable, lucky, or holy in many nations. The number seven

is one of these. This is one reason why there are seven days in the week

(in fact, in many languages the word for week is synonymous with the word

for seven).

Much of our lives is centered and structured around a weekly pattern.

Indeed, as Pitirim Sorokin observed, the week is "one of the most

important points in our `orientation' in time and social reality."

As children, we learn the meaning of the weekend before we learn the meaning

of a month. There are clear phenomenological differences between Friday

time and Monday time; we are not biologically hardwired nor naturally triggered

to feel knotted stomachs on Sunday evenings. When Trinity University students

were asked what their favorite day of the week was, 25% said Thursdays,

37% said Fridays and 22% Saturdays.

Is it not the case that each day of the week has evolved to have

its own "flavor"? (see Global Psychics

page on superstitions associated with each week day) I've often thought about how

early Boomers may have been socialized toward such weekday distinctions. Consider, for

instance, the lessons of one of their most popular after-school television programs, "The

Mickey Mouse Club." Do you remember how the days went?

- On Mondays, Fun with Music Day, the sequence opens with Mickey playing

an upright piano. Realizing he has an audience, he leaps up and addresses

an unseen group of children:

Mickey: Hi, Mouseketeers!

Children: Hi, Mickey!

Mickey: Big doings this week - adventure, fun, music, cartoons, news -

Everybody ready?

Children: Ready!

Mickey: Then on with the show!

- For Guest Star Day on Tuesday, Mickey appeared once again playing

the piano. This time, it's a grand, and he's nattily attired in a tuxedo.

Mickey: Hi, Mouseketeers!

Children: Hi, Mickey!

Mickey: Got guests comin' and everything. Everybody neat and pretty?

Children: Neat and pretty!

Mickey: Then, take it away!

- Wednesday finds Mickey dressed as the Sorcerer's Apprentice from

Fantasia, riding onto the stage on a rambunctious flying carpet. It's interesting

to note in the dialogue that follows that Mickey refers to the day as being

Stunt Day, although it was actually Anything Can Happen Day.

Mickey: Whoa, boy! Whoa, steady! Hi, Mouseketeers!

Children: Hi, Mickey!

Mickey: Wednesday is Stunt Day, Mouseketeers, so hang on, anything goes!

Ya ready?

Children: Ready!

Mickey: Then let the show begin!

- For Thursday, Circus Day, Mickey is dressed in a band costume and

plays the slide trombone. This is the shortest of the introduction scenes.

Mickey: Hi, Mouseketeers!

Children: Hi, Mickey!

Mickey: Well, today is, ah, oh, ah...

Children: Circus Day!

Mickey: Right! Okay, Mouseketeers, all together now...

Children: On with the show!

- The final opening sequence is for Talent Round-up Day on Friday.

Mickey appears dressed as a cowboy, twirling a lariat as he speaks to the

audience.

Mickey: Yee-ee, Yee-ee! Hi, podners!

Mickey: This here's our roundup day, so you all pretty nigh ready?

Mickey: Sure enough!

Mickey: Let's get on with it!

Among the weekly rhythms (and myths of daily differences) we

find:

- rich

international folklore concerning each day's traits, such as how

individuals' temperaments are shaped by the day on which they

are born or how Fridays, because it was the day of Christ's crucifixion, are associated

with misfortune;

- a distinctive week cycle of births, whether

vaginal or cesarean, with Monday peaks and weekend troughs;

- weekly cycles of lethal heart attacks, with Mondays being the deadliest

day, according to a 1980 study reported by University of Manitoba researchers.

In their long-term follow-up study of nearly 4,000 men, they found that

38 had died of sudden heart attacks on Mondays while only 15 died on Fridays.

Further, for men with no history of heart disease, Monday was particularly

dangerous. While there were an average of 8.2 heart attack deaths for Tuesdays

through Sundays, Mondays were three times as lethal.

- weekly cycles of violent crime;

- in France, automotive lemons are referred to as "Monday cars;"

Certainly one driving force behind these weekly cycles is the rhythm

of working (or "week") days and days of the weekend. Speaking

of manmade times that have come to accrue a sense of "naturalness"

and to compartmentalize a very clear set of "appropriate" social

activities, the weekend is one of the most obvious.

Yet this special time for familial, religious, leisure, and consumptive

activities is a historically-recent creation. According to Witold Rybczynski

in Waiting for the Weekend, the Oxford English Dictionary finds

the earliest recorded use of the word in an 1879 English magazine. Battles

over the precise meaning of this time continue. Through the eighteenth

century when the workweek concluded on Saturday evenings, not only was

Sunday the only weekly "day off" but was to be a day of moral

restraint (no merriment please) and religious ritual. This was the legacy

of the Reformation and Puritanism; Sunday was the weekly holy day, a time

designed to displace Catholicism's numerous saints' and religious festival

days. But then there is the fact that work time and play time was more

blurred in the past, unlike their strict segregation nowadays. The workplace

featured a number of recreational activities. Rybczynski notes how trade

guilds often organized their own outings and singing and drinking clubs.

In 1926, Henry Ford closed all of his factories on Saturdays--not

to increase time for moral reflection or personal development but to increase

consumption. But it was not until the Great Depression that the two-day

weekend became firmly fixed, and that was to remedy the shortage of jobs.

THE MONTHS

Another Month Ends All Targets Met All Systems Working All

Customers Satisfied All Staff Eager and Enthusiastic All Pigs Fed and Ready

to Fly. --Entry in Weekly Schedule of New Zealand Symphony

Orchestra

Like the days of the week,

each month has a rich folklore tradition of associated

beliefs shaping the course of human activity. Take a look at the Les tres riches heures du Duc de Berry at the

Paris Webmuseum. Each month has its own portrait featuring the activities of the peasants and

aristocracy. Is it not interesting how varied the monthly activities are even for the

peasants, especially compared with nearly indistinguishable monthly activities of the

contemporary post-industrial "peasants" working in fast food franchises and

malls?

Like the days of the week,

each month has a rich folklore tradition of associated

beliefs shaping the course of human activity. Take a look at the Les tres riches heures du Duc de Berry at the

Paris Webmuseum. Each month has its own portrait featuring the activities of the peasants and

aristocracy. Is it not interesting how varied the monthly activities are even for the

peasants, especially compared with nearly indistinguishable monthly activities of the

contemporary post-industrial "peasants" working in fast food franchises and

malls?

For events associated with each day of the month in addition to material on Black,

Women's, and Lesbian and Gay History Months click here.

As portions of the day and week have taken on their own separate

meanings and activities, so too do we see differing rhythms of the month

(even though they are generally less significant to our lives than the

seasons in which they are grouped). There are, for example, times of the

month to pay bills or to summarize economic activities of the previous

four weeks.

ANNUAL SOCIAL CYCLES

In examining the natural rhythms of life,,

a number of seasonally-related phenomena were observed, such as:

- Since the turn of the century, wills are most frequently made in

the spring-in the months of April, May, and June.

- When examining college student reports of relationships concluding

with boyfriends and girl friends, Zick Rubin, Charles T. Hill and Letitia

Peplau found the large majority of breakups took place during May/June,

September, and December/January.

What annual social rhythms can you think of that cannot be accounted

for by biometeorological factors?

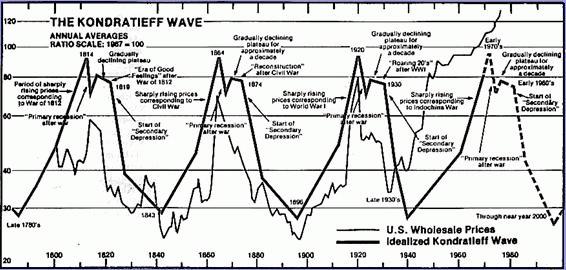

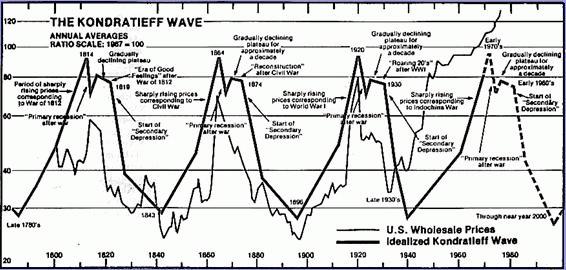

INSTITUTIONAL

RHYTHMS

Here we consider such rhythms as the liberal-conservative cycles

studied by political scientists, the boom-bust cycles detected by economists,

the rural-urban migration cycles measured by demographers, and the cycles

of nostalgia and utopianism analyzed by sociologists.

- The Longwave and

Social Cycles Resource Centre

- Wm. Murray's

Time Page

- US Economy: Business

Cycle Indicators

- The Coming

Collapse

- Foundation For The

Study Of Cycles

RHYTHMS OF THE "CONJUNCTURE"

In Civilization and Capitalism 15th-18th Century: Vol. III The

Perspective of the World, Fernand Braudel develops the various endless

periodic movements shaping human life. The combination of these movement

forms what he calls the conjuncture, affecting economics, politics,

demographics, crime, artistic movements, and popular culture. Of these

he writes:

These conjunctures, just like the tide, carry on their backs the shorter

movements of more short-term waves. Each can be studied during its upward trend,

peak and crisis, and downward trend, and then how its phase synchronizes with

the other social movements.

For instance, historians have observed how economic declines can encourage

cultural explosions. In describing the creative surges spawned by the collapse of cultures,

Harold Innis writes:

With a weakening of protection of organized force, scholars put forth

greater efforts and in a sense the flowering of the culture comes before

its collapse. Minerva's owl begins its flight in the gathering dusk not

only from classical Greece but in turn from Alexandria, from Rome, from

Constantinople, from the publican cities of Italy, from France, from Holland,

and from Germany (Innis, 1951:5).

In speaking of the surge of creativity in war-ravaged Lebanon, Charles

Rizk, president of Lebanon's state-run television system, reflected in

1982: "A political shock is always pregnant with cultural achievement.

When simply walking down the street becomes a matter of life and death,

people start to ask themselves very fundamental questions. And what is

culture if not expressions of man's questioning himself about his ultimate

destiny"?

HOW SOCIAL TIME IMPINGES ON THE INDIVIDUAL

So how are these various rhythms experienced by the individual?

- they provide a sense of temporal order, giving people a framework

for making social life predictable. As Mark Twain put it: "Time is

nature's way of preventing everything from happening all at once."

The antithesis: the feelings of suspension, of being somehow "lost"

during a vacation when without a schedule. (For other humanistic descriptions

see Patek Philippe's "Concerning

Time.")

- contributing to time's ability to shape a sense of social order

are the temporal boundaries marking the beginning and conclusion of a social

performance. Enter, for instance, the power of temporal deadlines, which

demand not only the culmination of social projects but, like the life reviews

of those on their deathbeds or students' crammings for final examinations,

also demand summative reflections as to the net meaning of the entire social

enterprise. Individuals are classified in terms of how they react to such

timetables. Among the more notable types are the procrastinators

.

- time is the container of not only our social actions but our emotions

as well, evidenced in our temporal feeling rules. The holiday season, for

instance, can often elicit depression among those who sense that they are

supposed to feel joyous and yet feel they aren't.

- out of the normal rhythms of various social activities arise socially

expected durations. When durational expectations are violated, individuals

experience a form of temporal frustration called impatience.

- temporal commitment = social commitment. To what extent does the

time individuals spend in a particular role shape their self-understanding

of what they think are their most important social activities? "I'm

spending ten hours a day doing this-- it must be really important to me."

- temporal oppression. The greater the social control the more

likely the timing of one's activities are programmed by society. In Erving

Goffman's "total institutions," such as prisons and nursing homes,

the timing even of such biological processes as eating, sleeping, and defecating

is socially dictated.

- temporal conflicts. Because of our numerous role obligations, many

of which make potentially limitless temporal demands ("Acme Widgets

expects you to give 110%), individuals often feel they are role failures,

feeling guilt and stress as a result. The premier example is the working

mother, who is torn in two directions by the demands for full-time commitment

by both her children and employer.

- temporal scarcity. One consequence of temporal conflicts is the

growing sense of time's finiteness. The lack of time seems to rank among

Americans' top concerns, echoed in a 1989 Time magazine cover story,

"How America Has Run Out of Time," wherein cited were the results

of a Harris survey showing the amount of leisure time enjoyed by the average

American having shrunk 37% since 1973 and how, over the same period, the

average workweek including commute time having increased from under 41

to nearly 47 hours.

SPECIAL CLOCKS--GAUGING

THE SOCIAL ORDER

Dava Sobel's Longitude (1995) is an engaging story of how

the Navigation

Problem, that is knowing one's longitude, was ultimately solved by thinking

in time. If one always knows what time it is at some agreed-upon zero-meridian

(Greenwich, England, where else?) as well as one's own time (by setting the

local clock to noon when the sun was directly overhead), then the following

calculation can be made: one hour of difference in time equals 15 degrees of

longitude separation.

Dava Sobel's Longitude (1995) is an engaging story of how

the Navigation

Problem, that is knowing one's longitude, was ultimately solved by thinking

in time. If one always knows what time it is at some agreed-upon zero-meridian

(Greenwich, England, where else?) as well as one's own time (by setting the

local clock to noon when the sun was directly overhead), then the following

calculation can be made: one hour of difference in time equals 15 degrees of

longitude separation.

This idea of knowing where we are by using time has evolved considerably,

from measuring where we personally are in space to where we are both in

our personal and collective endeavors. There are, for instance, the micro-measures

of scheduled time: At Oxford's slacks factory in Monticello, Ga., a new

system clocks every worker's pace to a thousandth of a minute. The workers,

mostly women, are paid according to how their pace compares with a factory

standard for their job. An operator who beats the standard by 10% gets

a 10% bonus over her base rate. If she lags 10% behind the standard, she

has 10% knocked off her wages.

In 2007, the American Civil Liberties Union first wound its “Surveillance Society Clock” to countdown the extinction of privacy. It was set at 11:54 p.m. Theirs was not the first symbolic time piece to gauge where we are in history. It joins a myriad of clocks marking social change:

- Since 1947 the Bulletin

of the Atomic Scientists has included a "doomsday clock," ticking a countdown

to nuclear oblivion. Between 1947 and 1994, the hands have been moved thirteen

times.

- The Digital Doomsday clock--an

"indicator of the threats to cyber-rights"

The Census Bureau

has its population clocks. What time is it? As of November 2007,

local

time is half past 303 million, thank you. Another timepiece of the Bureau is its

World

POPClock.

The Census Bureau

has its population clocks. What time is it? As of November 2007,

local

time is half past 303 million, thank you. Another timepiece of the Bureau is its

World

POPClock.

- The

Earth Clock tallies population statistics, CO2 emissions, species

extinctions, barrels of oil pumped, and U.S. garbage production

- Peter Russell's Spirit of Now

World Clock,

including demographics, energy consumption, military expenditures, and victims

of noncommunicable and infectious diseases

- The Teen Pregnancy

Clock.

Every 26 seconds another American adolescent becomes pregnant; every 56

seconds an adolescent gives birth.

- The AIDS clock

tallies HIV infections world wide.

- The Census Bureau also

brings you its Economic Clock.

- The World Stats clocks, or Worldometers,

giving real-time statistics on education, business, the world's food supply,

the environment, and more.

The

Military Spending Clock

--each minute the U.S. was spending nearly $590,000 before this timepiece was

unplugged in early 2003. Veterans for Peace, however, have a

Cost of

the War in Iraq clock

- The Drug War Clock

tallies state and federal expenditures on the war on drugs, about $600 per second in 2003

- The Tobacco Treaty "Death Clock" started ticking in October

1999, one of several death

clocks on the web

- The United Nations

Development

Program maintains a Poverty Clock, tallying the increase since January

17, 1996, in the number of people who live on less than one dollar a day

around the world. Time as of November 11, 1997:

.

Time in early 2003? Unknown. Clock unplugged.

.

Time in early 2003? Unknown. Clock unplugged.

- The National Debt Clock--as

of September 24, 2008 it's $9,790,033,347,303.75!

- Bill Gates Personal Wealth Clock.

- Prisonsucks.com features an Incarceration Clock

- Among the digital timepieces of the Millennium

Institute are those marking the number of species becoming extinct

each day and the number of years until one-third will be lost.

- Digital Doomsday is a

"digital indicator of the threat to cyber-rights everywhere."

- In 1993 there appeared in Times Square an electronic billboard that

tallies the number of gun-related homicides. On the other hand, there is

the WWW Gun Defense Clock clicking

off the number of times "an American firearm owner uses a firearm in

defense against a criminal."

- In Los Angeles: "Smoking Deaths This Year and

Counting"

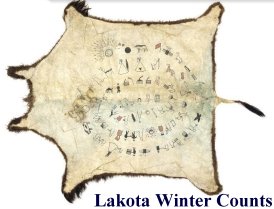

CALENDARS

I've been on a calendar, but never on time. --Marilyn

Monroe

One basis of social life is the predictability of others' actions.

One way that this is obtained is through the social creation of regulated

rhythms and temporal boundaries for specific social activities. From the

perspective of individual actors, these periods are understood (and internalized)

to be "appropriate times;" culture and society specify not only

how things are to be done but when.

This is the essence of what Jeremy Rifkin refers to in Time Wars

as "calendrical power." These specified times not only specify

the timings of various activities but also become the bases of in-group

solidarity and identity. As Evitar Zerubavel concluded in "Easter

and Passover: On Calendars and Group Identity" (American Sociological

Review 47 [April 1982]:288),

The calendar helps to solidify in-group sentiments and thus constitutes

a powerful basis for mechanical solidarity within the group. At the same

time, it also contributes to the establishment of intergroup boundaries

that distinguish, as well as separate, group members from

"outsiders."

Not surprisingly, changes in group solidarities have historically

brought demands for calendrical reform, as can be seen in the Calendar

Reform Homepage.

NEW YEARS

As is the case for all social endings,

the conclusion of a calendrical year brings reflection, comparison, and

anticipation. Increasingly it seems there the "Best Ofs" and

"Worst Ofs." The year's end brings the National League of Junior

Cotillions list of the 10 best- mannered people of the year. Newspaper

articles of late December and early January feature box scores of crime

rates, rainfall totals, and host of economic measures. And there are "milestone"

summaries of who of note had died.

As is the case for all social endings,

the conclusion of a calendrical year brings reflection, comparison, and

anticipation. Increasingly it seems there the "Best Ofs" and

"Worst Ofs." The year's end brings the National League of Junior

Cotillions list of the 10 best- mannered people of the year. Newspaper

articles of late December and early January feature box scores of crime

rates, rainfall totals, and host of economic measures. And there are "milestone"

summaries of who of note had died.

- Chinese

New Year

SPECIAL DAYS

- Teresa Ruano's "Ancient Origins of the Holidays"

- Yahoo's

directory of Holidays and Observances

- Groundhog Day--Punxsutawney, PA

- April Fools on the

Net

Return to Times of Our Lives Index Page

Return to Times of Our Lives Index Page

It's hard to believe that only about a century ago most towns in

this country had their own time. The hands of the clock in the town square

would be synchronized with cosmos, "high noon" being established

when the sun being at its highest point for the day. But owing to technological

innovations (particularly the railroads, whose schedules of arrival and

departure times required greater temporal uniformity) and enhanced interdependencies

between social members, "standard time" emerged. This replacement

of local time- reckoning with supralocal standards of time marked a fundamental

change in our relationship to time: human activity was to be increasingly

oriented to social as opposed to natural times. Take a look at WebExhibits

Calendars Through the Ages

for "the fascinating history of the human endeavor to organize our

lives in accordance with the sun and stars," and Simon K. Chung's

Chronology

for an illustrated history of the clock in the West.

It's hard to believe that only about a century ago most towns in

this country had their own time. The hands of the clock in the town square

would be synchronized with cosmos, "high noon" being established

when the sun being at its highest point for the day. But owing to technological

innovations (particularly the railroads, whose schedules of arrival and

departure times required greater temporal uniformity) and enhanced interdependencies

between social members, "standard time" emerged. This replacement

of local time- reckoning with supralocal standards of time marked a fundamental

change in our relationship to time: human activity was to be increasingly

oriented to social as opposed to natural times. Take a look at WebExhibits

Calendars Through the Ages

for "the fascinating history of the human endeavor to organize our

lives in accordance with the sun and stars," and Simon K. Chung's

Chronology

for an illustrated history of the clock in the West.

Dava Sobel's Longitude (1995) is an engaging story of how

Dava Sobel's Longitude (1995) is an engaging story of how

The

The