IMAGES ACROSS

CULTURES AND

TIME

"At birth we cry; at death we see

why."

--Bulgarian proverb

"Birth is the messenger of

death."

--Syrian proverb

Like the climatologists who so eagerly awaited the

close-up photographs of Jupiter and Saturn in order to understand the atmospheric

dynamics of earth, we need cross-cultural comparisons in order to comprehend

ourselves. "Death" is a socially constructed idea. The fears,

hopes, and orientations people have towards it are not instinctive, but

rather are learned from such public symbols as the languages, arts,

and religious and funerary rituals of their culture. Every

culture has a coherent mortality thesis whose explanations of death are so thoroughly

ingrained that they are believed to be right by its members. It is here

assumed that any broad-scale change in the relationships between the living

is accompanied by modifications of these death meanings and ceremonies.

The reverse may well also be true: Would there be a rash of suicides if

it were to be conclusively verified scientifically that the hereafter is

some celestial Disneyland? And what if the quality of one's experiences

there was founded to be based on the quality of one's life?

- Annwfn: The Mythology and Folklore of Death from

The City of the Silent

- H.C. Yarrow's 1881 "Introduction to the Study of Mortuary Customs

Among the North American Indians"

- Myth in Death and Dying

- Euphemisms for Death

-- both physical and symbolic (with a dash of humor)

If you were to parachute down into some exotic culture,

precisely how would you classify its death

ethos (or death

system), the entire veil of order and meaning that societies construct

against the chaos posed by death?

Anthropology provides various strategies. Among the cultural indicators to be the

considered would be:

- nature of their beliefs toward the meaning of life,

death and the hereafter;

- funerary rituals and strategies

for body disposal;

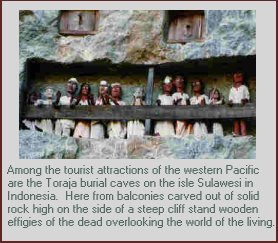

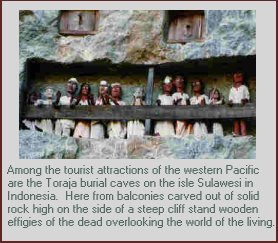

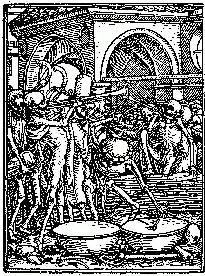

- as illustrated in the image on the right, the physical and

symbolic boundaries between

the worlds of the living and the dead;

- the perceived role of the dead on the affairs of the

living;

- whether the dying process is a public or private event;

- the degree of social stigma attached to those dying,

dead, or bereaved;

- orientations toward and rates of suicide, murder (perhaps

broken into categories of infanticide, genocide, etc.), and abortion;

- centrality of social goal of death prevention and

avoidance;

- the death socialization of children (including death

themes in children's stories and games) and their involvement in funerary

ritual;

- the taboo status of the topic of dying and death in

everyday discourse;

- the language used regarding death (have you noticed

how often in American culture we employ euphemism to describe death and

yet how we use death metaphors to describe non-death-related matters (e.g.,

their team killed ours last night; if you don't work hard you will be terminated

or axed);

- and the nature and conceptions of death in the arts.

In considering the various facets of death ethos

cross-culturally,

Arnold Toynbee ("Various Ways in Which Human Beings Have Sought to

Reconcile Themselves to the Fact of Death," 1980) and others have

developed typologies of orientations toward life and death:

- Cultures can be death-accepting, death-denying or

even death- defying. In the death-defying West, the strategies for salvation

have historically included activism and asceticism. In the East, the strategies

have often been more contemplative and mystical.

- Death may be considered either as the end of existence

or as a transition to another state of being or consciousness. For Buddhists and Hindus, the

arch-ordeal envisioned is not death but rather the pain

of having to undergo another rebirth. It is the end of rebirths that is

their goal, not the end of death, which is the goal of Christianity.

- Considering the two previous dimensions, it should

be evident that death can be viewed as either sacred or profane, a state

or process perceived either to be sacrosanct or polluting for the living.

- Where there is some immortality conception, it can

either be personal or collective. In the West, post-death conceptions typically

involve the integrity and continuity of one's personal self. In the East,

the ultimate goal is often an undifferentiated and impersonal oneness with

the universe.

- Cultures have taken hedonistic and pessimistic orientations

toward life in facing the inevitability of death, such as taking an "eat,

drink, and be merry for tomorrow we may die" approach to life.

- The American notion of life being what's objective

and concrete while the hereafter has an illusory quality is far from being

universal. The Hindus, for example, handle the problem of death by viewing

life as the illusion and the realm between reincarnations as that which

is objective. Hence, for many in Eastern cultures the primary concern is

to avoid rebirth by extinguishing one's self-centeredness (thereby, for

the Buddhists, being absorbed into an impersonal, collective oversoul),

while in much of the West, this concern is to obtain as high a quality

of personal existence as is possible in the here-and-now.

Before getting too carried away with this classification

business, it's worth reflecting on the value of the enterprise. Say that

we have for each dimension of a cultural death system a set of mutually

exclusive and totally exhaustive categories such that each culture can

be pigeon-holed into one and only one, what then? So what?

The first step might to see how these various categories

cluster together. For instance, are there patterns in the way beliefs in

an afterlife correlate with cultural/personal orientations toward abortion

or euthanasia? Is cultural thanatophia related to cultural gerontophobia--

in other words, do death fears lead to fears of growing old? This question

brings us to the second and most important step: how orientations toward

death relate to orientations toward life.

The first step might to see how these various categories

cluster together. For instance, are there patterns in the way beliefs in

an afterlife correlate with cultural/personal orientations toward abortion

or euthanasia? Is cultural thanatophia related to cultural gerontophobia--

in other words, do death fears lead to fears of growing old? This question

brings us to the second and most important step: how orientations toward

death relate to orientations toward life.

At issue is the relationship between a culture's death

ethos and its life ethos, the latter described by Clifford Geertz (The

Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays, 1973:127) as "the

tone, character, and quality of their life, its moral and aesthetic style

and mood; ... the underlying attitude toward themselves and their world

that life reflects." For instance, what facets of their death ethos

lead the Spanish to disdain the life insurance industry?

Public distaste for life insurance has left the industry in Spain

more malnourished than in any other major Western European economy. Only

nine of every 100 Spaniards have life insurance, for an estimated annual

per capita premium cost of $10.20. That compares to $154 in Western Europe

and $230 in the U.S....

Some examples of what insurance sales people must contend with in

Spain:

- The mother of a drowned fisherman flatly refused to accept his death

benefits from an insurance company.

- A village priest railed against the trade, asking, `Who but God

can insure life?'

- Last month, the Socialist General Union of Workers denounced Spain's

state-controlled telephone company for providing `scandalous' life insurance

and pension coverage for 160 top executives.

--Ana

Westley. 1984. "Spaniards Distaste for Life Insurance Leave the Industry There Languishing."

Wall Street Journal, March 29:28

"The fundamental law of the social order [is] ... the progressive

control of life and death."

-- Jean Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, p.172

A major tradition in the study of death across cultures

and time has been to demarcate distinctive death epochs in Western history.

The most notable illustration is Philippe Ariès's The Hour of Our Death,

wherein developed are five models of death that have succeeded one another

of the past millennium:

- tame

death. Here death was considered a process that

was both familiar and near, featuring a simple public and ritualistic ceremony

largely controlled by the dying person and for which friends and family,

including the children, were present.

- death of self. With the

devastating

Black Plague,

increasing individualism, and the weakening of traditional community ties

(with perhaps a growing collective sense of the demise of the old feudal

order), dying became the time when the true essence of oneself was assumed

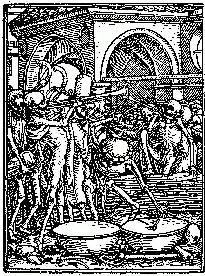

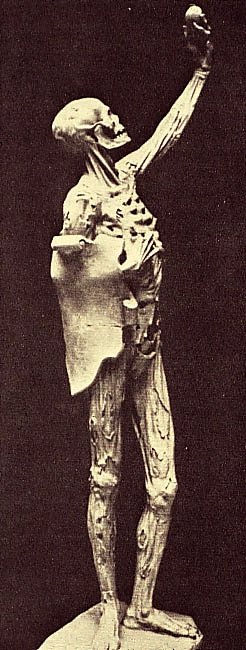

to be revealed. The macabre iconography

of this era (for more images see As

I am so thou shalt be) often featuring partially decomposed cadavers with maggots

and snakes, has been variously interpreted. Perhaps it was an era of a

renewed appreciation of life and its possibilities. Indeed, a life was

no longer subsumed within the collective destiny of the group (hence the

fading of the vendetta system, as kin members were no longer seen to be

functionally equivalent, but became viewed as a biography, each moment

of which would be judged by Christ after death. It was at this time that

people concerned themselves with their distinguishing characteristics,

began writing autobiographies, became interested in drama and in the

distinctions between roles and their occupants, and postulated the existence

of an internal inner self. To assist in individuals' mastery of their own

deaths, an instructional manual on the art of dying, entitled Ars

Moriendi, was to be a best seller for two centuries. Other resources: University of Chicago's "The Plague: Buboes,

Masses and Kinases; Patrick Pollefeys' "As

I am so thou shalt be;" and Tom Bacig's "The

Black Death" page.

- remote and imminent death. With

increasing secularization and the Enlightenment's rise of science, by the 1700s death came

to be viewed as some rupture or a break with life rather than as part of

a continuum, an event no longer seen as a supernatural experience, a matter better put out of mind.

- death of the other.

With changes

in the nature of familial bonds during the 1800s, death fears shifted from

the death of oneself to the death of one's significant others. Death came

to be romanticized. For insights into the Victorian era see Dan

Meinwald's "Memento Mori: Death and Photography in Nineteenth Century

America" (and

Memento

Mori from thanatos.net) "Responses

to Death in Nineteenth Century America," Death--the

last taboo: Victorian Era (from Australian Museum online), and the Victorian

Funeral and Mourning Etiquette page.

- invisible death. With

the increasing

privatization of death and the institutionalization of the dying, by the

mid-1900s death denial was to become the reigning orientation. From the

natural sciences came the perspective that, in the broad scheme of things,

individuals' lives and deaths are inconsequential.

FORCES

CHANGING CULTURAL DEATH

ETHOS

Factors associated with these changes in cultural death systems include:

Factors associated with these changes in cultural death systems include:

- Changes in social structure.

The challenge of death is most extreme within small, primitive societies

where famine, disease, or war could lead to the destruction of the entire

group. As populations increased the need for greater social coordination

and control gave rise to large bureaucratic structures. Within these, roles

became more important than their replaceable occupants. This idea of being

disposable and replaceable is, of course, a major assault on individuals'

sense of dignity and esteem, making their deaths relatively insignificant

events.

- Changes in bonds between people:

Urbanization brought a fundamental shift in the "social gravity"

binding a people. For most of human history this force of social attraction

entailed the intimate bonds between homogeneous residents of small communities.

Here individuals knew one another as whole persons, and they grew old together.

Here the death of one of the community's members could not be ignored for

the loss was genuine. It had to be ritually marked by community-wide outpourings

of grief in order to assist the stricken group to reestablish and reintegrate

itself.

Nowadays this social gravity features the impersonal

bonds linking heterogeneous and interdependent strangers within large urban

areas. Interpersonal no longer are based on mutual affection but rather

on the achievement of complementary goals. Total selves are irrelevant

to most social interactions; we now interact toward most others solely

on the basis of the roles that they play. Here the scope of grief is limited

to the family and friends of the deceased, who are given but a few days

off from work before being expected to return a social system usually unaffected

by the death.

- Changes in the conception of

selfhood.

The contemporary self that faces death is considerably different from the

selves of the past. Nineteenth century selfhood was, as was the case through

most of the past and remains the norm in many cultures, more collectivist

in orientation. Personal extinction did not hold the terror it currently

does because the ultimate social unit--namely, one's tribe or clan--continued

to survive despite the singular deaths of its members.

As Roy Baumeister develops in The Meanings of Life

(1991), with increasing individualism and value-relativism, the quest

for identity and self- knowledge has become people's primary source of

life meaning. This has made the self more vulnerable to death as death

now takes away both life and what gives it value.

In addition to these transformations in the world of

the living, the American death ethos also changed because of the following

trends in the nature and distribution of death.

- Changes in who dies--From youth

to the elderly as the culture's death lepers. One has but to look at the

demographics of developing societies to see where we once were. In civilization's

earliest period, women's average life span may have been less than 28 years

and infant mortality as high as 75 percent. The connection between death

and childhood largely remained in this country through the eighteenth century.

In Puritan New England,

where only 6 in 10 children reached adulthood, parents usually sent their

offspring away to the home

of relatives or friends supposedly as a method of discipline. In reality

this practice probably arose to prevent the death of a child from causing

parents too much emotional pain, for which reason we now send our infirm

elderly to nursing homes. Nowadays, so relatively rare have childhood deaths

become that the parental grief occasioned by stillbirths and miscarriages

may be relatively equal to the parental grief of the past following the

deaths of young children.

Indeed, death has become the province of the elderly,

with nearly 80 percent of all deaths in this country occurring to individuals

over 65 years of age. The assumption that citizens will live to see their

biblical three score and ten years is reflected in a new statistic of the

federal government: YPLL, "years of potential life lost" when

people die before the age of 65. In many ways the American "problems"

of old age are bound-up with the "problems" of dying. Gauging

from their increasing segregation from other age groups, the elderly are

our culture's "death lepers."

- Changes in when we die--From

premature to postmature deaths. While the death ethos of historical societies

was shaped by the prevalence of unanticipated and premature deaths, death

now typically occurs upon the conclusion of full, completed lives. Instead

of dying with one's proverbial "boots on," death increasingly

occurs among those already disengaged from the social mainstream. When

death does occur prematurely, such as when a teenager is murdered or a

young father dies in an auto accident, it most often occurs because of

manmade (hence avoidable) causes.

- Changes in how we die--From Sudden

to Slow-motion Deaths. There have been profound changes in the very quality

of death. Owing to innovations in public sanitation and medical technology,

death now typically occurs in slow-motion due to degenerative diseases,

often exhausting the resources and emotions of families. Because of our

tendency to depersonalize those most likely to die, slow-motion deaths

mean that individuals must now die a number of social mini-deaths before

actually physiologically expiring.

- For thoughts on role

of microbes shaping course of history see Jared Diamond's "Why Did Human History Unfold

Differently on Different Continents for the Last 13,000 Years?"

-

Michael Bathrick and Charles Niquette's Bibliography of Funeral and Burial

Practices (1994)

- Yahoo's Society

and Culture:Death

- The

Webster's collection of links to cross-cultural images of death

- The

Egyptian Book of the Dead

- Funeral

Beliefs in Roslea--a traditional Irish wake

- Unbelieveable

Events In Bali : Cremation Processing

A CASE STUDY: THE MEXICAN DEATH

SYSTEM

Given the proximity of the United States to Mexico and the fact that

Mexican Americans comprise one of the fastest-growing groups in America,

it's worth reflecting on their traditional death ethos and its impact on

the American death system.

Poet Octavio Paz writes that Mexicans are "seduced by death."

To the American eye, their culture is steeped with morbidity: there's the

life-death drama of the bullfight;

the Day

of the Dead or Dia

de los Muertos observances and folkart,

replete with skeletons and bloody crucifixes; the Mummy

Museum in Guanajuato; and the pervasive death themes within the works

of such muralists as Orozco,

Jose Guadalupe

Posada,, Diego

Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. This death-rich cultural tradition

reflects the fusion of Indian and Catholic legacies, the former includes

the heritage of human

sacrifices practiced by the Mayans

and Aztecs.

Such phenomena, despite their surface appearances, are not necessarily

features of a death-accepting culture. In a country historically marked

by unstable, corrupt, authoritarian regimes, it is interesting to note

how honoring the dead has given individuals license to comment on the living.

There is a satirical magazine that is published in even the smallest hamlet

that owns a print shop. This publication, called LA CALAVERA (the

skull), is filled with satirical poetic eulogies of living members of the

community, ranging from the town drunk to the mayor's wife. The famous

skeletal caricatures

of Posada served to raise political consciousness in Mexico before

the revolution. In sum, it is not simply the case that life is so miserable

that death is preferable. In fact, the festive death rituals are neither

positive nor negative, but rather "an existential affirmation of the

lives and contributions made by all who have existed...(and) the affirmation

of life as the means for realizing its promise while preparing to someday

die" (Ricardo Sanchez, 1985, "Day of the Dead Is Also about Life,"

San Antonio Express-News, Nov.1). They reflect not only Mexico's

cultural heritage but also its fusion with economic and political exigencies.

RELATED RESOURCES:

- Alexis

Ciurczak and Jose Rangel's Day of the Dead Page

- Ricardo Salvador's "What do Mexicans celebrate on the Day of

the Dead?"

- Catherine

Lavender's "El dia de los muertos" page

THE DEATHS OF CIVILIZATIONS

In a macro sense, death is the fate of not only humans but of all human creations.

See the Annenberg/CPB Project Exhibition Collapse: Why do

civilizations fall?

DEATH AND THE ARTS

It is when one first sees the horizon as an end that one first begins

to see... Ends are the hardest things in the world to see--precisely because

they aren't things, they are the ends of things. And yet they are wonderful.

What would life be without them!...if we didn't die there would be no works--not

works of art certainly, the only ones that count. ...Death is the perspective

of every great picture ever painted and the underbeat of every measurable

poem...

--Archibald

MacLeish

Certainly one realm of indicators of cultural death

conceptions is to be found in the arts. Through music, poetry, or paintings

of death we see not only conceptions of death but the cultural styles with

which the event is anticipated and met. Also revealed is a people's sense

of themselves. Art is one sure defense against time, against that dumbfounding

piece of information that life has a temporal end.

- "The Dance of Death"--artwork

and essays by artist Ian Breakwell and anatomist Bernard Moxham to encourage "today's

post-modern generation to confront mortality"

- The

Webster--"Death in Articles, Arts, Literature and Stories" section

- Women and

Death:

an anthrology of women's poetry

DEATH IN POPULAR CULTURE

The first month of 2006 brought several curious news items. Exhibit 1, on the right,

even received coverage in the New York Times. By playing dead, the

website owner "hopes to attain a modest form of immortality."

The website had a third of a million hits in its first three weeks.

The first month of 2006 brought several curious news items. Exhibit 1, on the right,

even received coverage in the New York Times. By playing dead, the

website owner "hopes to attain a modest form of immortality."

The website had a third of a million hits in its first three weeks.

Exhibit 2 was carried in the Los Angeles Times: Paula Thomas's "new

neo-Gothic" line of skull-covered garments. Writes Booth Moore, "Sure,

skulls are everywhere (on Vans sneakers, on Lucien Pellat-Finet cashmere

sweaters and in Luella Bartley's forthcoming line for Target). ... But Thomas' designs

are subtle enough to make fans out of the most refined women"

("The name on everyone's hips," Jan. 25, 2006).

Return to Kearl's Death Index

Return to Kearl's Death Index

The first step might to see how these various categories

cluster together. For instance, are there patterns in the way beliefs in

an afterlife correlate with cultural/personal orientations toward abortion

or euthanasia? Is cultural thanatophia related to cultural gerontophobia--

in other words, do death fears lead to fears of growing old? This question

brings us to the second and most important step: how orientations toward

death relate to orientations toward life.

The first step might to see how these various categories

cluster together. For instance, are there patterns in the way beliefs in

an afterlife correlate with cultural/personal orientations toward abortion

or euthanasia? Is cultural thanatophia related to cultural gerontophobia--

in other words, do death fears lead to fears of growing old? This question

brings us to the second and most important step: how orientations toward

death relate to orientations toward life.

Factors associated with these changes in cultural death systems include:

Factors associated with these changes in cultural death systems include:

![]()

The first month of 2006 brought several curious news items. Exhibit 1, on the right,

even received coverage in the New York Times. By playing dead, the

website owner "hopes to attain a modest form of immortality."

The website had a third of a million hits in its first three weeks.

The first month of 2006 brought several curious news items. Exhibit 1, on the right,

even received coverage in the New York Times. By playing dead, the

website owner "hopes to attain a modest form of immortality."

The website had a third of a million hits in its first three weeks.![]()