Arthur Koestler, noted author and founder of Exit,

wrote before his own suicide: "If the word death were absent from

our vocabulary, our great works of literature would have remained unwritten,

pyramids and cathedrals would not exist, nor works of religious art-and

all art is of religious or magic origin. The pathology and creativity of

the human mind are two sides of the same medal, coined by the same mintmaster"

(1977).

Arthur Koestler, noted author and founder of Exit,

wrote before his own suicide: "If the word death were absent from

our vocabulary, our great works of literature would have remained unwritten,

pyramids and cathedrals would not exist, nor works of religious art-and

all art is of religious or magic origin. The pathology and creativity of

the human mind are two sides of the same medal, coined by the same mintmaster"

(1977).

According to Franz Kafka, "Man cannot live without

a continuous confidence in something indestructible within himself" (Choron,

1964:15). In other words, the will

for immortality is a central drive of the human primate--perhaps even more

so nowadays in postmodern cultures where an increasing proportion of the

population not only survives into old age but reaches Maslow's

need for transcendence. For an inventory of human envisionments of an

afterlife see the Life

After Death Database. Five cultural

strategies have been identified by which such psychological needs for indestructibility

have been addressed (Morgenthau, 1967; Shneidman, 1973; Lifton, 1979; Kalish,

1985): the biological, religious, creative, natural and mystic modes.

The biological mode involves one's genetic immortality,

which provides a sense of continuity with one's ancestors and descendants.

Bertrand Russell, in discussing this aspect of parenthood, writes: "...there

is an egoistic element, which is very dangerous: the hope that one's children

may succeed where one has failed, that they may carry on one's work when

death or senility puts an end to one's efforts, and, in any case, that

they will supply a biologic escape from death, making one's own life part

of the whole stream, and not a mere stagnant puddle without any overflow

into the future" (cited in Shneidman, 1973:47-48).

Developments in stem

cell research have certainly enhanced hopes for one's own biological

immortality. Imagine being able to grow such spare body parts as new brain

or muscle cells, skin, hearts or lungs, or being able to cure such ailments as

Alzheimer's Disease, Parkinson's, leukemia, spinal-cord injuries, multiple sclerosis,

or blindness. (See site of the American

Association for the Advancement of Science Report on Stem Cell Research.)

Unfortunately the most programmable of stem cells come from

human embryos and fetuses, which has put this line of research into the crosshairs

of the anti-abortionists. (See the National Bioethics Advisory Commission's

"Ethical Issues in Human Stem Cell

Research.") Also enhancing the prospects for biological

immortality are developments in DNA preservation, which has now become a

business with such players as Genternity

LLC, whose website includes the thought "If the idea of physical

immortality appeals to you, Genternity provides the only scientifically feasible

means. On the other hand, regardless of how you perceive the idea of

physical immortality, to reject the option of DNA preservation is to

deliberately decide, once and for all, to discard the individual's unique

blueprint."

- Let Lazaron BioTechnologies save the DNA of your favorite pet for future cloning. Genetic Savings and Clone, the nation's first all-inclusive pet cloning enterprise,

now finds itself in competition with RePet and

others in the pet resurrection business. And why, ask the folks at the Human

Cloning Foundation, does just Fido get

cloned? One can also become

involved in the Raelian Revolution and be

shown a philosophy that links UFOs with personal cloning. For Americans' attitudes toward

human cloning see Bernice Kanner's

"Are You Normal? Human Clones." Other rich resources

include Human Cloning:

Religious Perspectives from the May, 2001 Pew Forum on Religion and Public

Life, the Scientific

and Medical Aspects of Human Reproductive Cloning (2002) from the National

Academy Press, and Human

Cloning and Human Dignity: An Ethical Inquiry (2002) from The

President's Council on Bioethics.

The religious mode entails the eternal life of the

believer, whether obtained through resurrection,

reincarnation

(see also the homepage of Reincarnation

International), metempsychosis,

or some other form of rebirth

(latest twist: Christians

For the Cloning of Jesus). Perhaps to this list we should add belief in Transhumanism, which views

aging and death as surmountable barriers to "total self-transformation and personal

freedom." Of course, what could be better than living forever, eternally remaining

oneself in some cosmic Disneyland realm? As developed in "You

Never Have to Die!", Americans are not only among the world's

firmest believers in an afterlife but they are quite optimistic about what

this existence holds. This is not to deny that there

are the detractors, that there is not a shred of scientific evidence

to support belief in the existence of any other dimension(s) of reality

beside the physical wherein the dead reside. Further, there are profound

conceptual difficulties with the heaven construct, as Michael

Martin develops in "Problems with Heaven."

The religious mode entails the eternal life of the

believer, whether obtained through resurrection,

reincarnation

(see also the homepage of Reincarnation

International), metempsychosis,

or some other form of rebirth

(latest twist: Christians

For the Cloning of Jesus). Perhaps to this list we should add belief in Transhumanism, which views

aging and death as surmountable barriers to "total self-transformation and personal

freedom." Of course, what could be better than living forever, eternally remaining

oneself in some cosmic Disneyland realm? As developed in "You

Never Have to Die!", Americans are not only among the world's

firmest believers in an afterlife but they are quite optimistic about what

this existence holds. This is not to deny that there

are the detractors, that there is not a shred of scientific evidence

to support belief in the existence of any other dimension(s) of reality

beside the physical wherein the dead reside. Further, there are profound

conceptual difficulties with the heaven construct, as Michael

Martin develops in "Problems with Heaven."

However, even

if personal immortality or absorption into some collective oversoul are

not possibilities, there are technological strategies for transcending death: living

as long as possible, being preserved at the moment of death and then

being scientifically resurrected (see Cryonics

Institute, which includes the full text of the book "that started the

cryonics movement," Robert C.W. Ettinger's Prospect

of Immortality, Trudy Weathersby's About:

Cryonics, or the European

Cryonics Page), or living to ensure the immortality of one's

memory.

Oblivion can also be avoided through the symbolic mode,

by remaining in the

memories of others through one's works, deeds, eponym (and no

institution appears to have produced more than

the medical establishment),

charities, and infamies. Of memory, Elie Wiesel wrote in All Rivers Run to the Sea:

Memoirs (N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995, p.150):

Memory is a passion no less powerful or pervasive than

love. What does it mean to remember? It is to live in more than one world,

to prevent the past from fading and to call upon the future to illuminate

it. It is to revive fragments of existence, to rescue lost beings, to cast

harsh light on faces and events, to drive back the sands that cover the

surface of things, to combat oblivion and to reject death.

Such immortality was evident in its Gershwin Centennial

Celebration in 1998, when the San Antonio Symphony performed "Rhapsody in Blue." What

made the performance special was that it was Gershwin who was playing the concert grand

piano. The instrument was a 1912 player piano, flown in from Denver, with a roll that had

preserved Gershwin's own keystrokes. As the music was about to begin a spotlight moved

across stage as if following the composer as he was taking his seat. An attendant even brought

a glass of wine and placed it above the keyboard for George to drink. Though "dead" since

1937, Gershwin was present. At the end of the concert, Wayne Marshall performed with

Gershwin. Sitting on one half of the bench--and ever careful not to be in the way--he

improvised on the upper scales as Gershwin played two more of his pieces.

Such immortality was evident in its Gershwin Centennial

Celebration in 1998, when the San Antonio Symphony performed "Rhapsody in Blue." What

made the performance special was that it was Gershwin who was playing the concert grand

piano. The instrument was a 1912 player piano, flown in from Denver, with a roll that had

preserved Gershwin's own keystrokes. As the music was about to begin a spotlight moved

across stage as if following the composer as he was taking his seat. An attendant even brought

a glass of wine and placed it above the keyboard for George to drink. Though "dead" since

1937, Gershwin was present. At the end of the concert, Wayne Marshall performed with

Gershwin. Sitting on one half of the bench--and ever careful not to be in the way--he

improvised on the upper scales as Gershwin played two more of his pieces.

Through memory the dead come to play many roles in

the affairs of the living. Observes Sandra Bertman:

The dead do not leave us: They are too powerful, too

influential, too meaningful to depart. They give us direction by institutionalizing

our history and culture; they clarify our relationship to country and cause.

They immortalize our sentiments and visions in poetry, music, and art.

The dead come to inform us of tasks yet to be completed, of struggles to

be continued, of purposes to be enjoined, of lessons they have learned.

We need the dead to release us from obligations, to open new potential,

to give us belongingness and strength to continue with our lives

(1979:151).

Such is the essence of symbolic immortality. It is

through memory that the living hold on to the dead, inspiring such creations

as the Great Pyramids of Egypt and the Taj

Mahal. Memories of the dead bring continuity and meaning to human existence,

which is why political regimes maintain national cemeteries for fallen

warriors, build monuments, and display embalmed remains (When a Moscow

visitor in the 1930s asked a Russian Communist, "Why did you embalm

Lenin?" he was told: "Because we don't believe in the immortality

of the soul" [Leszek Kolakowski, "The Mummy's Tomb." New

Republic, July 4, 1983:33]). New technologies are

now employed in this transcendence enterprise as William Sims Bainbridge details

in his "Web Based

Resources Relating to Technological Means for Achieving Immortality."

Of the artistic variant of this mode of

immortality, W.H. Auden observed in accepting his 1967 National Medal

for Literature:

Such is the essence of symbolic immortality. It is

through memory that the living hold on to the dead, inspiring such creations

as the Great Pyramids of Egypt and the Taj

Mahal. Memories of the dead bring continuity and meaning to human existence,

which is why political regimes maintain national cemeteries for fallen

warriors, build monuments, and display embalmed remains (When a Moscow

visitor in the 1930s asked a Russian Communist, "Why did you embalm

Lenin?" he was told: "Because we don't believe in the immortality

of the soul" [Leszek Kolakowski, "The Mummy's Tomb." New

Republic, July 4, 1983:33]). New technologies are

now employed in this transcendence enterprise as William Sims Bainbridge details

in his "Web Based

Resources Relating to Technological Means for Achieving Immortality."

Of the artistic variant of this mode of

immortality, W.H. Auden observed in accepting his 1967 National Medal

for Literature:

To believe in the value of art is to believe that it

is possible to make an object, be it an epic or a two-line epigram, which

will remain permanently on hand in the world. ... In the meantime, and

whatever is going to happen, we must try to live as E.M. Forster recommends

that we should: `The people I respect must behave as if they were immortal

and as if society were eternal. Both assumptions are false. But both must

be accepted as true if we are to go on working and eating and loving, and

are able to keep open a few breathing holes for the human spirit' (cited

in Laing, 1967:49).

But, as will be seen, such memories can also kindle

fears of the dead, whose spirits and ghosts can create mischief in the

world of the living unless properly placated ritually. See SpiritHistory:

Ephemera for glimpses of the nineteenth-century American spiritualism

movement.

The natural mode of symbolic immortality involves the

continuance of the natural world beyond the individual's lifetime. In a

sense, the ecology movement can be seen as an immortality attempt of many

individuals, whose efforts lead to the preservation of some natural habitat

or species of life. Interesting twists on this mode are provided by Eternal

Reefs, Inc., which turns cremated remains into living coral reefs, and Memorial

Ecosystems, which also reintegrates self remnants into the natural order.

CASE STUDY:

IMMORTALITY FOR THE ELECT IN SPORTS

During the twentieth century has arisen the great spectator

sports phenomenon. When archeologists dug up our culture and find a Dallas Cowboys helmet

and pom-poms, what inferences will be made about the late twentieth century American

culture? American cities float bonds to finance their community temples, the sports complex,

paid for by taxpayers whether fans or not. Indeed, sports rivals religion and politics as a shaper

and reinforcer of core cultural values.

There is, of course, much more to professional sports than

the mere game. With all their rules, regulations, and rigors of training, baseball, football, and

basketball have become high drama expressions of everyday life. As paintings abstract our

visual experience, and music abstracts the auditory, so the game abstracts the interdependency

of individuals occupying specialized roles within the economic sphere of life. There are within

the sociology of sport at least two perspectives which address this relation of sport to cultural

value systems. One, the sport a microcosm of American society thesis, directs attention to the

exaggeration of cultural values within the sports institution: competition, materialism, sexism,

the domination of the individual by bureaucracy, and the accentuation on youth (Eitzen and

Sage, 1978). The second perspective portrays sport as a secular, quasi-religious institution

which, through ritual and ceremony, serves to reinforce social values (Edwards, 1973, p. 90)

and to celebrate social solidarities. It is for these reasons that, like business, sports gets its own

section of newspapers.

Like religion, professional sports use past generations as

referents for the present and confer conditional immortality for their elect, through statistics and

halls of fame. Given the dramatic use of anabolic steroids in sports, even

at the risk of death, athletes are willing to die in exchange for symbolic

immortality. Chicago osteopath Bob Goldman (Death in a Locker Room, II)

asked Olympic-level athletes, "If you could take a magic pill that would make

you win every competition you were in for five years but at the end of that time

you would die, would you take it?"

In

1995, more than half said yes.

Although the

sampling was flawed, it nevertheless reveals that there are many willing to

exchange fame for death within this highly visible social arena of an

extremely competitive society.

- Hickok Sports.com's Index to Museums &

Halls of Fame

- International Association of Sports Museums and Halls of Fame

- Stickball Hall of Fame and

Museum

- Pro Football Hall of Fame and

Museum

- The College

Football Hall of Fame in South Bend

- International Boxing Hall of Fame and

Museum (Canastota, NY)

- Hockey Hall Of Fame

- International Swimming Hall of Fame and

Museum (Canastota, NY)

- International Bowling Hall of Fame and

Museum (Canastota, NY)

CASE STUDY:

IMMORTALITY FOR THE ROCK AND ROLL ELECT

While academicians

argued about our culture's death denials, the music of the post-war baby-boomers

was to become imbued with death, not only being a frequent theme of its songs,

but the premature fate of its performers (around whom dead rock star cults were

to emerge). One of the better known halls of fame enshrine their elect.

- We'll Always Remember--a Rock Obituary and Tribute Website

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum

IMMORTALITY

CAPITALISM-STYLE

Given its commodification of all aspects of life and

death--coupled with Americans' death fears, faith in science, and desires

for immortality--it is not surprising that capitalism has moved into the

businesses of life-extension and scientific resurrection. In 1996, British

researchers announced work on a "Soul

Catcher" memory chip which, within 30 years, will

be able to capture our feelings and thoughts. Said Chris Winter, head of

the Telecom artificial life team, "By combining this information with

a record of a person's genes, we could recreate a person physically, emotionally

and spiritually. This is the end of death--immortality in the truest sense"

(Reuters release cited in Parade Magazine, December 29, 1996). Can't

wait until 2030? Check out the Alcor Life

Extension Foundation, the self-proclaimed leader in cryonic

preservation, the feasibility studies brought to you from the American Cryonics Society, and a legitimating ideology from the Cryonics

Institute. See also "Scientific

and Medical Aspects of Human Cloning," a collection of

presentations from the August 2001 workshop sponsored by the National Academies'

Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy and the Board on Life

Sciences.

for immortality--it is not surprising that capitalism has moved into the

businesses of life-extension and scientific resurrection. In 1996, British

researchers announced work on a "Soul

Catcher" memory chip which, within 30 years, will

be able to capture our feelings and thoughts. Said Chris Winter, head of

the Telecom artificial life team, "By combining this information with

a record of a person's genes, we could recreate a person physically, emotionally

and spiritually. This is the end of death--immortality in the truest sense"

(Reuters release cited in Parade Magazine, December 29, 1996). Can't

wait until 2030? Check out the Alcor Life

Extension Foundation, the self-proclaimed leader in cryonic

preservation, the feasibility studies brought to you from the American Cryonics Society, and a legitimating ideology from the Cryonics

Institute. See also "Scientific

and Medical Aspects of Human Cloning," a collection of

presentations from the August 2001 workshop sponsored by the National Academies'

Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy and the Board on Life

Sciences.

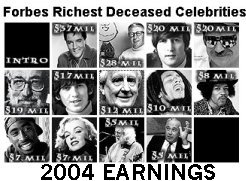

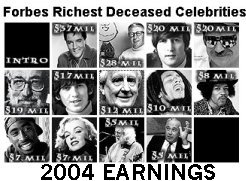

One guaranteed way for the dead to remain

"alive"

in capitalist economies is to continue to produce or consume. Following

this logic, Elvis (there

he is now!), Jim Morrison, and other "deceased" rock stars are

"alive" because they continue "producing" revenue from

their record sales. (If you want to put the dead to work peddling your product

odds are that you will have to deal with the Curtis

Management Group.) Mickey Mantle's afterlife seems assured given that

the value of his game artifacts inflated 25 to 100 percent in the year

following his death. Numerous communities have grown dependent on the

revenues generated by the dead, whose memories are collectively enshrined in the

myriad of halls of fame (such as the Paper

Industry International Hall of Fame in Appleton, Wisconsin, the

National Teachers Hall of Fame in Emporia,

Kansas, the American Police Hall of

Fame in Tutisville, Florida, or the

Insurance Hall of Fame on the

Campus of the University of Alabama). And the ten thousand Americans in irreversible vegetative

states remain "alive" because they are still consumers of medical

care.

One guaranteed way for the dead to remain

"alive"

in capitalist economies is to continue to produce or consume. Following

this logic, Elvis (there

he is now!), Jim Morrison, and other "deceased" rock stars are

"alive" because they continue "producing" revenue from

their record sales. (If you want to put the dead to work peddling your product

odds are that you will have to deal with the Curtis

Management Group.) Mickey Mantle's afterlife seems assured given that

the value of his game artifacts inflated 25 to 100 percent in the year

following his death. Numerous communities have grown dependent on the

revenues generated by the dead, whose memories are collectively enshrined in the

myriad of halls of fame (such as the Paper

Industry International Hall of Fame in Appleton, Wisconsin, the

National Teachers Hall of Fame in Emporia,

Kansas, the American Police Hall of

Fame in Tutisville, Florida, or the

Insurance Hall of Fame on the

Campus of the University of Alabama). And the ten thousand Americans in irreversible vegetative

states remain "alive" because they are still consumers of medical

care.

The property rights of the dead were extended by the 1998

Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. In 1790, copyrights lasted 14

years. The Bono act, upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2003,

lengthened protection by

20 years to 70 years after the death of the inventor or author, if the person is

known. (Works owned by corporations are protected for 95 years.)

The property rights of the dead were extended by the 1998

Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. In 1790, copyrights lasted 14

years. The Bono act, upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2003,

lengthened protection by

20 years to 70 years after the death of the inventor or author, if the person is

known. (Works owned by corporations are protected for 95 years.)

EMERGING TRANSCENDENCE INDUSTRIES

A new line of services are emerging where the deceased can

continue interacting with the living. In the early 1990s, for instance, a

Fairport, N.Y. company called Cards From Beyond appeared, offering one

the ability after death to send cards to loved ones for Easter, Christmas,

Thanksgiving, and anniversaries. From Loving Pup, Inc. came one of

the first posthumous

email services: "You care about your family, friends, and loved ones, show you

care by leaving them each an e-mail to be delivered after you pass on." As of

2007, other postmortem emailing opportunities exist through

The Last Email ("your thoughts live

on") and Deathswitch ("bridging

mortality"). Or how about placing a phone call from a deceased relative? With AT&T Labs' Natural

Voices speech software, voice cloning is now a reality. Type your

message and let the dead utter your words.

In addition to providing resources on estate planning, funeral planning, end-of-life care, grief

and loss, FinalThoughts.com and

MyLastEmail.com also offer "Afterlife Email Service."

And there's also AFTERLIFE, “a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to archive Web sites after their authors die and can no longer support them.”

This mission is shared with Immortality Foundation, "a non-profit corporation whose sole purpose

is to be the permanent guardians of the collections of words and other materials

entrusted to us, thus allowing these materials to remain alive as long as humanly

possible."

In addition to providing resources on estate planning, funeral planning, end-of-life care, grief

and loss, FinalThoughts.com and

MyLastEmail.com also offer "Afterlife Email Service."

And there's also AFTERLIFE, “a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to archive Web sites after their authors die and can no longer support them.”

This mission is shared with Immortality Foundation, "a non-profit corporation whose sole purpose

is to be the permanent guardians of the collections of words and other materials

entrusted to us, thus allowing these materials to remain alive as long as humanly

possible."

Relict Memorials of

Mill Valley, California, will turn loved ones' cremated remains into

customized granitelike slabs or sculptures. Cremains are mixed with pulp

by Timothy Hawley Books

to produce the pages of bound volumes called "bibliocadavers."

SeaRest Inc. will encase cremains within concrete blocks to create artificial

reefs off the Florida coast as a "living memorial." Space

Services Inc., formerly Celestis, "makes it possible to honor the dream and

memory of your departed loved one by launching a symbolic portion of cremated

remains in Earth's orbit, on the Lunar surface or deep space." Cremains are also

turned into diamonds by LifeGem and into pencils by

Carbon

Copies. By 2007, a Funerary Art Movement was recognized (see

Funeria for examples) and the first

gallery of cremation urns and memorial art opened in northern California.

(Click

here for other cremains-dealing industries.)

Relict Memorials of

Mill Valley, California, will turn loved ones' cremated remains into

customized granitelike slabs or sculptures. Cremains are mixed with pulp

by Timothy Hawley Books

to produce the pages of bound volumes called "bibliocadavers."

SeaRest Inc. will encase cremains within concrete blocks to create artificial

reefs off the Florida coast as a "living memorial." Space

Services Inc., formerly Celestis, "makes it possible to honor the dream and

memory of your departed loved one by launching a symbolic portion of cremated

remains in Earth's orbit, on the Lunar surface or deep space." Cremains are also

turned into diamonds by LifeGem and into pencils by

Carbon

Copies. By 2007, a Funerary Art Movement was recognized (see

Funeria for examples) and the first

gallery of cremation urns and memorial art opened in northern California.

(Click

here for other cremains-dealing industries.)

From Germany comes a curious form of bodily immortalization

called plastination.

Using a process invented by Dr. Gunther von Hagens, real corpses are

transformed into plastic. A revolutionary teaching tool for anatomy

classes, von Hagens' creations now tour the world as commercial

exhibitions of "anatomical artwork," attracting crowds and ethical

criticisms. Listen to NPR's April 30, 2001 report on "Body Art" here.

From Germany comes a curious form of bodily immortalization

called plastination.

Using a process invented by Dr. Gunther von Hagens, real corpses are

transformed into plastic. A revolutionary teaching tool for anatomy

classes, von Hagens' creations now tour the world as commercial

exhibitions of "anatomical artwork," attracting crowds and ethical

criticisms. Listen to NPR's April 30, 2001 report on "Body Art" here.

Electronically connect with the dead with Memory Medallion, a steel-encased computer chip that can be

embedded in tombstones and memorial

plaques. Activated by a "touch wand," visitors can download a five-minute minimovie into their laptops

or PDAs.

embedded in tombstones and memorial

plaques. Activated by a "touch wand," visitors can download a five-minute minimovie into their laptops

or PDAs.

Finally, comes a product foreshadowing things to come from the biotech industries:

a Limited Edition Abraham Lincoln Pen containing replications of the 16th President's

DNA, produced by StarGene

Inc.. Founded by Kary Mullis, 1993 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry,

the company uses his patented PCR (polymerase chain creation) technology, to

clone DNA. This certainly is a new twist on the hair flowers Victorians

made to help preserve the memories of deceased family members.

CEMETERIES

Beware ye who pass by As ye be now so once was I As I be now so must

ye be Prepare for death and follow me.

Beware ye who pass by As ye be now so once was I As I be now so must

ye be Prepare for death and follow me.

--Common 18th-Century New England Epitaph

Another way of avoiding oblivion is at least having

one's existence acknowledged on one's tombstone epitaph.

(See "The

inevitable hour," a collection of 17th- and 18th-century epitaphs from The

Economist.)

Cemeteries--the word from the Greek for "sleeping

place"--are cultural institutions that symbolically dramatize many

of the community's basic beliefs and values about what kind of society

it is, who its members are, and what they aspire to be. We are, for instance, stratified in death

as we are in life, evident in the segregations of community cemeteries (or within a community's

cemetery) by race, ethnicity, religion, and social class. (Our class, in fact, has even located a

"Republican Cemetery" in the Texas Hill Country.) In 1999, as a fence separating blacks and

whites was being removed from a Jasper, Texas cemetery (where, a year earlier, three young

white men dragged to death behind their pickup truck James Byrd Jr., a disabled 49-year-old

black man) another was being erected in Tynan, Texas, separating the German-American

section of the Waldheim Cemetery from the Hispanic-American

section.

it is, who its members are, and what they aspire to be. We are, for instance, stratified in death

as we are in life, evident in the segregations of community cemeteries (or within a community's

cemetery) by race, ethnicity, religion, and social class. (Our class, in fact, has even located a

"Republican Cemetery" in the Texas Hill Country.) In 1999, as a fence separating blacks and

whites was being removed from a Jasper, Texas cemetery (where, a year earlier, three young

white men dragged to death behind their pickup truck James Byrd Jr., a disabled 49-year-old

black man) another was being erected in Tynan, Texas, separating the German-American

section of the Waldheim Cemetery from the Hispanic-American

section.

These cities of the dead may have been the precursors of the

cities of the living. Lewis Mumford speculated in The City in History: Its Origins, Its

Transformations, and Its Prospects

Early man's respect for the dead ... perhaps had an

even greater role than more practical needs in causing him to seek a fixed

meeting place and eventually a continuous settlement. Though food- gathering

and hunting do not encourage the permanent occupation of a single site,

the dead at least claim that privilege. Long ago the Jews claimed as their

patrimony the land where the graves of their forefathers were situated;

and that well-attested claim seems a primordial one. The city of the dead

antedates the city of the living. In one sense, indeed, the city of the

dead is the forerunner of the city of the living (1961:7).

As members of the Association

for Gravestone Studies Home Page are quick to remind us, most of what

we know of the past is based on grave contents and inferred from funerary

artifacts. For example, anthropological excavations of graveyards have

revealed that the average height of Icelanders decreased steadily from

A.D. 1200 to 1800, coinciding with climactic deterioration; that, based

on the bones of 87 women buried in a British crypt between 1729 to 1852,

modern women's bones are weaker than those of their ancestors.

As members of the Association

for Gravestone Studies Home Page are quick to remind us, most of what

we know of the past is based on grave contents and inferred from funerary

artifacts. For example, anthropological excavations of graveyards have

revealed that the average height of Icelanders decreased steadily from

A.D. 1200 to 1800, coinciding with climactic deterioration; that, based

on the bones of 87 women buried in a British crypt between 1729 to 1852,

modern women's bones are weaker than those of their ancestors.

No content analysis of a cemetery would be complete without

consideration of the tombstones and their inscriptions. The relative

sizes of the stones have been taken as indicators of the relative power

of males over females, adults over children, and rich over poor. In immigrant

graveyards, the appearance of inscriptions in English signifies the pace

of males over females, adults over children, and rich over poor. In immigrant

graveyards, the appearance of inscriptions in English signifies the pace

of a nationality's enculturation into American society. The messages

and

art reflect such things as the emotional bonds between family members and

the degree of religious immanence in everyday life (for insight into the meaning of tombstone

iconography see Cristina Leimer's The

Tombstone Traveller's Guide, Betty

Willsher's Emblems of Mortality, and Steve Johnson's [webmaster of Cemetery

Records Online] The Cemetery Column).

For one of the best resources on early American gravestones, see the Farber

Gravestone Collection, courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society. What inferences can you make from the following chronology of images? Be careful. Consider

the lessons learned in the analysis of early nineteenth-century gravestones of Geauga county, Ohio.

of a nationality's enculturation into American society. The messages

and

art reflect such things as the emotional bonds between family members and

the degree of religious immanence in everyday life (for insight into the meaning of tombstone

iconography see Cristina Leimer's The

Tombstone Traveller's Guide, Betty

Willsher's Emblems of Mortality, and Steve Johnson's [webmaster of Cemetery

Records Online] The Cemetery Column).

For one of the best resources on early American gravestones, see the Farber

Gravestone Collection, courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society. What inferences can you make from the following chronology of images? Be careful. Consider

the lessons learned in the analysis of early nineteenth-century gravestones of Geauga county, Ohio.

Here's one reading: The imminent millennialism sensed

by the Puritans and their contempt for mortal existence led to the skull

and crossbones being the most persistent tombstone symbol of early New

England days (Habenstein and Lamers, The History of Funeral Directing

1962:201). Over time, with increasing hope in a desirable immortality and

the Romantic faith in the man's perfectibility, there was a concurrent

change from skeletal images to portrayals of winged cherubs on the

gravestones.

With increasing religious pluralism, urbanization,

literacy, and the growing role of science and technology, Christianity

retreated from everyday life. With this fading of the sacred, moral absolutes

were to dissolve, and no longer could identity taken for granted. During

the nineteenth century, the private self and the cult of romantic death

arose out of the emotional attachments that were replacing the traditional

economic bondings of family members. People became more concerned with

others' deaths than with their own, realizing that it was only through

these significant others that one's true, unique self was made possible.

As grief became the pre-eminent emotion, tombstone art shifted to willow

trees, ornate urns, and grieving widows or angels. For a tour of Mt.

Auburn Cemetery, the site that epitomized the rural cemetery movement of

the first half of the nineteenth century, click

here.

these significant others that one's true, unique self was made possible.

As grief became the pre-eminent emotion, tombstone art shifted to willow

trees, ornate urns, and grieving widows or angels. For a tour of Mt.

Auburn Cemetery, the site that epitomized the rural cemetery movement of

the first half of the nineteenth century, click

here.

The contemporary uniformity of tombstones bearing brief

bureaucratic summaries of the identities of those beneath can be taken

as evidence of the rationalization, bureaucratization, and homogenization

of our times. But there are some clear signs of change. Check out

the product on the left, a digital tombstone.

If you enjoy such analyses you may be a taphophile and not even know it!

For books and links on the subject check out

"Books of

Bones." Other resources:

If you enjoy such analyses you may be a taphophile and not even know it!

For books and links on the subject check out

"Books of

Bones." Other resources:

- City

of the Silent, "the web's most extensive cemetery site"

- Cyndi's List of

Cemeteries and Funeral Homes, this site of genealogy fame has an

impressive listing of cemeteries

- Cemeteries: Optima

philosophia et sapientia est meditatio mortis another great index of cemetery sites

- Jonathan Clark's After Life: Streatham Cemetery--animated photographs through four seasons

- Northstar Gallery of Cemetery and Memorial Art--featuring some of the most sensual

funerary images from Europe and the U.S.

- Cities

of the Dead--a guide to the cemeteries of New Orleans

- The Sepulcher

- The

Page of the Dead-- European cemeteries and stories of the fates of some

dead notables

- Underground Paris--"Far below the city streets of Paris, in the quiet, damp darkness,

seven million Parisians lie motionless. Their skeletons, long since disinterred

from the churchyard graves their survivors left them in, are neatly stacked and

aligned to form the walls of nearly one kilometer of walking passage."

- Writ

in Water: An International Gallery of Memorials for the

Dead--images from England, France, Italy, Ireland, Salem and Concord Massachusetts, New Orleans, and Santa Cruz

- The Adams Residence photos of English, Irish and Parisian cemeteries in

addition to macabre short stories and famous last words

- OldBones.Net superb photographs of old New England tombstones

& mortuary relics, also featuring collection of humorous epitaphs. A

related photo-rich site is "Old

Burial Hill, Marblehead," MA.

- Steve Grimm's Old West Gravesites

- Beneath Los Angeles Memorials of "the famous, the infamous, and the just plain dead"

- OldBones.Net superb photographs of old New England tombstones

& mortuary relics, also featuring collection of humorous epitaphs

- 17th, 18th and 19th Century Cape Cod Gravestones

- The Political Graveyard--"The Web Site That Tells Where the Dead Politicians are

Buried," broken down by a huge alphabetized index of American cemeteries

- Graveyards of

Chicago

- And

don't forget the critter memorials! Roadside Pet Cemetery

- Professor Gary Collison's

Pennsylvania's Historic Cemeteries: A Brief History

- Steve Paul Johnson's "The

Cemetery Column"

- Tomb With a View--a quarterly newsletter "about the appreciation, study and preservation of the art and heritage in

historic cemeteries"

- Necronicles--a webzine for cemetery photographers

- Sandra Kehoe-Forutan's Necrogeography Bibliography

- CemSearch a tool to search for surnames through cemetery inscriptions pages throughout the web

- The

Home Page of Summum: Is mummification for you or your pet?

A new strategy for body disposals is to send cremains into

earth orbit, and even into deep space. Four missions have been launched as

of Spring 2001 (check site for launch photos and videos). For $5,300 Celestis will orbit your ashes in its low-end

"Earthview Service." Dr. Eugene Shoemaker (of comet fame) was a

passenger on the first "Lunar Service," which will set you back

$12,500 (payment plans available). Yet to come is the "Voyager

Service," which will send cremains into deep space.

ELECTRONIC

MEMORIALS

One product of Romanticism and the rural cemetery

movement

of the early nineteenth cemetery was the Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge,

Massachusetts. This garden cemetery apparently captured the imaginations

of the time as it became a major tourist destination for both American

and European visitors, and was to be frequently modeled. It is a didactic

place where the stories of unique selves are revealed on the tombstone

inscriptions. How different these biographical markers are from the contemporary

homogenized inscriptions, where little more than bureaucratic details (e.g.,

name with birth and death dates) are noted.

In reaction to such homogenized levelings, it is not

surprising that individuals now seek alternative ways to provide dignity

and identity to their deceased loved ones, to reaffirm that their lives

have made a difference. For a formal sociological analysis of this trend see Hans Geser's "Yours Virtually Forever:

Death Memorials and Remembrance Sites in the WWW". Examples of such electronic

memorial sites include:

OTHER WAYS TO

REMEMBER/ACKNOWLEDGE THE

DEAD

OBITUARIES

One facet of funerary ritual involves the obituary.

And for whom are they written and for what reason? Indeed, obituaries are

written so that the broader community knows of the loss of one of its members

and of the bereavement status of the principle survivors. But they also

have a didactic function. Like the eulogy, it is here where a biography

is summed up, an individual's contributions to the social order are recalled,

and the meaning of a life is assessed. When you think about it, there are

no other times when such grand summations are made and reflected

upon.

One facet of funerary ritual involves the obituary.

And for whom are they written and for what reason? Indeed, obituaries are

written so that the broader community knows of the loss of one of its members

and of the bereavement status of the principle survivors. But they also

have a didactic function. Like the eulogy, it is here where a biography

is summed up, an individual's contributions to the social order are recalled,

and the meaning of a life is assessed. When you think about it, there are

no other times when such grand summations are made and reflected

upon.

Obituaries, these "social registers of the middle

class" as George Gerbner called them, provide a wealth of information

for social scientists. Want to observe changes in the sexism or racism

in your community? Why not look at a sample of a century's worth of obituaries

in your local newspaper and record the percentage of the obituaries going

to women and minorities and note their length relative to obituaries given

to white males (controlling for age at death and cause)? For an illustration,

see "Death as a Measure of Life: A Research Note on the Kastenbaum-Spilka

Strategy of Obituary Analyses" in Omega: Journal of Death and Dying,

17(1), 1986-87:65-78. In his obituary analyses, Gary Long ("Organizations

and Identity: Obituaries 1856-1972," Social Forces 1987, 65(4):964-1001)

reported a longitudinal trend toward impersonal, standardized, categorical,

"objective" portrayals of completed lives. Rarely do we learn

nowadays from these resume-type bios how others' lives were impacted by this person. To what extent is such silence related to the moral crises

of our times?

- Tributes.com--"Because Every Life Has a Story"

- Yahoo's

Obituaries

- National Obituary Archive

- Obituary Links Page--State-by-state directory of obituaries

& obituary resources

- Obituary Central--"Headquarters for researching obits on the web"

- New York TimesObituaries--both contemporary and "from the archives"

- Good Bye! The Journal of Contemporary Obituaries

- The Blog of Death

- Annie

Wiley and her Obituary Scrapbook (Kentucky obits from 1924-64)

- Celebrity Obituaries

Fear of Flying Site: Celebrities who died in airplane crashes

The Bond Orchard: Deceased B-movie actors and directors

Fuller Up: The Dead Musician Directory (and how they got that way)

ROADSIDE MEMORIALS

Across the country we see the proliferation of roadside crosses, or

descansos, marking traffic fatalities. Though many point to Hispanic origins of the practice, other West European groups

make similar memorializations. They indicate not only the time of death, which

we've long dutifully noted on gravestones, but also the precise place of

individuals' untimely deaths.

From ChrisTina Leimer's Tombstone Traveller's Guide,

Roadside Memorials: Marking Journeys Never Completed

Roadside Memorials: A Photographic Documentary

Another commodification of grief: Roadside Memorials--mail-order roadside crosses.

"Roadsidememorials.com will not be responsible for any accidents or injuries

due to the placement of your cross."

HALLS OF

FAME

In February of 1985 six pioneer inventors were inducted

into the The National Inventors

Hall of Fame in Arlington, Virginia. These inventors, credited with

originating air-conditioning, the artificial heart, phototypesetting, tape

recording and Teflon, join 53 others. One year later, seven recently discovered

asteroids were named for the seven astronauts who died in the explosion

of the space shuttle Challenger. In 1991, Barry Goldwater, Chuck Connors

("The Rifleman") and James Drury ("The Virginian")

were inducted into the Cowboy

Hall of Fame Home in Oklahoma City. In 1994, the Comedy Hall of Fame

inducted Bob Hope and George Carlin.

Work, like religion, provides immortality to the elect.

Art galleries and libraries are filled with works of the dead. Gutzon Borglum

is immortalized by his Mt. Rushmore Memorial, Leonardo da Vinci by the

"Mona Lisa", Thomas Edison by the incandescent bulb, and Henry

Ford by the automobile bearing his name. The Hartford, Connecticut law

firm of Day, Berry & Howard sports the name of three deceased partners,

and the memories of scientists live on in the names of the astronomical

bodies, plants and animals they either discovered or hybridized. Work provides

individuals the major opportunity to "leave one's mark."

As is evident in the links below, corresponding with

the rapid differentiation of the workplace has been a proliferation of

heavens. Memories of the work elite are maintained in a host of halls of

fame, for pickle packers and auctioneers alike. If one fails to gain the

highest forms of work-related immortality, as through induction into a

hall of fame or through one's works, there still possible means for being

remembered. In particular, there are the numerous "Who's Who"

compilations (i.e., Who's Who Among Elementary School Principles,

Who's Who In Commerce and Industry, Who's Who In Rock, and

Who's Who In Science in Europe). And, for academicians, if one fails

to make this compilation, one can at least make the card catalogue. Even

better, one's ideas can be celebrated in school texts--one's name is at

least remembered and perhaps even quizzed upon.

- National Inventors Hall of Fame

- International Photography Hall of Fame

- Labor Hall of Fame

- American Police Hall of Fame

- Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame

- U.S. Army Warrant Officer Hall of Fame (Ft. Rucker, Alabama)

- U.S. Army Military Police Hall of Fame (Ft.

Leonard Wood, MO)

- Kansas National Guard Hall of Fame

- National Women's Hall of Fame

- International Aerospace Hall of Fame

- National Aviation Hall of Fame

- Accounting Hall of Fame

- National Mining Hall of Fame

- Poker Dealer Hall of Fame

- Rockabilly Hall of Fame

TRANSCENDING

DEATH

THROUGH ORGAN

DONATIONS

- UCI

Willed Body Program: organ donation & mortuary science

- Body

Donation

- Body

Donations--Cadavers--Mortuary Science

- TransWeb

- Transplantation and Donation

THE POWER OF THE

DEAD OVER THE LIVING:

LAST

WILLS

AND TESTAMENTS

...a sociology of death not based on a sociology of

types of inheritance risks being overly idealist and abstract.

--Jean-Claude Chamboredon

To what extent can the dead continue to exercise control

over the living through stipulations in trusts and wills? Money is most

certainly an instrument for perpetuating not only the family name (and

whatever that might entail) but the memory of the deceased as well. An

estate, a "patrimony," represents an image of the father, and

in patriarchal societies not even socialist regimes are willing to destroy

this immortal visage through massive estate taxes in order to redistribute

the wealth of the living. Need a research topic? How about

"incentive trusts"?

To what extent can the dead continue to exercise control

over the living through stipulations in trusts and wills? Money is most

certainly an instrument for perpetuating not only the family name (and

whatever that might entail) but the memory of the deceased as well. An

estate, a "patrimony," represents an image of the father, and

in patriarchal societies not even socialist regimes are willing to destroy

this immortal visage through massive estate taxes in order to redistribute

the wealth of the living. Need a research topic? How about

"incentive trusts"?

- Wills of Celebrities and Ordinary People, 1493-1998

- Mark

Welch's Wills and Testaments of the famous and not so famous on the web

- Leave A Legacy

NDEs: EVIDENCE OF A HEREAFTER?

Since Raymond Moody's Life After

Life (1975), we have heard much about Near-Death Experiences (or

NDEs): the out-of-body experiences, a life-review, the tunnel of darkness,

receptions with deceased loved ones, people of light, the sense of peace

and painlessness, and the reluctance to return. A 1981 Gallup poll found

some 15 percent of the surveyed reporting having had such experiences.

Such reports became the cover story ("Visions of Life After Death:

The Ultimate Mystery") of the March 1992 issue of Life magazine and

the subject of Betty Eadies's best-seller Embraced by the Light.

There is a Journal of Near-Death Studies, an International

Association for Near-Death Studies, and over one hundred support groups.

In January 2002, ABC News ran the story "Brushes

With Death: Scientists Validate Near-Death Experiences."

Since Raymond Moody's Life After

Life (1975), we have heard much about Near-Death Experiences (or

NDEs): the out-of-body experiences, a life-review, the tunnel of darkness,

receptions with deceased loved ones, people of light, the sense of peace

and painlessness, and the reluctance to return. A 1981 Gallup poll found

some 15 percent of the surveyed reporting having had such experiences.

Such reports became the cover story ("Visions of Life After Death:

The Ultimate Mystery") of the March 1992 issue of Life magazine and

the subject of Betty Eadies's best-seller Embraced by the Light.

There is a Journal of Near-Death Studies, an International

Association for Near-Death Studies, and over one hundred support groups.

In January 2002, ABC News ran the story "Brushes

With Death: Scientists Validate Near-Death Experiences."

What is to be made of such reports? Does their supposed

universality suggest evidence of the existence of an afterlife or can they

be explained (which, interestingly, comes from the Latin word "to

flatten out") in terms the physical effects of brain activity, such

as cerebral anoxia due to oxygen deprivation or the stimulation of some

massive release of endorphins (perhaps Mother Nature's compensation for

extinguishing the survival impulse)? Whatever they mean, they certainly

call both faith and science into question. It is interesting how many religious

figures accept the scientific explanation (it would be upsetting if the

quality of NDEs was unrelated to the moral worthiness of the lives lived

by their experiencers) while some scientists, like physician Michael Sabom

(Recollections of Death: A Medical Investigation), are accepting

the religious perspectives.

Several observations. First, such experiences are associated

not with death but with the dying process. Second, increases in their reported

frequencies may well be attributable to the evolution of our medical arts,

which (as evidenced by the thousands of those in persistent vegetative

states) have created a new purgatory, a new liminal realm between the worlds

of the living and the dead. Third, there is an absence of language to describe

their out-of-the-ordinary nature. Unlike the Tibetans, Americans do not

have over one hundred words to describe different states of being; they

do not have (at least before Moody and NDE tags) cultural "frames"

for their decipherment. Fourth, we must not forget the highly religious

nature of Americans (see "You

Never Have to Die". And finally, such experiences may be one of

those Jungian archetypes owing to their apparent universality. When observing

parallel descriptions in religious and philosophical (recheck Plato's

story of Er in the Republic) texts, Moody argues how NDEs may

be the origin of such notions as the soul, the spirit, and human duality.

Several observations. First, such experiences are associated

not with death but with the dying process. Second, increases in their reported

frequencies may well be attributable to the evolution of our medical arts,

which (as evidenced by the thousands of those in persistent vegetative

states) have created a new purgatory, a new liminal realm between the worlds

of the living and the dead. Third, there is an absence of language to describe

their out-of-the-ordinary nature. Unlike the Tibetans, Americans do not

have over one hundred words to describe different states of being; they

do not have (at least before Moody and NDE tags) cultural "frames"

for their decipherment. Fourth, we must not forget the highly religious

nature of Americans (see "You

Never Have to Die". And finally, such experiences may be one of

those Jungian archetypes owing to their apparent universality. When observing

parallel descriptions in religious and philosophical (recheck Plato's

story of Er in the Republic) texts, Moody argues how NDEs may

be the origin of such notions as the soul, the spirit, and human duality.

It goes without saying that the research possibilities

into Near-Death Experiences are numerous. Instead of exploring the veracity

or universality of such experiences, we could focus on the understudied

consequences of having had them. How are lives changed? For some, a NDE

has led to new life missions. For one San Antonian, the experience was

a catalyst for personal growth, and he now explores the ways in which NDEs

can be painlessly duplicated for collective growth. For another, the experience

instructed her to "do something" for children in exchange for

her life. She created SAV- BABY (1-800-SAV-BABY; 301 S. Frio, Suite 480

San Antonio, TX 78207), a non-profit organization, now approaching

its ninth year, dedicated

to saving abandoned newborn babies.

Given how NDEs may enrich the meaningfulness of existence

and instill an altruistic direction to life, it should not be surprising that some

researchers are attempting to artificially create the experience. Dr.

Karl Jansen responded to this page with reference to one substance that produces

such experiences and to his new book Ketamine:

Dreams and Realities.

- Kevin Williams' Near-Death Experiences and the Afterlife

- International

Association for Near-Death Studies

- Near-Death Experience Research Foundation

- From About.com, Guide Picks for Near-Death Experiences

- Kevin Williams' Near-Death Experiences and the Afterlife

- Scott

Roberts's Collection of personal accounts, researcher interviews on NDEs

- Home Page of the After-Death Communications

Project

- Diane Goble's "Beyond the Veil--Q&A from

a NDE experiencer

-

Yahoo! Directory of Near-Death Experiences

- The Dannion Brinkley story and how NDEs supposedly produced visions of the future

- Keith Augustine's

"The Case Against Immortality"

GHOSTS: MORE

EVIDENCE OF A

SPIRITUAL

REALM?

In Man, God, and Immortality: Thoughts on Human

Progress (Cambridge: Trinity College Press, 1968), Sir James George

Frazer argues that the belief in the existence of ghosts is one manifestation

of human's belief in the immortality of the human soul, leading to "race

after race, generation after generation, to sacrifice the real wants of

the living to the imaginary wants of the dead" (p. 380). Any thoughts

why Virginia, according to the Ghost Research Society, ranks first in ghost

population? (You may want to check out the National

Directory of Haunted Places for the spirit hangout closest to you.)

Need a spiritual entity to commune with? In the early 1980s, clients of

California's Ghost Adoption Agency could for $185 "adopt" such

personages as William Shakespeare or Attila the Hun.

- SpiritWeb: A "Comprehensive Web-Site Promoting Alternative Spiritual Consciousness"

- About.com's Guide picks for Ghosts and Hauntings

- Prairie

Ghosts.

Ghost detecting equipment available here, along with the ghost photograph

of the week.

- Ghost

Hunters Gallery. Ghost photography is alive and well!

- Paranormal sites--with

your

mind in mind!

Return to Kearl's Death Index

Return to Kearl's Death Index

Arthur Koestler, noted author and founder of Exit,

wrote before his own suicide: "If the word death were absent from

our vocabulary, our great works of literature would have remained unwritten,

pyramids and cathedrals would not exist, nor works of religious art-and

all art is of religious or magic origin. The pathology and creativity of

the human mind are two sides of the same medal, coined by the same mintmaster"

(1977).

Arthur Koestler, noted author and founder of Exit,

wrote before his own suicide: "If the word death were absent from

our vocabulary, our great works of literature would have remained unwritten,

pyramids and cathedrals would not exist, nor works of religious art-and

all art is of religious or magic origin. The pathology and creativity of

the human mind are two sides of the same medal, coined by the same mintmaster"

(1977).

Such is the essence of symbolic immortality. It is

through memory that the living hold on to the dead, inspiring such creations

as the Great Pyramids of Egypt and the

Such is the essence of symbolic immortality. It is

through memory that the living hold on to the dead, inspiring such creations

as the Great Pyramids of Egypt and the

Beware ye who pass by As ye be now so once was I As I be now so must

ye be Prepare for death and follow me.

Beware ye who pass by As ye be now so once was I As I be now so must

ye be Prepare for death and follow me.

Since

Since