FUNERARY RITUAL

& THE FUNERAL INDUSTRY

Funerals are the greatest source of social change

Funerals are the greatest source of social change

--Kenneth Boulding

Lest we forget, funerals really are the social event.

Consider the February 1990 funeral of publisher Malcolm Forbes. The mourners

included ex-President Richard Nixon, actress Elizabeth Taylor (who sat

in front pew with the ex-President), Chrysler Chairman Lee Iacocca, Hell's

Angels cyclists, Barbara Walters, Joan Rivers, David Rockefeller, Ann Landers,

Mrs. Douglas MacArthur, former New York City mayor Edward Koch, and 1,700

others. What other social occasion can bring together such a collection

of individuals?

HOW, SOCIOLOGICALLY, WOULD YOU EXPLAIN THIS CUSTOM?

Up until the early 18th century, both American Northerners and Southerners observed the English custom of

the deceased's family providing each of their funeral guests with a black scarf, a mourning ring, and a pair of black

gloves--or at least as many of these that they could afford. In 1721, laws

were passed limiting such gifting to the six pallbearers and the officiating

minister.

(Mary Cable. 1969. American Manners

& Morals: A Picture History of How We Behaved and Misbehaved. NY:

American Heritage Pub. Co.)

|

Rituals are condensed forms of experiences, tips of icebergs of meanings and social mechanisms for transformations.

These enactments of cultural belief systems go beyond mere ceremony, as Victor Turner noted when defining

ritual as "prescribed formal

behavior for occasions not given over to technological routine, having

reference to beliefs in invisible beings or powers" (From Ritual to

Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, p. 29) that preserve the structures

of both self and society. In rite-of-passage rituals, of which funerals are a type, old

used-up selves are shed so new ones can be instilled. With

increasing individualism and profoundly different times, traditional rituals may

no longer "work" and thus we see the rise of do-it-yourself

funerals.

Rituals are condensed forms of experiences, tips of icebergs of meanings and social mechanisms for transformations.

These enactments of cultural belief systems go beyond mere ceremony, as Victor Turner noted when defining

ritual as "prescribed formal

behavior for occasions not given over to technological routine, having

reference to beliefs in invisible beings or powers" (From Ritual to

Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, p. 29) that preserve the structures

of both self and society. In rite-of-passage rituals, of which funerals are a type, old

used-up selves are shed so new ones can be instilled. With

increasing individualism and profoundly different times, traditional rituals may

no longer "work" and thus we see the rise of do-it-yourself

funerals.

Resources on funerals & their social functions

Resources on funerals & their social functions

- Betram S. Puckle's 1926

Funeral Customs: Their Origin and Development

- Museum of Funeral Customs, from the Illinois Funeral Directors Association

- Dan Meinwald's

funeral page, historical overview of the ritual

- Funeral Customs, from the

New River Group's historical resources site

- Stephen Buckley's "In Africa, Funerals Use Rituals of Joy to

Ease Sorrow," Washington Post

THE FUNERAL INDUSTRY

As previously developed, death in developed societies has become hidden

from everyday life. In the United States and other developed countries,

death and the dying process are largely institutionalized, and bereaved

families pay strangers to transport, sanitize, reconstruct, clothe and

dispose of their dead members. These are employees of the estimated $15 billion a

year (as of 2001), increasingly

consolidating American death care industry. The major players (in

order): Service

Corporation International, Alderwood

Groups, Stewart Enterprises,

StoneMor, and Carriage

Services.

As of 2000, there are more funeral homes (23,000, serving the 2.32 million deaths each year) than nursing homes

(17,000, serving 1.6 million residents) in the

United States. That means that each of these

curiously-labeled "homes" attends to roughly the same number of

"cases": 94 residents on average per nursing home and 101 post-nursing

home residents per funeral home. Funeral industry stocks have consistently

produced some of the highest returns of any industry over the past few decades.

Concurrently , this

industry has received considerable

criticism, most notably in Jessica

Mitford's 1963 classic, The American Way of Death . (See

also U.S. News & World Report's March 23, 1998 cover story "The Deathcare Business: The Goliaths of the funeral

industry are making lots of money off your grief",

Suzi Parker's January 12, 2001 Salon article "Get

Your Laws Off My Coffin!", and perhaps listen to NPR's

"The Funeral Industry" with Karen Leonard, Mitford's research

assistant.) Allegations that

its practitioners have taken unwarranted advantage of those in the throes

of grief have led to Congressional hearings, new trade practices rules

from the Federal Trade Commission, and undercover sting operations staged

by various consumer groups. Industry regulation varies considerably, as

noted in the GAO's August 2003 report, "Death

Care Industry: Regulation Varies across States and by Industry Segment."

Cemeteries have entered into the funeral service

competition and, unlike funeral homes, are not covered by the 1984 Federal

Trade Commission Rules

requiring itemized price lists.

However, there is evidence that new understandings

are emerging between the industry and a more informed public. For instance,

check out the Funeral

Ethics Association, whose purpose, according to its Constitution, is

"to provide the public and the profession with a balanced forum for

resolving misunderstandings and to elevate the importance of ethical practices

in all matters related to funeral service."

Class dynamics produce an interesting twist in our

tale of cultural death-denials. Funeral directing is of few state-recognized

professions that provides upward mobility for those who, by chance of birth,

are often thwarted in their attempts to achieve professional respect. This

status has been hard won, deriving from over a century of attempts in the

United States to expand and to legitimate its occupational purview, to

establish its craft as a "science".

Cross-culturally, it is often the lower classes that were typically assigned

to handling the dead, such as the Eta of Japan or the Untouchable in India.

But the so-called "Dismal Trade" of eighteenth century England

was to evolve into a host of thanatological specialists seeking social

recognition and status: embalmers, restorers, morticians, and some even

calling themselves "grief experts".

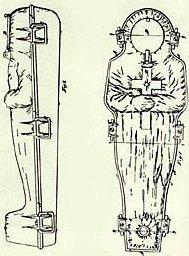

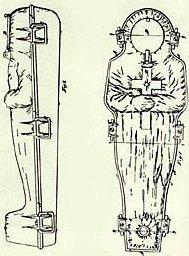

To give the industry and its product historical

legitimation,

the National Funeral Directors Association

commissioned Robert Habenstein and William Lamers (1955). Their book, The History

of American Funeral Directing, reviews the history of funeral practice in Western

civilization from ancient Egypt on, and was required reading for years in mortuary colleges.

(Tour the National Museum of Funeral History

in Houston.) The Web of

Time has two articles on the industry's history and its products: Julian W. S. Litten's

"Going in

Style-The Coffin: Its Place in Social History," and Richard Akerman's

"Picture Perfect: A

Cast-Iron Case." See also John L. Konefes and Michael K. McGee's "Old

Cemeteries, Arsenic, and Health Safety."

To give the industry and its product historical

legitimation,

the National Funeral Directors Association

commissioned Robert Habenstein and William Lamers (1955). Their book, The History

of American Funeral Directing, reviews the history of funeral practice in Western

civilization from ancient Egypt on, and was required reading for years in mortuary colleges.

(Tour the National Museum of Funeral History

in Houston.) The Web of

Time has two articles on the industry's history and its products: Julian W. S. Litten's

"Going in

Style-The Coffin: Its Place in Social History," and Richard Akerman's

"Picture Perfect: A

Cast-Iron Case." See also John L. Konefes and Michael K. McGee's "Old

Cemeteries, Arsenic, and Health Safety."

There can be little question that the embalmed

body is the cornerstone of this industry.

Without it there would be no need for all of the accoutrements for "viewings":

slumber rooms, elaborate coffins, or funerary apparels. Thus it is in the interest of

th e

industry for Americans to believe that a funeral without a body is like a marriage

ceremony without the bride or like a baptism without an infant. Cremations often mean

no open casket ceremonies. In our own class surveys,

students preferring burial were well over twice as likely to approve of "lying in state" than

those preferring to be cremated. Now, with more than one out of five deceased

Americans now being cremated (with rates being projected to increase to nearly one-third

by 2010--click here to see state rates) is it not

interesting to see casket companies writing

about cremation? (It should come as no surprise that such serious matters

invite humor and parody, such as funeralguy.com

with "a lighter look of the world of funerals, cemeteries, death and

the death care industries...") For a history of this means of body

disposal in America see Laura

Miller's review of Stephen Prothero's Purified by Fire in Salon.com.

The Internet Cremation Society bills

itself as "the number one visited cremation site in the world."

e

industry for Americans to believe that a funeral without a body is like a marriage

ceremony without the bride or like a baptism without an infant. Cremations often mean

no open casket ceremonies. In our own class surveys,

students preferring burial were well over twice as likely to approve of "lying in state" than

those preferring to be cremated. Now, with more than one out of five deceased

Americans now being cremated (with rates being projected to increase to nearly one-third

by 2010--click here to see state rates) is it not

interesting to see casket companies writing

about cremation? (It should come as no surprise that such serious matters

invite humor and parody, such as funeralguy.com

with "a lighter look of the world of funerals, cemeteries, death and

the death care industries...") For a history of this means of body

disposal in America see Laura

Miller's review of Stephen Prothero's Purified by Fire in Salon.com.

The Internet Cremation Society bills

itself as "the number one visited cremation site in the world."

The cremation industry is, not surprisingly, becoming increasingly

differentiated. There are companies, for instance, that will

turn cremains into jewelry. Eternal

Reefs will "Turn your Loved One's Ashes into a Living Coral Reef."

Space Services Inc.,

formerly Celestis, will launch one's remains

into space!

Other "insider" resources from the industry:

- Links galore from FUNERAL.COM

- Final Embrace--"Funeral home management and marketing advice from veterans of funeral service"

- Selected Independent Funeral Homes

- Links galore from Cremation Association of North America -- loaded with

information about state rates, historical trends, disposition, etc.

- International Cemetery and Funeral Association--

"Guardians of a Nation's Heritage"

- Everlife Memorials--memorials and

memorial products for people and pets alike (see also its

articles and

consumer guides)

-

HeavenlyDoor.com--a pre-need and funerary product locator site

(site disappeared by Dec. 2007)

- Arrangements.com--working in cooperation

with participating funeral homes with info on bereavement air fares, estate attorneys, florists,

appraisers, etc.

- National

Academy of Mortuary Sciences

-

Mortuary Schools in the U.S.

- HeavenlyDoor.com complete with funeral home and cemetery search engine

- San

Francisco College of Mortuary Science

- Funeral Service Education from

St. Louis Community College

- Abbott

and Hast Publishers, who bring you "Mortuary Management" magazine

and the "Funeral Monitor" newsletter

- National Casket Retailers Association

- W.R. Bennett Funeral Coaches--great images of vehicles for the final ride past and present

I guess it was to be expected: one can now receive online

funeral service consulting and make wholesale casket purchases from Zwisler Brothers "Tomorrow's

Cradle", ClassicMemorials.com,

and Funeralitems.com

. Frugalfuneral.com out

of Portland, OR, claims to have the only listing of funeral prices on the

web. Another funeral planning service, one targeting web-savvy, professional

Boomer males, is Funerals to Die

For--"discover how much fun making your arrangements can

be." To secure tomorrow's funeral at today's prices on the web,

go to Cooperative

Funeral Service in Great Britain.

I guess it was to be expected: one can now receive online

funeral service consulting and make wholesale casket purchases from Zwisler Brothers "Tomorrow's

Cradle", ClassicMemorials.com,

and Funeralitems.com

. Frugalfuneral.com out

of Portland, OR, claims to have the only listing of funeral prices on the

web. Another funeral planning service, one targeting web-savvy, professional

Boomer males, is Funerals to Die

For--"discover how much fun making your arrangements can

be." To secure tomorrow's funeral at today's prices on the web,

go to Cooperative

Funeral Service in Great Britain.

With industrialization came mass production--and mass

consumption to move the glut of goods. With the service orientation of

postindustrialism has come the customization of goods and services. Enter

Perpetua, Inc., one of whose funeral homes fashions various

realistic settings for the final farewell, including "Mama's Kitchen."

Another predictable phenomenon that has come to be is the electronic funeral. Claiming up to

be the first funeral home to broadcast a live funeral is Fergerson Funeral

Home. Funeral-Cast also

presents online services and has a directory of recent services for replay.

A new dimension of electronic memorials comes from Forever

Network, where the Hollywood elite, such as Rudolph

Valentino, and common folk are immortalized in text, photographs, and

movies.

ADDENDUMS

- Every worry about being buried alive? For a history of the fear see Salon.com's

Gary Kamiya's review

of Jan Bondeson's

Buried Alive: The Terrifying History of Our

Most Primal Fear

WARNINGS AND

GUIDES FOR THE CONSUMER

-

City of the Silent's A Consumer's Guide to Cemeteries and Funerals--answers

to all sorts of questions involving the industry, such as "Does the law

say that I must be embalmed?" and "Do I have to employ a funeral

director?"

-

FAMSA-Funeral Consumers Alliance (a federation of nonprofit consumer information societies)

- Funerals:

A Consumer Guide -- September 1991

- AARP's Funeral and Burial Planners Survey 1999

-

Dovetail-Resources for Funeral

Planning

-

DragoNet's Funeral Help Page--"funeral costs

are obscene!", with a "Funeral SCAM of the Month" section

-

The Internet Cremation Society

-

The Cremation

Consultant

-

Sympathy

and Funeral Arrangements

MEMORIAL

SOCIETIES

In 1992, the National Funeral Directors Association

held its 111th meeting here in San Antonio. A straw vote was taken of its

members' preferences for U.S. President that year. Bush was favored by

nearly two-thirds. One mortician said the votes were swayed by funeral

directors' concerns about Clinton's plans to more heavily tax Americans

making over $200,000 annually more. "Who in the hell doesn't make

$200,000 anymore?" he said.

There are a number of reasons why funeral homes have

one of the lowest failure rates of any business and why the funeral industry

produces one of the highest stock returns of any American industry. (And,

to boot, funeral homes are not required by federal law to file their financial

statements with the SEC.) Certainly one reason for the industry's success

involves Americans' death denials, often preventing any decision-making

until death occurs. Further, there is a profound ignorance about funerary

services and products, which include such costs as embalming (which, contrary

to popular opinion, is not normally required by law), funerary apparel,

usage fees for "slumber room" and chapel, a burial plot, the

grave liner, marker, newspaper obituaries, and the opening and closing

of the grave. As I wrote in Endings: A Sociology of Death and Dying:

When one enters a funeral home one enters ill prepared,

for this is not a K-Mart or dentist office, places for which one has prior

experience and knows "the game." One does not take a number nor

pushes a cart down aisles. Nor does one see samples of the quality of work

done. Instead, one enters at the mercy of a receptionist, who announces

to the staff that another performance is to begin and to "get into

role." The prospective customer, unfortunately, knows neither the

cues nor the script. She is then introduced to her funeral director. As

Turner and Edgley (1975:384) note, "the change of titles from `undertaker'

to `funeral director' has been perhaps the largest single clue to the dramaturgical

functions the industry now sees itself as performing. He is indeed a `director,'

controlling a dramatic production."

To make the drama more interesting, recall that this new

player is not oneself. Often a significant other's death has just occurred

and one has begun feeling the most awesome of emotions: grief. Experiencing

feelings that perhaps have never before been felt before and entering the

bereavement role, for which one may have no performance expectations, one

meets the man who "knows" about such things, the funeral director.

Our new widow is then led to a private "counseling" room, a diploma-filled

office looking much like that of any health care professional.

To counter the high cost of dying (average funeral

costs now exceed $5000), several funerary reform movements have arisen.

Among the most successful are the memorial societies that have sprung up

around the country. These groups promote simple services and basic products,

such as cremation, no embalming or viewing, and inexpensive wood caskets.

They negotiate with area funeral homes to provide their members economical

memorial services.

Check you local phone book to find the memorial society

in your area (don't expect to find it listed under "Funeral"

in your Yellow Pages). Even if one does not exist locally, one can still

receive the benefits of one by joining the Funeral

and Memorial Societies of America, Inc.. 6900 Lost Lake Road Egg Harbor,

WI 54209-9231 (414) 868-3136

For those in the San Antonio area, contact The San Antonio

Memorial Society at (210) 341-2213. In Houston, upon recommendations of the national society and to

make it easier to look up in the Yellow Pages, the name is now Funeral Consumers Alliance of Houston.

THE ALTERNATIVE-DEATH MOVEMENT

Reacting against the funeral industry's control over mortuary ritual, some individuals

seek to return control to families. Included in their agenda are home funerals

(including home preparation of the deceased, which is legal in all states but

New York, Louisiana, Indiana and Nebraska) and green burials. See Nancy

Rommelman's "Crying

and Digging: Reclaiming the Realities and Rituals of Death" (Los

Angeles Times, Feb. 6, 2005).

Reacting against the funeral industry's control over mortuary ritual, some individuals

seek to return control to families. Included in their agenda are home funerals

(including home preparation of the deceased, which is legal in all states but

New York, Louisiana, Indiana and Nebraska) and green burials. See Nancy

Rommelman's "Crying

and Digging: Reclaiming the Realities and Rituals of Death" (Los

Angeles Times, Feb. 6, 2005).

-

Final Passages--"dedicated to a compassionate and dignified alternative

to current funeral practices"

- PBS's

"A Family Undertaking"

-

Thresholds Home and Family-Directed Funerals

Return to Kearl's Death Index

Return to Kearl's Death Index

Rituals are condensed forms of experiences, tips of icebergs of meanings and social mechanisms for transformations.

These enactments of cultural belief systems go beyond mere ceremony, as Victor Turner noted when defining

ritual as "prescribed formal

behavior for occasions not given over to technological routine, having

reference to beliefs in invisible beings or powers" (From Ritual to

Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, p. 29) that preserve the structures

of both self and society. In rite-of-passage rituals, of which funerals are a type, old

used-up selves are shed so new ones can be instilled. With

increasing individualism and profoundly different times, traditional rituals may

no longer "work" and thus we see the rise of do-it-yourself

funerals.

Rituals are condensed forms of experiences, tips of icebergs of meanings and social mechanisms for transformations.

These enactments of cultural belief systems go beyond mere ceremony, as Victor Turner noted when defining

ritual as "prescribed formal

behavior for occasions not given over to technological routine, having

reference to beliefs in invisible beings or powers" (From Ritual to

Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, p. 29) that preserve the structures

of both self and society. In rite-of-passage rituals, of which funerals are a type, old

used-up selves are shed so new ones can be instilled. With

increasing individualism and profoundly different times, traditional rituals may

no longer "work" and thus we see the rise of do-it-yourself

funerals.