COLLECTIVE BEHAVIOR AND THE

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGIES OF SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Here

we will consider the most "macro" dimensions of social psychology, those social

forces arising out of the interactions of large numbers of individuals and

groups which, in turn, are the master templates patterning the cultural and

social orders. One cannot study the behaviors of individuals without devoting

some attention to the broader socio-cultural environments--their economic

structures, stratification orders, technological systems of communication and

transportation, family processes, demographics, and value systems-- structuring

their social lives.

Here

we will consider the most "macro" dimensions of social psychology, those social

forces arising out of the interactions of large numbers of individuals and

groups which, in turn, are the master templates patterning the cultural and

social orders. One cannot study the behaviors of individuals without devoting

some attention to the broader socio-cultural environments--their economic

structures, stratification orders, technological systems of communication and

transportation, family processes, demographics, and value systems-- structuring

their social lives.

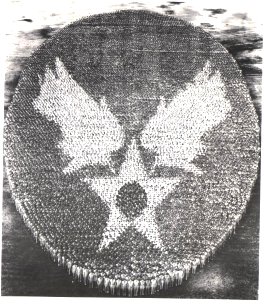

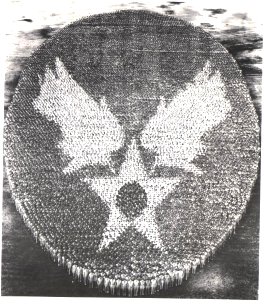

Humans have long been fascinated by the processes through which

collective social wholes emerge out of individuals' separate activities.

They have probably forever felt the sense of exhilaration and power of their

unity in numbers when pressed into crowds. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts in the image on the left. In this 1947 photograph

by E.O. Goldbeck, 21,765 members of the U.S. Army Air Force are fused into a

symbol of their group.

COLLECTIVE BEHAVIOR

AND SOCIAL

MOVEMENTS

By "collective behavior" social scientists

typically mean that realm of action not governed by the everyday rules and

expectations which normally shape social behavior:

Besides being large-scale social phenomena, sociologists' interest in their genesis and

development stem from the fact that they are major engines of social

change.

Collective action can be understood as the result of an

emerging collective definition of the situation.

This definition includes elements of shared cognitive belief (the "facts" that are

commonly defined as being real and relevant), emotional factors (such as the

personal needs being frustrated and the dominant emotion evoked), and the predominant

motivation of those present. How such a commonly-shared mindset

comes to be gets us into such topics as how information flows through social

networks (recall Stanley Milgram's "Small World" thesis, recently

mathematically

verified, that we are no more than six steps removed from any other person

on earth?) and connectivity opportunities provided by email and the

Web (also being explored in James Moody's Electronic

Small World Project and at Columbia University's Small World Research

Project).

Collective action can be understood as the result of an

emerging collective definition of the situation.

This definition includes elements of shared cognitive belief (the "facts" that are

commonly defined as being real and relevant), emotional factors (such as the

personal needs being frustrated and the dominant emotion evoked), and the predominant

motivation of those present. How such a commonly-shared mindset

comes to be gets us into such topics as how information flows through social

networks (recall Stanley Milgram's "Small World" thesis, recently

mathematically

verified, that we are no more than six steps removed from any other person

on earth?) and connectivity opportunities provided by email and the

Web (also being explored in James Moody's Electronic

Small World Project and at Columbia University's Small World Research

Project).

A century ago one of the first social science

investigations of collective action focused on the behavior of crowds. Gustave LeBon, in

The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1897), wrote of

the "crowd mind," emerging from anonymity and deindividuation (which often leads to

antisocial behavior), contagion (e.g., epidemic

hysteria, a variant of Functional Somatic Syndromes),

convergence (such as the Seattle

windshield pitting epidemic of 1954), and emergent norms.

Though contemporary social scientists have dismissed LeBon's "crowd mind," his antecedents

continue to influence social research. Indeed, individuals (whether crowd members or

observers) frequently act on the basis of their inferences about what the crowd "thinks, fears,

hates, and wants."

The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1897), wrote of

the "crowd mind," emerging from anonymity and deindividuation (which often leads to

antisocial behavior), contagion (e.g., epidemic

hysteria, a variant of Functional Somatic Syndromes),

convergence (such as the Seattle

windshield pitting epidemic of 1954), and emergent norms.

Though contemporary social scientists have dismissed LeBon's "crowd mind," his antecedents

continue to influence social research. Indeed, individuals (whether crowd members or

observers) frequently act on the basis of their inferences about what the crowd "thinks, fears,

hates, and wants."

The crowds that go mad--such as the 1921

Tulsa race riot (see also The

Nation's

story of events)--have long intrigued social scientists. (See Tony

Perez's Annotated

Bibliography on Riots and Protest.) These

intensely emotional mobs that violate the social norms and values have been both

agents of social change and targets of severe repression by agencies of social

control. Participants, anonymous and deindividualized and hypersensitive

to any emergent definition of the situation, may find themselves engaging in

acts of wanton destruction that they never envisioned nor intended.

Being major agents of social change, perhaps the

most-studied forms of collective behavior are social movements, such as the

American civil rights, anti-war, feminist, and environmental

crusades of recent

decades. These can arise, for instance, when cultural values become ambiguous

during times of social change or crisis, when people find themselves in

unanticipated situations, or when individuals' motives are similarly blocked. Such are the

occasions when novel shared definitions of the situation arise and a collectivity is formed,

experiences solidarity, and mobilizes for action.

Being major agents of social change, perhaps the

most-studied forms of collective behavior are social movements, such as the

American civil rights, anti-war, feminist, and environmental

crusades of recent

decades. These can arise, for instance, when cultural values become ambiguous

during times of social change or crisis, when people find themselves in

unanticipated situations, or when individuals' motives are similarly blocked. Such are the

occasions when novel shared definitions of the situation arise and a collectivity is formed,

experiences solidarity, and mobilizes for action.

Precisely how such collective action arises has likewise

received considerable theory and research. Neal Smelser, for instance,

develops such processes as:

- structural strain

- structural conduciveness

- generalized belief

- some precipitating factor

- mobilization of participants for action

- success or failure of social control mechanisms

A rich topic for research is the role of the photographer in triggering social movements.

Consider the role, for instance, of Lewis H. Hine is bringing about reform in child labor laws.

- Women

and Social Movements in the United States, 1775-1940 by Thomas Dublin &

Kathryn Kish Sklar (SUNY Binghamton)

- ASA

Section on Collective Behavior and Social Movements

- The American Social Movement Cultures (Washington State)

- Richard Kimber's

Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Other Social Movements (broken down by nation)

- Protest.Net--discover where protests are percolating across the U.S. and internationally

- WTO History Project,

from the University of Washington with a focus on the 1999 Seattle protests

- Lorry Britt

& David Heise, "From Shame to Pride in Identity Politics"

-

Kenneth Andres & Michael Biggs, "The Dynamics of Protest Diffusion: The 1960 Sit-In Movement in the American South"

- Nathan

Wolfson on the structural preconditions for anti-semitic mobilization

- Yahoo's social movements directory

- Prohibition

Materials

-

Underlying Causes of the LA Riots--Listserv Archive from the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute

of Public Affairs

- Pro-Life and

Pro-Choice Movements in the Abortion debate

INSTITUTIONAL PSYCHOLOGIES

Institutions are perceptual, cognitive, emotive and

behavioral systems--conventional domains of "you knows." As grammar

allows one to make sense of a string of words, so institutions provide

individuals with consensual ways for deriving meaning from their social

interactions. They also provide individuals routine ways for making decisions

and acting in various situations with various types of others. As Mary

Douglas observes in How Institutions Think (Syracuse University

Press, 1986:102), "the instituted community blocks personal curiosity,

organizes public memory, and heroically imposes certainty on uncertainty.

In marking its own boundaries it affects all lower level thinking, so that

persons realize their own identities and classify each other through community

affiliation."

From a more social perspective, institutions are social

housekeepers in that they program the routine services necessary for the

day-to-day functioning of the group. With social evolution, distinctive

institutions emerged to address the separate needs of society. For instance,

out of society's need for protection against external threats arose the

military; out of the social need for an informed and trained citizenry

emerged education; and out of the social need for moral consensus and restraint

of selfish impulses arose religion. Ideally these social needs addressed

simultaneously address the needs of individuals, such as the social need

for procreating the next generation of members matching the personal needs

for intimacy and connectedness in the institution of the family.

From a more social perspective, institutions are social

housekeepers in that they program the routine services necessary for the

day-to-day functioning of the group. With social evolution, distinctive

institutions emerged to address the separate needs of society. For instance,

out of society's need for protection against external threats arose the

military; out of the social need for an informed and trained citizenry

emerged education; and out of the social need for moral consensus and restraint

of selfish impulses arose religion. Ideally these social needs addressed

simultaneously address the needs of individuals, such as the social need

for procreating the next generation of members matching the personal needs

for intimacy and connectedness in the institution of the family.

From this social psychological perspective, the

methodological

tasks are to measure the way a given institution

- addresses the needs of both individuals and social

systems;

- shapes perception, beliefs, and cognition;

- induces various emotional experiences, such as the

feelings of awe and respect, love and hate;

- creates its own language, concepts, and metaphors;

- impacts identity: the bearing of its roles on the

self-concepts and esteem of its actors, its rites-of-passages, its demands

for biographical summaries and accountabilities;

- defines situations and creates settings for interaction;

- channels behavior, such as its encouragement of

risk-taking

or pro-social activities, restraint on sexual activity, or timing of activities;

- creates group dynamics, such as creating in-groups

and out-groups, and specifying roles for leaders and followers, and groupthink;

- spawns collective action and social movements;

- relates to other institutional systems of action and

thought.

To illustrate how institutions "work" consider the act of driving a car.

With these point in mind, consider the following findings

from "The Diminishing Divide-- American Churches, American Politics"

by The Pew Research Center For the

People and the Press. In several national surveys (the last conducted

in April 1996), Americans were asked for their views on the following

issues:

- The death penalty for persons convicted of murder.

(CAPPUN)

- President Clinton's decision to send 20,000 U.S. troops

to Bosnia as part of an international peacekeeping force. (BOSNIA)

- Allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. (HOMO

MARR)

- Which comes closer to your view? Abortion should be

generally available, ... but under stricter limits, ... against the law

except in cases of rape, incest, and to save the woman's life,... not permitted

at all. (ABORTION)

- Which comes closer to your view? The government should

do more to help needy Americans even if it means going deeper in debt.

The government today can't afford to do much more to help the needy. (GOVPOOR)

- Which comes closer to your view? This country should

do whatever it takes to protect the environment. This country has gone

too far in its efforts to protect the environment. (ENVIRON)

- Which comes closer to your view? Society has been

improved because women are now represented in the work place. Society made

a mistake in encouraging so many women with families to work. (WORKING

WOMEN)

For each issue respondents were also asked "Which

one of the following has had the biggest influence on your thinking on

this issue: 1) a personal experience; 2) the views of your friends and

family; 3) what you have seen or read in the media; 4) your religious beliefs;

5) your education; or 6) something else. Below, for each issue, are the

percentages of individuals reporting each influence to be the largest.

| ISSUE |

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE |

FRIENDS/FAMILY |

MEDIA |

RELIGION |

EDUCATION |

OTHER |

| CAPPUN |

13 |

6 |

21 |

18 |

21 |

18 |

| BOSNIA |

15 |

7 |

35 |

6 |

18 |

16 |

| HOMO MARR |

10 |

7 |

9 |

37 |

17 |

17 |

| ABORTION |

18 |

7 |

7 |

28 |

22 |

16 |

| GOVPOOR |

26 |

7 |

22 |

6 |

24 |

13 |

| ENVIRON |

22 |

3 |

24 |

3 |

36 |

10 |

| WORKING WOMEN |

45 |

8 |

7 |

4 |

23 |

11 |

As can be seen, for only two of the seven issues were

Americans' attitudes most influenced by personal experiences. The media,

for instance, was the greatest influencer of orientations toward capital

punishment and America's Bosnia interventions, while religion was the greatest

shaper of opinions toward homosexual marriages and abortion.

To more easily gauge the relative influence of these

various sources of opinion we can standardize each row, dividing each percentage

by the largest percentage therewithin. For instance, 28 percent of Americans

claimed that religion was the greatest shaper of their opinions toward

abortion. Dividing each percentage in this row by .28 we find that Americans

are only one-quarter as likely to cite the media (and the views of family

and friends) as they are to cite religion as the greatest influence on

their abortion attitudes.

| ISSUE |

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE |

FRIENDS/FAMILY |

MEDIA |

RELIGION |

EDUCATION |

OTHER |

| CAPPUN |

.62 |

.29 |

1.0 |

.86 |

1.0 |

.86 |

| BOSNIA |

.43 |

.20 |

1.0 |

.17 |

.51 |

.46 |

| HOMO MARR |

.27 |

.19 |

.24 |

1.0 |

.46 |

.46 |

| ABORTION |

.64 |

.25 |

.25 |

1.0 |

.79 |

.57 |

| GOVPOOR |

1.0 |

.27 |

.85 |

.23 |

.92 |

.50 |

| ENVIRON |

.61 |

.08 |

.67 |

.08 |

1.0 |

.28 |

| WORKING WOMEN |

1.0 |

.18 |

.16 |

.09 |

.51 |

.24 |

| MEAN INFLUENCE |

.65 |

.21 |

.60 |

.49 |

.74 |

.48 |

Reflecting on the "Mean Influence" row on

the bottom, the institutional bearing of Americans' attitudes and values

cannot be denied. The concerns of critics of the messages delivered by

mass media and educational curricula appear well-grounded as the influence

of these two institutions rival that of personal experience.

THE

SOCIAL

PSYCHOLOGY OF INEQUALITY

inequality among men [is] a rich source of much that

is evil, but also of everything that is good.

--Kant

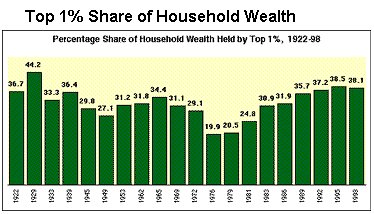

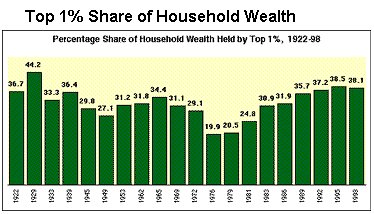

Consider the concept of "The American

Dream":

the expectation of achieving a higher standard of living than one's parents.

Has this expectation changed historically? Has it changed historically

more so for some groups--social classes, minorities, or women--than for

others (or might the notion historically referred only to the condition

of white middle- class males)? What are the social psychological implications

of not holding this belief?

Individuals' positions in the stratification orders

of sex, race, and

social

class determine the language the speak, their values, happiness, self-esteem,

sense of personal efficacy, physical and mental health, rate of aging and

life-expectancy, sexual activities, childrearing practices, and nature

of their work.

THOUGHT PROBLEM

Suppose that you are a member of a dominant group.

What social psychological tactics would you use to ensure that your "social

lessers" remain in their place?

EXPLORING AMERICANS' ATTRIBUTIONS OF WHY THE POOR ARE

POOR

In the 1990 NORC General Social Survey, Americans were

asked why there are poor people in this country. Two questions dealt with

internal loci of control (e.g., they blame the victims): People

are poor because of: Loose morals and drunkenness, and Lack of effort by

the poor themselves. Two deal with external loci (e.g., they locate

the cause in society): Failure of society to provide good schools for many

Americans, and Failure of industry to provide enough jobs. Out of these

questions was created a scale of poverty attributions, where 1=society's

fault, 2=both social and personal faults, and 3=self-fault. Not surprisingly,

those identifying themselves as members of the lower class are most likely

to see poverty being society's fault (43%) than are the other classes,

but there is virtually no difference in attributions of the working, middle,

and upper classes (27% of whom blame society). Women are slightly more

to blame society (30%) than men (26%), as are those 18-29 years of age

(32%) compared to those 70 and older (19%).

Click to see:

Related resources:

- T.R. Young's "The Contributions of Karl

Marx to Social Psychology"

- Dimostenis

Yagcioglu's "Psychological Explanations of Conflicts Between Ethnocultural

Minorities and Majorities"

- Explorations in Social Inequality

THE SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OF

RELIGION

Decency is veiled from sight; indecency is exposed

to view. Scenes of evil attract packed audiences; good words scaredly find

any listeners. It is as if purity should provoke a blush, and corruption

give ground for pride. But where else should this happen but in devils'

temples, in the resorts of delusion?

--St.

Augustine

According to a 1995

Gallup Survey, virtually all Americans (96%) say they believe in God

or a universal spirit, and most Americans (88%) say religion is important

in their lives. Certainly any description of American

Exceptionalism must include Americans' profound religiosity and their

faith in the existence of an afterlife. To see how your personal beliefs match up with those of twenty-six

world religions try the Religion

Selector by SelectSmart.com and SpeakOut.com.

According to a 1995

Gallup Survey, virtually all Americans (96%) say they believe in God

or a universal spirit, and most Americans (88%) say religion is important

in their lives. Certainly any description of American

Exceptionalism must include Americans' profound religiosity and their

faith in the existence of an afterlife. To see how your personal beliefs match up with those of twenty-six

world religions try the Religion

Selector by SelectSmart.com and SpeakOut.com.

RELIGION'S ROLE IN ADDRESSING THE NEEDS OF

SELF AND SOCIETY

In numerous ways, religion acts as a shock absorber

that cushions the inevitable tensions between self and society. Social

frustrations must be resolved; the incongruities between personal desires

and social needs must be explained. Social order may well require individuals' absolute faith in

the order, meaningfulness, and justice of social life. Religious faith is a potent source of

human motivation, whether directed toward orthodoxy or

fanaticism.

In numerous ways, religion acts as a shock absorber

that cushions the inevitable tensions between self and society. Social

frustrations must be resolved; the incongruities between personal desires

and social needs must be explained. Social order may well require individuals' absolute faith in

the order, meaningfulness, and justice of social life. Religious faith is a potent source of

human motivation, whether directed toward orthodoxy or

fanaticism.

Considering the needs of

selves and societies addressed by religion, let's first investigate the extent

to which religiosity contributes to the happiness of individuals.

As can be seen, when controlling for Americans' age and

education, those who report being "strongly" religious are

significantly more likely

to be "very happy" than are their less religious counterparts--

particularly among those 18-30 and those 45-64 years of age.

In addition to emotional health, religion contributes to

physical well-being as well, evidenced by Mormons' prohibitions against alcohol, tobacco and

caffeine. In the October 1997 issue of The International Journal of Psychiatry in

Medicine is reported a study by Harold Koenig and Harvey Cohen of 1,718 older North

Carolinians. They found that those who attended religious services at least once a week were

significantly less likely to have high levels of interleukin-6, an immune-system protein

implicated with a number of diseases, in their bloodstreams. Perhaps it should not be

surprising that one-quarter of Americans report using prayer as a form of health care. For

other studies, check out The National Institute for

Healthcare Research ("Bridging the Gap Between Spirituality and Health").

Click here to see influence

of religion on Americans' outlooks toward science and belief in the theory of evolution.

It is in society's interest that individuals voluntarily

become involved in its groups and organizations, particularly in a democratic

society such as ours. Being so "plugged into" the social order

not only keeps individuals out of mischief but intertwines personal motivations

with group objectives. Over the years, the NORC General Social Surveys

have asked Americans if they are members of fraternal groups, service clubs,

political clubs, school service groups, farm organizations, professional

societies, and the like. As can be seen, even

when controlling for age and education, religiosity significantly increases

the likelihood of individuals belonging to four or more of the sixteen

groups inquired of--particularly for those with at least some post-secondary

education. And, as developed elsewhere,

religiosity is significantly related to volunteerism.

It is in society's interest that individuals voluntarily

become involved in its groups and organizations, particularly in a democratic

society such as ours. Being so "plugged into" the social order

not only keeps individuals out of mischief but intertwines personal motivations

with group objectives. Over the years, the NORC General Social Surveys

have asked Americans if they are members of fraternal groups, service clubs,

political clubs, school service groups, farm organizations, professional

societies, and the like. As can be seen, even

when controlling for age and education, religiosity significantly increases

the likelihood of individuals belonging to four or more of the sixteen

groups inquired of--particularly for those with at least some post-secondary

education. And, as developed elsewhere,

religiosity is significantly related to volunteerism.

For instance, strongly religious individuals

were found to be two-thirds more likely (45% vs. 27%) to have volunteered for two or more

causes over the previous year. This religiosity effect is most pronounced among the most highly

educated: among those with four or more years of college (who were three times more likely

than high school dropouts to be high volunteers), the strongly religious were three-quarters

more likely (71% vs. 45%) to have volunteered for two or more causes.

For instance, strongly religious individuals

were found to be two-thirds more likely (45% vs. 27%) to have volunteered for two or more

causes over the previous year. This religiosity effect is most pronounced among the most highly

educated: among those with four or more years of college (who were three times more likely

than high school dropouts to be high volunteers), the strongly religious were three-quarters

more likely (71% vs. 45%) to have volunteered for two or more causes.

- From the Independent Sector and the

National Council of Churches:

Faith and Philanthropy: The Connection Between Charitable Behavior and Giving to Religion (2002)

RELIGION'S ROLE IN SHAPING AMERICANS' MORAL

OUTLOOKS

Click here to see religion's role in shaping Americans'

attitudes toward some of the moral issues of our times:

Click here to see religion's role in shaping Americans'

attitudes toward some of the moral issues of our times:

- Michael

Nielson's Psychology of Religion Page, including full text of William James's

The Varieties of

Religious Experience

- Diana Eck's (Harvard) The Pluralism

Project

- The American Religious

Experience Project, a consortium of UWV, UNC, LA State, AZ State,

Barnard-Columbia, and Franklin and Marshall

- Religion Online--over 900 articles

& chapters by religious scholars

- From PEW/Public Agenda "For Goodness Sake"

--a survey released in 2003 finding the American public strongly equates religion with

personal ethics and views faith as an antidote to the nation's moral problems

- Rutgers Anthropology/Sociology of Religion links

- Adherents.com statistics galore on over 4000 religions

- Hartford Institute for

Religion Research

- Jeffrey Hadden's New Religious

Movements Page

- American Religion Data Archive (Purdue):

downloadable files in ASCII, SPSS, and MicroCase formats, with such studies as "Anti-Semitism

in the U.S., 1981"

- Beliefnet.com--"We all believe in something."

- The Pluralism Project--"Our mission is to help Americans engage with the realities of

religious diversity through research, outreach, and the active

dissemination of resources."

- Religion & Ethics Newsweekly

- Weberian

Sociology of Religion

RELIGION AS ANTIDOTE TO ANOMIE AND PERCEIVED CRISES OF

MORALITY

- Briane

Turley's American Religion Links

- Case study: American Guardian: "America's Frontline Defense

Against Perversion"

- Ronald

Fagan on religion's role in restraining excessive individualism in Habits

of the Heart

RELIGION AS ANTIDOTE TO CRISES OF THE LIFESPAN

- UCLA's Higher Education Research Institute's National Study of

of College Students' Search for Meaning and Purpose--results of the 2004 survey of more than 112,000

students from 236 colleges

RELIGION AS MECHANISM OF OPPRESSION AND LEGITIMATOR OF VIOLENCE

- Donald G. Mathews, "The Southern Rite of Human Sacrifice" in

The Journal of Southern Religion

THE SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OF

CULTS

THE SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OF WORK

AND LEISURE

When people meet for the first time, a question that

invariably arises is, "What do you do for a living?" We believe

that to know another person's line of work is to have a highly predictive

framework for inferring his or her social status, interpersonal traits

and skills, value orientations, personal interests, and even personality

type. So central is work to establishing one's social that King John of

England proclaimed that people must use surnames pertaining to their trade.

As populations were growing rapidly and the social system was becoming

increasingly specialized, it was no longer practical to refer to others

by their first names (even when coupled with one's residence, such as Edward-of-Dover).

What better way to index other selves than by what they do? Those who made

carts became Cartwrights and Wainwrights; metal workers became Smiths;

and Shepard became the surname of people who tended sheep.

When people meet for the first time, a question that

invariably arises is, "What do you do for a living?" We believe

that to know another person's line of work is to have a highly predictive

framework for inferring his or her social status, interpersonal traits

and skills, value orientations, personal interests, and even personality

type. So central is work to establishing one's social that King John of

England proclaimed that people must use surnames pertaining to their trade.

As populations were growing rapidly and the social system was becoming

increasingly specialized, it was no longer practical to refer to others

by their first names (even when coupled with one's residence, such as Edward-of-Dover).

What better way to index other selves than by what they do? Those who made

carts became Cartwrights and Wainwrights; metal workers became Smiths;

and Shepard became the surname of people who tended sheep.

Of all the institutionalized arenas of human activity,

work is the most central, both sociologically and psychologically. From

a macro perspective, work is a way of keeping social actors "out of

mischief" by harnessing and coordinating their energies to produce

socially necessary goods and services. The products of work become the

basis of trade, which brings cultures into contact with each other, thereby

providing opportunities for social innovation.

Of all the institutionalized arenas of human activity,

work is the most central, both sociologically and psychologically. From

a macro perspective, work is a way of keeping social actors "out of

mischief" by harnessing and coordinating their energies to produce

socially necessary goods and services. The products of work become the

basis of trade, which brings cultures into contact with each other, thereby

providing opportunities for social innovation.

From a micro perspective, work satisfies a broad spectrum

of individual needs, such as the needs for solidarity and a feeling of

self-worth. One way to appreciate this function of is to study those who

lack it: the unemployed and unemployable, those who have been fired and

laid off, and retired people. In many ways these individuals become nonpersons;

their activities are no longer perceived as wholly legitimate, since only

through working is one generally seen as contributing to the social system.

The centrality to individuals' needs is further evidenced by the movements

for equal opportunity for women and minorities.

Topic ideas in the social psychology of work:

- professional argots and jargon

(e.g., legalese, bureaucratese)

- how do organizations harness worker loyalties?

- the centrality of work role to individuals' identities and lives

- the connection between work satisfactions and overall happiness

with life--and how this varies across societies, the lifespan, and between

the sexes

- what does "success" in work mean to individuals? (e.g.,

income, respect and recognition of superiors and/or peers, having control

over work content and schedules, etc.)

- what kinds of selves are spawned by capitalism vs. socialism?

- distributive justice and workplace ethics; see Public Agenda's 2004

study "A

Few Bad Apples? An Exploratory Look at What Typical Americans Think about

Business Ethics Today"

- the impacts of retirement

on identity

- the bifurcated work-self/private-self. In 1990s there emerged what was known as the

California

self,

a new Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: the corporate dictator who morphs

into a loving parent and hospice volunteer

- Economic

Beliefs

and Behaviour--downloadable discussion papers

- How did the Wall Street Crash of 1929 occur? Play the market with

this interactive simulation.

- Eva Bertram and Kenneth

Sharpe's "Capitalism, Work and Character"

- Robert Merton's

"Bureaucratic Structure and Personality"

- David Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald, "Well-being, Insecurity, and the Decline of American Job Satisfaction" (1999, pdf format)

- The Temporalities of

Work and Leisure

INDUSTRIAL PSYCHOLOGY

- Working papers from the

Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies at Cornell's School of Industrial and Labor

Relations

- The Society for Industrial and Organizational

Psychologist

- Journal

of Applied Behavior Analysis

CONSUMERISM

P.S. It is my observation that too many of us are spending

money we haven't earned to buy things we don't need to impress people we

don't like.

--H. Jackson Brown's mother (from "P.S. I Love

You")

During the winter of '94-95 throughout the Midwest there

appeared the following

mall advertisement: "Shop like you mean it." What does this supposed

to mean?

During the winter of '94-95 throughout the Midwest there

appeared the following

mall advertisement: "Shop like you mean it." What does this supposed

to mean?

The mass production wrought by industrialization required

mass consumption, which brings us to the social psychology of materialism

and abundance. How are individuals socialized and conditioned to consume? One

place is in the schools. Check out Arizona State University's

Commercialism in Education

Research Unit, the Center

for Commercial-Free Public Education, and

Schools Inc. from

PBS's NOW.

-

Collection of articles and essays on advertising

- Mass consumerism requires a buy-now-pay-later mindset. Check out PBS Frontline's

Secret History of the Credit Card

- Temples of Consumption: Shopping Malls as Secular

Cathedrals, an essay written with Beth Gill

- "Identity and Desire in Consumption:

Interactions between Industry and Consumers by the Use of Commodities", by Mineo Hattori (1997)

-

Inconspicuous consumption: the sociology of

consumption and the environment, by Elizabeth Shove and Alan Warde

- Don

Slater's "Researching Consumer Cultures" page (with sizable

bibliography)

- Signaler "Analyzing

commercials and advertisements. How products get their meaning and the way

they signify."

- Richard Taflinger's Taking

ADvantage

- John

W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History

- Celebrating 75 Years of Supermarkets: 1930-2005

facts and figures from the Food Marketing Institute

- NPD Group "leading international provider of marketing information...[tracking]

retail and e-commerce sales plus consumer behavior and attitudes"

- Bad Fads

Museum--Look at what Madison Avenue has made us consume

- For further mirth, check out a collection of bad ads at

The Gallery of the Absurd

- Consumerism gotten you down? Check out

Overcoming Consumerism: Citizen-Activist's Anti-consumerism site

- Have a complaint? Place to gripe is eComplaints.com--"a better way to complain"

- Want to see a future tool of retailers to know precisely what button of yours to push?

Check out IBM's BlueEyes software to

determine individuals' physical, emotional or informational states by

analyzing video and audio information. Other

researchers of consumers' minds (and impulses):

-

Links to Consumer Psychology Research

- Ipsos --"features a collection of behavioral tracking products and services that

help clients throughout a broad range of industries learn how to marry

consumers' behaviors with their attitudes."

- The American

Marketing Association

- Public Relations

Society of America Home Page

- International

Advertising Association

- The Institute For Retail Studies

- Advertising Age

- Journal of Material Culture

THE SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OF MASS MEDIA

Return to Social Psychology

Index

Return to Social Psychology

Index

Here

we will consider the most "macro" dimensions of social psychology, those social

forces arising out of the interactions of large numbers of individuals and

groups which, in turn, are the master templates patterning the cultural and

social orders. One cannot study the behaviors of individuals without devoting

some attention to the broader socio-cultural environments--their economic

structures, stratification orders, technological systems of communication and

transportation, family processes, demographics, and value systems-- structuring

their social lives.

Here

we will consider the most "macro" dimensions of social psychology, those social

forces arising out of the interactions of large numbers of individuals and

groups which, in turn, are the master templates patterning the cultural and

social orders. One cannot study the behaviors of individuals without devoting

some attention to the broader socio-cultural environments--their economic

structures, stratification orders, technological systems of communication and

transportation, family processes, demographics, and value systems-- structuring

their social lives.

The Rick A. Ross Institute for the Study of Destructive Cults, Controversial Groups and Movements

The Rick A. Ross Institute for the Study of Destructive Cults, Controversial Groups and Movements

Of all the institutionalized arenas of human activity,

work is the most central, both sociologically and psychologically. From

a macro perspective, work is a way of keeping social actors "out of

mischief" by harnessing and coordinating their energies to produce

socially necessary goods and services. The products of work become the

basis of trade, which brings cultures into contact with each other, thereby

providing opportunities for social innovation.

Of all the institutionalized arenas of human activity,

work is the most central, both sociologically and psychologically. From

a macro perspective, work is a way of keeping social actors "out of

mischief" by harnessing and coordinating their energies to produce

socially necessary goods and services. The products of work become the

basis of trade, which brings cultures into contact with each other, thereby

providing opportunities for social innovation.