Marvene is a poor and unemployed elderly woman who lost her shack to

foreclosure in 2008.

That's after Marvene stole over $100,000 when she refinanced her shack with a

subprime mortgage in 2007.

Marvene wants to steal some more or at least get her shack back for free.

Both the Executive and Congressional branches of the U.S. Government want to

give more to poor Marvene.

Why don't I feel the least bit sorry for poor Marvene?

Somehow I don't think she was the victim of unscrupulous mortgage brokers and

property value appraisers.

More than likely she was a co-conspirator in need of $75,000 just to pay

creditors bearing down in 2007.

She purchased the shack for $3,500 about 40 years ago ---

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123093614987850083.html

Marvene Halterman, an unemployed Arizona woman with a

long history of creditors, took out a $103,000 mortgage on her 576

square-foot-house in 2007. Within a year she stopped making payments. Now the

investors with an interest in the house will likely recoup only $15,000.

The Wall Street Journal slide show

of indoor and outdoor pictures ---

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123093614987850083.html#articleTabs%3Dslideshow

Jensen Comment

The $15,000 is mostly the value of the lot since at the time the mortgage was

granted the shack was virtually worthless even though corrupt mortgage brokers

and appraisers put a fraudulent value on the shack. Bob Jensen's threads on

these subprime mortgage frauds are at

http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/2008Bailout.htm

Probably the most common type of fraud in the Savings and Loan debacle of the

1980s was real estate investment fraud. The same can be said of the 21st Century

subprime mortgage fraud. Welcome to fair value accounting that will soon have us

relying upon real estate appraisers to revalue business real estate on business

balance sheets ---

http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/Theory01.htm#FairValue

CEO to his accountant: "What is our net earnings this year?"

Accountant to CEO: "What net earnings figure do you want to report?"

The sad thing is that Lehman, AIG, CitiBank, Bear Stearns, the Country Wide subsidiary of Bank America, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, etc. bought these

subprime mortgages at face value and their Big 4 auditors supposedly remained unaware of the millions upon millions of valuation frauds in the investments. Does professionalism in auditing have a stronger stench since Enron?

Where were the big-time auditors? --- http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/2008Bailout.htm#AuditFirms

The Rest of the Story

"Would You Pay $103,000 for This Arizona Fixer-Upper? That Was Ms. Halterman's Mortgage on It; 'Unfit for Human Occupancy,' City Says," by Michael M. Phillips, The Wall Street Journal, January 3, 2008 --- http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123093614987850083.html

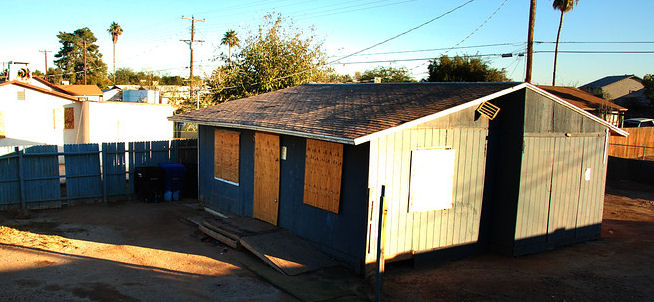

The little blue house rests on a few pieces of wood and concrete block. The exterior walls, ravaged by dry rot, bend to the touch. At some point, someone jabbed a kitchen knife into the siding. The condemnation notice stapled to the wall says: "Unfit for human occupancy."

The story of the two-bedroom, one-bath shack on West Hopi Street, is the story of this year's financial panic, told in 576 square feet. It helps explain how a series of bad decisions can add up to the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Less than two years ago, Integrity Funding LLC, a local lender, gave a $103,000 mortgage to the owner, Marvene Halterman, an unemployed woman with a long list of creditors and, by her own account, a long history of drug and alcohol abuse. By the time the house went into foreclosure in August, Integrity had sold that loan to Wells Fargo & Co., which had sold it to a U.S. unit of HSBC Holdings PLC, which had packaged it with thousands of other risky mortgages and sold it in pieces to scores of investors.

Today, those investors will be lucky to get $15,000 back. That's only because the neighbors bought the house a few days ago, just to tear it down.

At the center of the saga is the 61-year-old Ms. Halterman, who has chaotic blond-gray hair, a smoky voice and an open manner both gruff and sweet. She grew up here, working at times as a farm hand, secretary, long-haul truck driver and nurse's aide.

In time, the container of vodka-and-grapefruit she long carried in her purse got the better of her. "Hard liquor was my downfall," she says.

Ms. Halterman says she had her last drink on Jan. 3, 1996. These days, her beverage of choice is Pepsi.

She collects junk. Her yard at the West Hopi house was waist-high in clothes, tires, laundry baskets and broken furniture. In June, the city issued a citation for what the enforcement officer described as "an exorbitant amount of rubbish/debris/trash."

Ms. Halterman also collects people. At one time, she says, 23 people were living in the tiny house or various ramshackle outbuildings.

Her circle includes grandchildren, an old friend who lost her own home to foreclosure, a Chihuahua, and the one-year-old child of a woman Ms. Halterman's former foster-daughter met in jail.

In the mail recently, she noticed a newsletter sent by a state agency with an article titled "Raising Children of Incarcerated Parents, Part I."

"I need to read that one," she said aloud to herself.

She keeps the children in line with cuddles and mock threats. "You better put that shirt on, or that cop will come and take you to jail," she tells one. Another, whose father is in prison, was born with a heart problem related to his mother's drug use, Ms. Halterman says. She patiently nursed him to health.

Journal Community Discuss: How can mortgage lenders better assess risks?"It took me forever to get him past 15 lbs.," she recalls.

Ms. Halterman hasn't had a job for about 13 years, she says. She receives about $3,000 a month from welfare programs, food stamps and disability payments related to a back injury.

"I may not have everything I want, but I have everything I need," she says.

Four decades ago, when she bought the West Hopi Street house for $3,500, Avondale was a small town built around cotton farms. From 2000 to 2005, the heart of the housing boom, it doubled in size to 70,000 residents.

Today, one in nine Avondale houses is in foreclosure or close to it.

Her lender, Integrity, was one of a flurry of small mortgage firms that sprang up nationwide during the boom, using loans from big banks to generate mortgages to resell to larger financial institutions. Whereas traditional mortgage lenders profit by collecting borrowers' monthly payments, Integrity made its money on fees and commissions.

The company was owned by Barry Rybicki, 37, a former loan officer who started it in 2003. Of the boom years, he says: "If you had a pulse, you were getting a loan."

When an Integrity telemarketer called Ms. Halterman in 2006, she was cash-strapped, owing $36,605 on a home-equity loan. The firm helped her get a $75,500 credit line from another lender.

Ms. Halterman used it to pay off her pickup, among other things. But soon she was struggling again.

In early 2007, she asked Integrity for help, Mr. Rybicki's records show. This time, Integrity itself provided a $103,000, 30-year mortgage. It had an adjustable rate that started at 9.25% and was capped at 15.25%, according to loan documents.

It was one of 197 loans Integrity originated last year, totaling almost $47 million.

For a $350 fee, an appraiser hired by Integrity, Michael T. Asher, valued the house at $132,000. Mr. Asher says although he didn't personally believe the house was worth that much, he followed standard procedures and found like-sized homes nearby that had sold in that price range in 2006.

"I can't appraise it for the future," Mr. Asher says. "I appraise it for that day."

T.J. Heagy, a real-estate agent later hired to sell the property, says he can find only one comparable house that sold nearby in 2007, for $63,000.

At closing, on Feb. 26, 2007, Integrity collected $6,153 in underwriting, broker, loan-origination, document, application, processing, funding and flood-certification fees, mortgage documents show. A few days later, Integrity transferred the loan to Wells Fargo, earning $3,090 more, Mr. Rybicki says.

Kevin Waetke, of Wells Fargo Home & Consumer Finance Group, said in a written statement that "it appears that the appraisal ... confirms that the property values were fully supported at the time the loan closed."

Mr. Rybicki says neither he nor his loan officer ever saw the blue house. When shown a picture last month, he said: "Wow."

"When you have 50 employees, as much as you are responsible for holding their hands, you just can't," Mr. Rybicki says.

After the fees and her other debts were paid, Ms. Halterman walked away from closing with $11,090.33.

Ms. Halterman says she spent it on new flooring, a fence, minor repairs and food. "No steak or lobster," she says, "hamburger and chicken."

Soon the money was gone.

Within a few months she grew worried the rickety house wasn't safe for children. She moved to a rental nearby. Her son Leslie Merritt took up residence at West Hopi Street and assumed responsibility for the $881 monthly payments.

When Wells Fargo sold Ms. Halterman's loan to London-based HSBC, it got bundled with 4,050 other mortgages and used as collateral for a security issued in July 2007. More than 85% of the mortgages were, like Ms. Halterman's, "subprime" loans to borrowers with blemished credit, according to Tom Atteberry of First Pacific Advisors LLC, a Los Angeles investment-management company.

Credit-ratings firms Standard & Poor's and Moody's Investors Service gave the new security their top "triple-A" ratings, which suggested investors were extremely likely to get their money back plus interest. S&P declined to explain its assessment. A Moody's spokesman didn't respond to requests for comment.

Thus was Ms. Halterman's diminutive blue house tossed into the immense sea of mortgage-backed securities that would eventually imperil the U.S. financial system. Some $4.1 trillion in American mortgages were put into securities such as these between 2005 and 2006, including $1.6 trillion in subprime or other high-risk home loans, according to Inside Mortgage Finance, a trade publication.

Among other investors, the Teachers' Retirement System of Oklahoma bought $500,000 of the new security, according to chief investment officer Bill Puckett. Also buying in was bond-giant Pacific Investment Management Co., which declined to comment.

Soon, Ms. Halterman's son, Mr. Merritt, says he stopped paying the mortgage. He had slipped back into his methamphetamine addiction. "I lost interest in pretty much everything except my habit and the girl I was seeing," he says. Mr. Merritt is now in prison for trafficking in stolen copper pipe.

In January, Ms. Halterman stepped back in and made the last mortgage payment. Foreclosure began in May. September brought eviction.

Ms. Halterman says she wishes she had never taken out the first home-equity loan. "I felt like I needed it," she says. "In retrospect, I needed my a -- kicked."

Other loans backing the HSBC-issued security were souring, as well. As of November, 25% were foreclosed, in the foreclosure process or at least a month delinquent, Mr. Atteberry says.

HSBC declined to comment.

Mr. Rybicki gave up his mortgage-banking license in September. He now works for a venture-capital firm.

"The banks have part of the blame," Mr. Rybicki says of the housing bubble. "I think we have part of the blame. We were part of the system. So does the consumer."

Wells Fargo, which serviced the West Hopi Street loan, boarded up the house and hauled away the debris. And this past Monday, the property sold for $18,000 to Daniel and Delia Arce, who live next door in a tidy brick rambler. After expenses, investors in the mortgage-backed security will probably divide up no more than $15,000 in proceeds.

A few weeks ago, Mr. Arce asked Mike Summers, a city code-enforcement officer, whether a permit was required to raze the blue house.

"Yes," Mr. Summers replied, "but all you need is the big, bad wolf to come out and huff and puff."

September 30, 1999

By STEVEN A. HOLMES

In a move that could help increase home ownership rates among minorities and low-income consumers, the Fannie Mae Corporation is easing the credit requirements on loans that it will purchase from banks and other lenders.

The action, which will begin as a pilot program involving 24 banks in 15 markets -- including the New York metropolitan region -- will encourage those banks to extend home mortgages to individuals whose credit is generally not good enough to qualify for conventional loans. Fannie Mae officials say they hope to make it a nationwide program by next spring.

Fannie Mae, the nation's biggest underwriter of home mortgages, has been under increasing pressure from the Clinton Administration to expand mortgage loans among low and moderate income people and felt pressure from stock holders to maintain its phenomenal growth in profits.

In addition, banks, thrift institutions and mortgage companies have been pressing Fannie Mae to help them make more loans to so-called subprime borrowers. These borrowers whose incomes, credit ratings and savings are not good enough to qualify for conventional loans, can only get loans from finance companies that charge much higher interest rates -- anywhere from three to four percentage points higher than conventional loans.

''Fannie Mae has expanded home ownership for

millions of families in the 1990's by reducing down payment

requirements,'' said Franklin D. Raines, Fannie Mae's chairman and chief

executive officer. ''Yet there remain too many borrowers whose credit is

just a notch below what our underwriting has required who have been

relegated to paying significantly higher mortgage rates in the so-called

subprime market.''

Demographic information on these borrowers is sketchy. But at least one

study indicates that 18 percent of the loans in the subprime market went

to black borrowers, compared to 5 per cent of loans in the conventional

loan market.

In moving, even tentatively, into this new area of lending, Fannie Mae is taking on significantly more risk, which may not pose any difficulties during flush economic times. But the government-subsidized corporation may run into trouble in an economic downturn, prompting a government rescue similar to that of the savings and loan industry in the 1980's.

''From the perspective of many people, including me, this is another thrift industry growing up around us,'' said Peter Wallison a resident fellow at the Americ an Enterprise Institute. ''If they fail, the government will have to step up and bail them out the way it stepped up and bailed out the thrift industry.''

Under Fannie Mae's pilot program, consumers who qualify can secure a mortgage with an interest rate one percentage point above that of a conventional, 30-year fixed rate mortgage of less than $240,000 -- a rate that currently averages about 7.76 per cent. If the borrower makes his or her monthly payments on time for two years, the one percentage point premium is dropped.

Fannie Mae, the nation's biggest underwriter of home mortgages, does not lend money directly to consumers. Instead, it purchases loans that banks make on what is called the secondary mark et. By expanding the type of loans that it will buy, Fannie Mae is hoping to spur banks to make more loans to people with less-than-stellar credit ratings.

Bob Jensen's threads on the subprime mortgage frauds are at http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/2008Bailout.htm