|

|

The world of my young sons features two working parents, day care, Nintendo, shopping malls, microwave meals, and a suburban neighborhood filled with kids. They are raised to assume that if one pushes the right buttons the garage door will open or the television comes on, that Dad can be talked to--even though he is miles away--from Mom's car phone, that Grandma can be visited in two hours even though she lives 600 miles away, and that people have walked on the moon and returned home at speeds of 25,000 miles an hour.

Their grandparents were raised in a society of farms and small towns, in which children often worked to help support the family by milking the cows or selling loaves of bread for a dime apiece. They were raised to assume that the human voice can travel via radio waves, that some people have telephones but must wait until others are off the community line to place a call, that grandparents living 600 miles away can be reached in a day and a half by train, and that speeds of 200 miles an hour have been reached in airplanes.

Then there's the perspective of the boys' great-grandparents, who were born in the late nineteenth century when Victoria was the queen of England, or in the early twentieth century during the presidency of Teddy Roosevelt. Most people entered the world not in hospital delivery rooms but in the family home by the light of a kerosene lamp. Most were raised on remote farms on the plains and in the Far West, where they played with imaginary friends, socialized during weekend visits to town, and received their formal education from their parents.

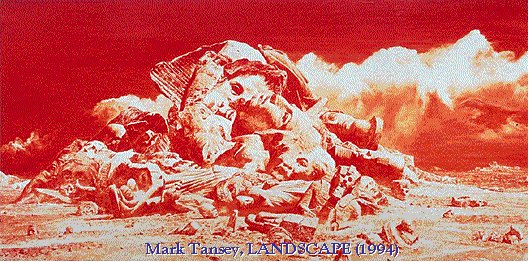

Over the past few centuries humanity has witnessed the most dramatic and rapid cultural transformations ever known. So great, in fact, has this rate become that each generation now alive absorbs within its lifetime an amount of technological and social change that traditionally occurred over the course of many centuries. What are the social and psychological implications of such rapid rate of social change? How does it affect our orientations to the past and to the future?

The nature of collective memory and the processes of historical revisionism

have intrigued me for some time. For instance, consider the proposition

that it is at the age of nine when a public event creates a lasting impression

on a person's memory. If this be the case then in 1998:

The nature of collective memory and the processes of historical revisionism

have intrigued me for some time. For instance, consider the proposition

that it is at the age of nine when a public event creates a lasting impression

on a person's memory. If this be the case then in 1998:

A sampling of research topics:

How did Davy Crockett die at the Alamo--and who cares? And what

motivated 189 men to take on over one thousand trained troops of Santa

Anna's? One historian claims the motive was not one of patriotism nor

principle but rather greed: they were fighting for the loot that David Bowie

had brought into the compound from the fabled San Saba treasure.

How did Davy Crockett die at the Alamo--and who cares? And what

motivated 189 men to take on over one thousand trained troops of Santa

Anna's? One historian claims the motive was not one of patriotism nor

principle but rather greed: they were fighting for the loot that David Bowie

had brought into the compound from the fabled San Saba treasure.Some Web sites capturing this idea:

Through their museums, monuments, historic districts, and street names,

cities commemorate their heroes and preserve memories of their collective

pasts. Of the urban renewal campaigns of the immediate postwar era, Spiro

Kostof observed (in PBS's "America By Design: Public Places and Monuments,"

Fall, 1987):

Through their museums, monuments, historic districts, and street names,

cities commemorate their heroes and preserve memories of their collective

pasts. Of the urban renewal campaigns of the immediate postwar era, Spiro

Kostof observed (in PBS's "America By Design: Public Places and Monuments,"

Fall, 1987):

Destroyed were old buildings which told us who we are, what we've been through, what we are apprised or allowed. They are a tangible record of our existence as a people. We erase that record bit by bit, and in so doing we deny ourselves the comfort of our collective past. We Americans have been enthusiastic destroyers. Our new towers deny tradition. There are no story-telling declarations. ...Most of us demand sign posts that remind us where we came from and that lead us toward our identity.Currently, historic preservations are on the rebound. As cities become indistinguishable with their malls and national franchises, it is their pasts that make them unique.

Just as individuals need a sense of order in their biographical experiences, there are both personal and social needs for individuals to transcend their own lives and to understand their own biographies within the context of those of their ancestors and successors. The experience of community, for instance, has a retrospective aspect, involving "a tradition carried from generation to generation...[wherein] the living acknowledge the work of the dead as living on in themselves forever" (Michels, 1949:160). Then there's the prospective aspect, described by Bertrand Russell as "making part of one's life part of the whole stream and not a mere stagnant puddle without any overflow into the future." The symbolic representations of such continuity are deeply woven into the fabric of religious symbolism (Bellah, 1964), inculcating a trust in the continuities of life, of one's people, of one's works for others, and allowing one to see them comprising a long chain of meaningful being.

One way humans have attempted to participate in this sacred time

is by replicating the activities of their ancestors. What is sacred is

the order that links our activities with an overarching meaning. Sacred

time is the collapse of the past and future into an eternal now so that

the heroics of our ancestors and our descendants are forever part of the

present. To accurately repeat the rituals of one's ancestors, as in a traditional

ceremonial dance, is to participate in sacred time. In this sense, the

expeditions of Thor Heyerdohl and the duplication of the voyages of the

Godspeed (the ship carrying tradesmen and farmers to Jamestown in 1607)

and the Mayflower, while being scientific and historical enterprises, may

also be religious rituals.

One way humans have attempted to participate in this sacred time

is by replicating the activities of their ancestors. What is sacred is

the order that links our activities with an overarching meaning. Sacred

time is the collapse of the past and future into an eternal now so that

the heroics of our ancestors and our descendants are forever part of the

present. To accurately repeat the rituals of one's ancestors, as in a traditional

ceremonial dance, is to participate in sacred time. In this sense, the

expeditions of Thor Heyerdohl and the duplication of the voyages of the

Godspeed (the ship carrying tradesmen and farmers to Jamestown in 1607)

and the Mayflower, while being scientific and historical enterprises, may

also be religious rituals.

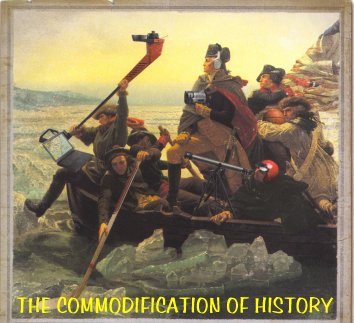

It seems as though retro

has become the leit motif of popular culture in the 1990s. In 1992

there appeared in my mailbox the Pastimes catalogue featuring fifties-style

bikes, models of autos from the 1920s on, models of WW II aircraft, Roman

numeral clocks, Civil War vessels, sailing vessels in bottles, paper models

of Wrigley Field, quilt designs, and Victorian rocking horses. "Adult rock"--e.g.,

the moldy oldies--fills the radio spectrum. The proliferation of "Classic"

labels: Classic Coke, Classic Rock, Classic Dinners, Classic baseball fields,

etc. Of the shows opening on Broadway in 1995, fully one-half were revivals.

Television shows of the fifties and sixties have become big screen movies

in the nineties. Have you wondered what is going on? Among the suspected

forces:

It seems as though retro

has become the leit motif of popular culture in the 1990s. In 1992

there appeared in my mailbox the Pastimes catalogue featuring fifties-style

bikes, models of autos from the 1920s on, models of WW II aircraft, Roman

numeral clocks, Civil War vessels, sailing vessels in bottles, paper models

of Wrigley Field, quilt designs, and Victorian rocking horses. "Adult rock"--e.g.,

the moldy oldies--fills the radio spectrum. The proliferation of "Classic"

labels: Classic Coke, Classic Rock, Classic Dinners, Classic baseball fields,

etc. Of the shows opening on Broadway in 1995, fully one-half were revivals.

Television shows of the fifties and sixties have become big screen movies

in the nineties. Have you wondered what is going on? Among the suspected

forces:

Internet scholars refer to accelerating change as technological singularity. As described at Singularity Watch, "Some 20 to 140 years from now—depending on which evolutionary or systems theorist, computer scientist, technology studies scholar, or futurist you happen to agree with—the rate of self-catalyzing, self-organizing, ever more autonomous (human-independent) technological change in our local environment will undergo a "singularity," becoming effectively instantaneous from the perspective of current biological humanity."

On the other hand, there are claims that post-boomer generations have been change-deprived. The speed of commercial air travel, for instance, has not increased since at least the 1970s--and probably has declined if one takes into account the delays in take-offs and landings. It's been a quarter century since we've seen the 80 mph speed limit on the Kansas Turnpike. What recently compares with the collective transition from radio to television, or from the black and white sets to the color ones introduced in the 1950s? Cancer rates are higher now than they were one-half century ago. In "The Slowing Pace of Progress" (U.S News & World Report, Dec. 25, 2000), Phillip Longman argues how much greater change was in the first versus second half of the twentieth century

Perhaps never has it been more imperative to expand our future horizons and to consider the long-term ramifications of our current collective activities. The twentieth century needed its Henry Fords but it also could have used individuals with the foresight to consider the ramifications of tens of millions of vehicles: the paving of America, gridlock, suburbanization, the politics and economics of fossil fuels, and global warming. There are forces working against such thinking, such as capitalism's attention to short-term profits and the need for quick results for those facing reelection every two-years in the House of Representatives. One group seeking to counter such trends is the Long Now Foundation, which "hopes to provide counterpoint to today's `faster/cheaper' mind set and promote `slower/better' thinking. We hope to creatively foster responsibility in the framework of the next 10,000 years."

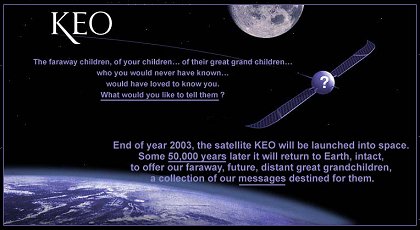

Not only do we seek connections with generations past but also with

generations yet to be born. Below an

Oglethorpe University building is the "Crypt of Civilization," a

swimming pool-sized time capsule constructed in 1940--the brainchild of

Thornwell Jacobs,

who viewed it our "archaeological duty" to preserve cultural artifacts for six

thousand years. When opened in the

year 8113, there will be for future archaeologists hundreds of thousands of

microfilmed pages of literature and science, a quart of beer, the contents of a

woman's purse, and a Donald Duck doll. The Westinghouse Time Capsule from the

1939 World's Fair in

Flushing Meadows, N.Y., is to be excavated in 6939. Want

to leave your own? Purchase one from Future

Archaeology.

Not only do we seek connections with generations past but also with

generations yet to be born. Below an

Oglethorpe University building is the "Crypt of Civilization," a

swimming pool-sized time capsule constructed in 1940--the brainchild of

Thornwell Jacobs,

who viewed it our "archaeological duty" to preserve cultural artifacts for six

thousand years. When opened in the

year 8113, there will be for future archaeologists hundreds of thousands of

microfilmed pages of literature and science, a quart of beer, the contents of a

woman's purse, and a Donald Duck doll. The Westinghouse Time Capsule from the

1939 World's Fair in

Flushing Meadows, N.Y., is to be excavated in 6939. Want

to leave your own? Purchase one from Future

Archaeology.

If men could foresee the future, they would still behave as they do now. --Russian Proverb

The ability to predict what is going to happen (and, ideally, when and

where), to anticipate challenges to one's intended goals, is the core strategy

of human endeavors. From the divining from sheep entrails to the readings

of computer-generated weather forecast simulations, humans have always

attempted to plan for (and hence be able to affect the course of) future

events. Of course, acting on such predictions has led to self-fulfilling

prophecies and to unintended consequences.

The ability to predict what is going to happen (and, ideally, when and

where), to anticipate challenges to one's intended goals, is the core strategy

of human endeavors. From the divining from sheep entrails to the readings

of computer-generated weather forecast simulations, humans have always

attempted to plan for (and hence be able to affect the course of) future

events. Of course, acting on such predictions has led to self-fulfilling

prophecies and to unintended consequences.When you think about it, an impressive portion of the labor force is involved in the business of futurology. There are, for instance, the:

With the conclusion of the Twentieth Century, it is fascinating to compare life now with what was prophesized by such writers as Edward Bellamy and H.G. Wells. Many are so off the mark that they have become subjects of humor. What faulty assumptions or unexpected developments account for the predictions which failed? What principles of historical processes permitted accurate extrapolations of the future?